On the occasion of the anniversary of the birth of Prophet Muhammed, it is necessary for Muslims in Egypt and around the world to take the opportunity to reread the works of old Islamic scholars and intellectuals that, though are rarely discussed, still can contribute to the attempts of reforming religious discourse today.

Before it was overcome by tribal fanaticism and fervent pursuit of political power, Islam emerged as a rational humanitarian call that allowed the poor and the marginalised to join and reach out to a God that restored their humanity. Throughout the Quran, the feeding and protection of orphans, the poor, and the needy are seen as the main articles of faith that indicate one’s true devotion to the teachings of Islam.

However, these primary values have been overshadowed by various political and tribal conflicts that changed the course of Islamic history. Currently, it is has become more important than ever to return back to the roots and trace the different ideas in Islamic thought over time.

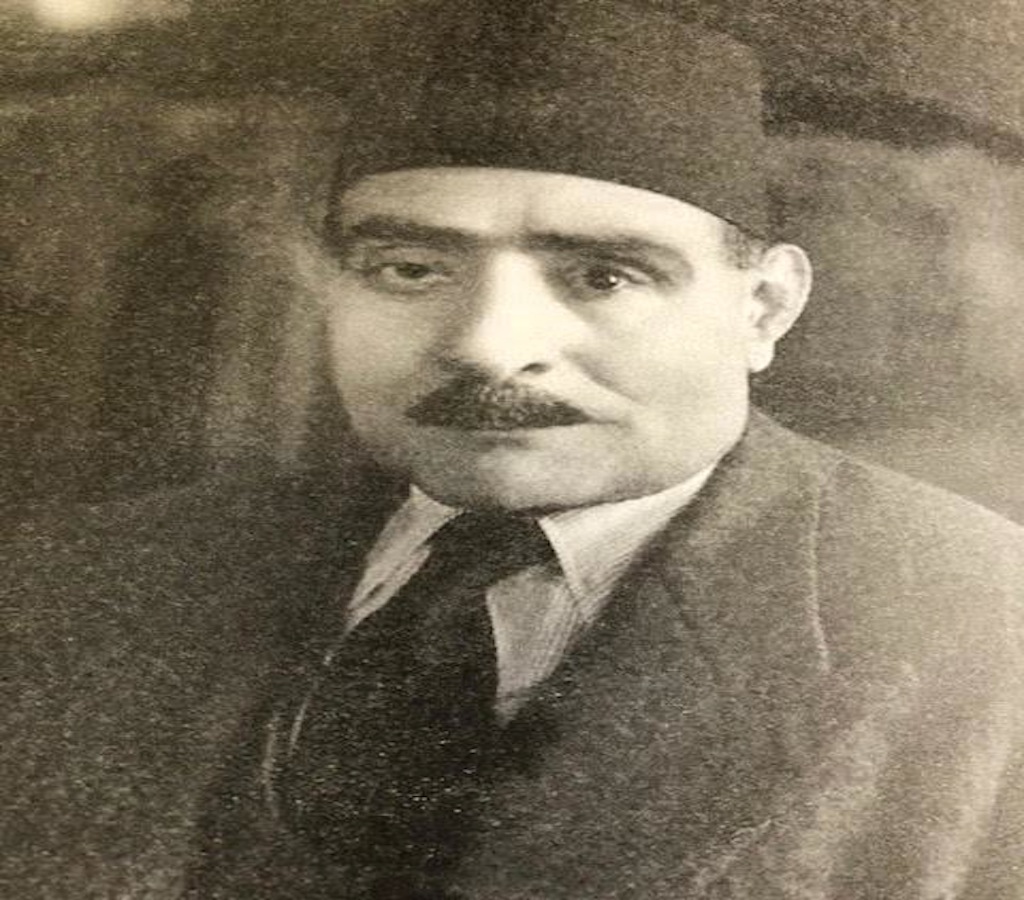

While the ideas of Sayyid Qutb are widely known and popular, there was another Islamic thinker that was writing around the same time: Ali Abd al-Razik.

Ali Abd al-Razik was an Egyptian scholar of Islam, religious judge and government minister. His 1925 book ‘Islam and the Foundations of Governance’ caused him a lot of trouble after a committee of Islamic scholars pressed charges against him for “insulting” Islam and the early Caliphs, stripping him of the prestigious title of a “Alim” (learned scholar).

What Abd al-Razik argued in his book, however, was simply this: that nowhere in the Qu’ran or the Hadith was the Caliphate mandated or even recommended. The previous year before the book’s publication, the Ottoman Caliphate had just been abolished, and many Muslim intellectuals debated intensively about new ways to establish a caliphate.

As Madawi Al-Rasheed states in his book ‘“Introduction: The Caliphate: Nostalgic Memory and Contemporary Visions”, the caliphate mattered to Muslims immediately after its downfall because of what it represented: unity, strength,and glory for Muslims. It became to function as a beacon of hope, “within which all grievances are resolved, and all aspirations are fulfilled”.

Yet for Abd al-Razik, the caliphate should not hold this significance in Islam. Using Meccan verses from the Quran, al-Raziq presented Prophet Muhammad as a religious leader concerned only with spiritual salvation of his community.

He distinguished between his religious duties and political duties, and argues that though there were political events that influenced his activities, Prophet Muhammad was first most a religious leader with a religious call.

He uses the example of other prophets, such as Moses, who also had political duties along with his religious duty.

To prove his point, Abd Al Razik adds that if the caliphate was certainly a religious duty, then the Prophet would have indeed appointed a successor. However, this was not the case, as the caliphate arose merely as a political necessity for the rightly guided caliphs (Rashidun) to affirm their rule.

He is quoted to have said: “Islam did not determine a specific regime nor did it impose on the Muslims a particular system according to the requirements of which they must be governed; rather it has allowed us absolute freedom to organise the state in accordance with the intellectual, social and economic conditions in which we are found, taking into consideration our social development and the requirements of the times.”

Moreover, according to Abd al-Razik, there are verses in the Quran which enjoin Muslims to obey God, the Prophet and the “holders of authority” (ulu’ l-amr), but definition of the term’ authority’ is left vague.

He argued that past rulers spread the notion of a caliphate to use “religion as a shield protecting their thrones against the attacks of rebels.”

There has been a clear imbalance in Islamic thought over which ideas become more widespread and common and which do not, and to ensure that Muslims do indeed become “united”, as advocates of the caliphate aspire to achieve, then this unity must first be attained by giving intellectual freedom and equality to all Muslim writers and thinkers.

Such is the kind of unity that will provide real strength and glory for the entire Muslim world.

Comments (0)