The Egyptian identity has gone through many phases. From the times of Ancient Egypt to the influence of the Christian Coptic and Islamic civilisations, the question of what constitutes as ‘Egyptian’ is still very confusing.

Egyptian dance, for instance, is often attributed to whirling dervishes, stick-fighting, and belly dance. It is not so common that one hears of famous ballet dancers as they do in Moscow or Paris. Yet in the 1950s and 60s, the ballet industry faced its first boom with the rise of Soviet influence and the vast cultural revolution that was taking place at the time.

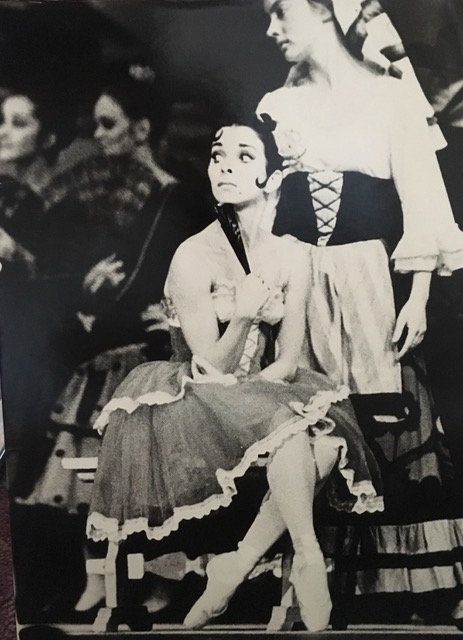

In the midst of all of this, Egypt saw the birth and growth of its first ever prima ballerina: Magda Saleh.

This ballerina’s story was at the heart of all the dramatic changes that occurred in Egypt, from the decline of British influence, to the 1952 revolution and finally to the 1973 October War, all of which had a tremendous impact on her ballet career.

“It was very difficult to pursue this dream, and I credit my parents for supporting me all the way through,” Saleh says to Egyptian Streets, “I was also studying English Literature at Ain Shams University beside my dancing, so it required a lot of hard work and determination, but I was very fortunate that my parents encouraged me.”

Born to a Scottish father and an Egyptian mother, Saleh was first taught ballet by British instructors during Egypt’s monarchical period. Yet after the events of the 1952 revolution and Egypt’s transition from a monarchy to a republic, her ballet career began to take on a whole new path.

The new Minister of Culture Tharwat Okasha created an Academy of Arts with a Higher Institute of Ballet in 1959, which he envisioned to be the ‘cornerstone’ of the new ministry to educate and produce artists and professionals.

“He was one of Egypt’s great sons,” Saleh says, “the ministry of culture today is what it is because of him. He cast a very long shadow, and that’s because he had a vision and he planned for the future.”

In 1963, five students from the institute were offered scholarships to study at the Bolshoi Ballet company, and when they returned, the Cairo Ballet Company produced its first ballet written by Boris Asafiev, Fountain of Bakhchisarai.

The first experience for the ballet company was astounding – a “meteoric rise” as Saleh states, to the point that for the first time in Egypt’s history, President Gamal Abdel Nasser awarded the dancers the Order of Merit.

“All of the dancers were Egyptian, and the only professionals were just me and my other colleagues,” she adds, “today, the Cairo Ballet hires a lot of foreign dancers, and I am not sure why, since they should be producing more national dancers.”

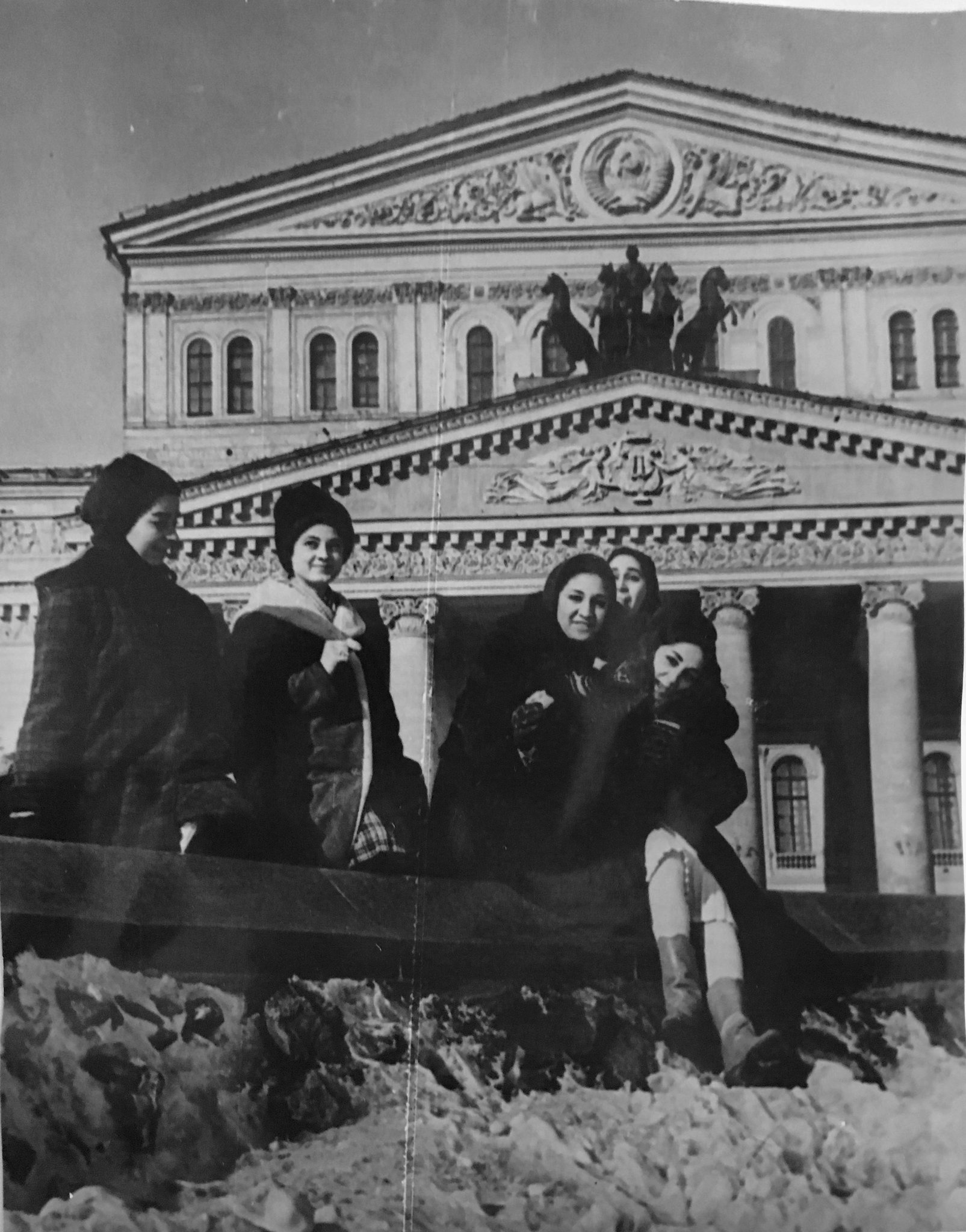

As more shows followed, Saleh went on to reach the peak of her success to become Egypt’s first prima ballerina. The unprecedented event came when she was invited by the Soviet Ministry of Culture to tour the Soviet Union with her partner Abdel Moneim Kamel, where she performed as a guest artist with the Bolshoi Ballet in Moscow and the Kirov Ballet in Leningrad.

Yet once again, Egypt started to face new challenges and switch paths. The Russians were now packing their bags to return home, as President Sadat decided to expel the Soviet advisors in 1970s and cut ties with the Soviet Union.

A year earlier, the Royal Opera House in Cairo was burned down, which left little hope for the dance industry to revive again.

As many of her dance colleagues went to continue their dance career in Russia and Europe, Saleh left to the United States to receive a master’s degree in modern dance at the University of California and a doctorate from the New York University.

In 1983, she returned to Cairo as a dean at the Higher Institute of Ballet and then as the new founding director of the New Cairo Opera House, which was successfully reopened in 1988. Currently, she resides in New York with her husband Egyptologist Jack Josephson.

“Given the current upheavals, I think it’s a miracle that it (the Higher Institute of Ballet) still exists, as there is currently a struggle between two opposing forces over Egypt’s soul,” Saleh notes.

“There is a quote from a friend of mine who passed away recently, the Egyptian American composer Halim El Dabh. He said ‘if you scratch an Egyptian, you will find an ancient Egyptian’, which means that we have a core deep down with us that relates to our ancient history, and I hope he’s right, because it means we can still survive despite the challenges.”

Today, this core is still swimming in Egypt’s streets, with the rise of the new popular page ‘Ballerinas of Cairo‘, reminding Egyptians and young dancers that the future of Egypt’s artistic voice is still very much alive.

Comments (5)

[…] started ballet from a young age and led a successful career as a dancer and patron of the arts, receiving many opportunities and honors over the decades. She remained active and involved in the […]

[…] ٩ أكتوبر ٢٠١٨ كتبت : ايجيبشن ستريتس – ترجمة: رحمة […]