Artist and Associate Professor of Graphic Design at Virginia Commonwealth University in Qatar, Basma Hamdy curates a treasure of a volume that highlights and contextualizes Noha Zayed’s astounding photography by chapterizing it and punctuating it with brilliant essays and interviews around Arabic typography. Creative entrepreneur and artist, Noha Zayed’s personal Instagram account as well as the popular arabictypography account that she co-curates “cataloging Arabic lettering from all corners of the world” are often cited in lists of the best photography accounts from Egypt.

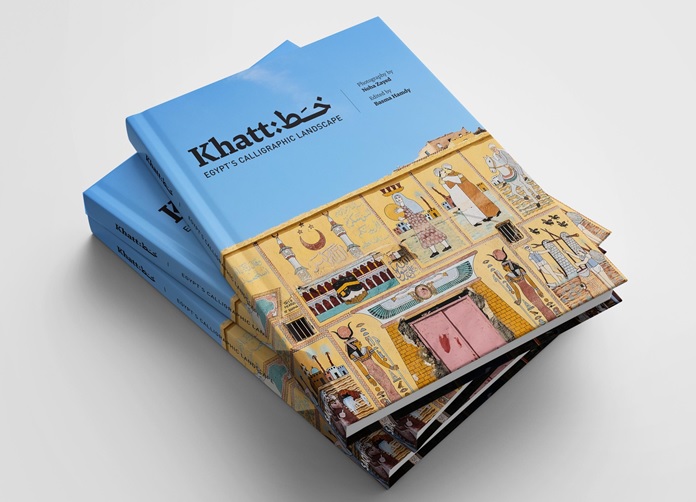

Yasmine Motawy, talks to Noha Zayed about the book on the eve of the opening and book launch of Khatt: Egypt’s Calligraphic Landscape at Kodak Passageway, The exhibition runs from the 19th to the 28th of December.

The decision to contextualize the photograph does change things, because in your Instagram account, a lot of the photographs gain some of their impact from being immediate and de-contextualized, unexplained, with scarce hashtag to explain the bizarre circumstances or fortuitous location you happened upon. Did this concern you at all?

As I am self taught at photography and many of the other things I do, I spend a lot of time experimenting and refining my form and content, so even my approach to disseminating and reproducing my work is evolving. Like most people, I have a complicated relationship with social media depending on where I am in my life.

My father would have parties where he would bring out his slide projector and narrate the photos he took to our guests, and I guess this kind of display reel is what I found in Instagram. As a photographer, when Instagram first came out, it was the best available social media platform for me; I did not want to be branded or to say too much about myself or about the photographs. On Instagram, I sometimes struggled with not answering people when they posted questions asking for more details or information about a photograph, I did not always feel that information could be properly cushioned in an Instagram post. The bigger a following my account had, the more I received requests to turn myself into a brand, but I really wanted people to focus on the photography itself rather than on my persona.

While I was comfortable using Instagram as an outlet, I struggled with the meaning of what I was doing, and this led to the book project, a new space where I resolved my struggle with meaning by filling the gaps that social media left. With the book, I felt I had curated the photographs into something more useful. I value books, and always felt that arranging and solidifying the photos into a book would be a second act of creation.

I have had the privilege of seeing you take stunning photographs using your iPhone. The democratization of the form you are using, and the fact that every nook and cranny of Egypt has been photographed and disseminated must make it particularly special that your talent as a photographer of Egypt has been recognized? Have you collaborated with other photographers? How has that unfolded?

I go on weekly Friday excursions to take photographs with photographer friends and have done so regularly for the past 2 years. There is a fixed trio of us and sometimes other photographers will join us, it has been a very informal relaxed collaboration so far.

When I first started, I mostly took photos with an iPhone and used my Nikon camera when I was travelling. As I became more serious about photography I made the switch, and I now mainly use fujifilm and Canon cameras.

As for all the photographs out there, I often get the opportunity to go where others do not go, and I recognize that photographers are motivated by different things, and so I am not too worried about the photographs being part of the flood. Yes, I think it all comes back to deliberateness and motivation, so for instance, when I am in Upper Egypt taking photos, I am truly appreciative and interested in what is before me, I am not thinking of the photo I am taking as ‘A Photo from Egypt’ or a media/tourism shot or a statement on the country. To retain the integrity of some of the photos that might fall under this category, I often refrain from captioning many of them.

In fact, oftentimes when I plan to photograph something specific, I usually fail in a big way, it is only after I take photos and spread them out that they make sense. I snap up a lot of my photos on the fly, I am a quick photographer which I think is a leftover legacy from my iPhone days.

I grew up addicted to the written word, reading the back of cereal boxes and medicine pamphlets, and like you, I believe the right book or message arrives when you need to be reminded of something; your eye clearly gravitates towards the written word as well, how prepared are you to capture the moving text on the backs of trucks that you talk about in the essay “Trucks: A Moving Canvas”?

On the road, an iPhone and a clean windshield! I sometimes change direction and take an exit to chase a truck down. I took an advanced driving course when I lived in Libya, but I still think it is pretty dangerous, don’t do it.

In chapter two, “Text Sells,” the contemporary street signage you capture evokes an eerie sense of nostalgia for what still exists but is likely to disappear soon. This evokes greater discussions on the change in the cityscape as older quarters are overlooked and new satellite cities receive attention and investments. What part does this sense of loss play in your photography and documentation?

Although this books is about calligraphy, it is still personal; loss figures greatly in my personal life so I guess that is reflected in my ways of seeing. I am also a collector of objects and my memory is assisted by photographs. I am interested in constant documentation, I see how villages change every time I visit, a sign replacing another, a peeling wall repainted differently, I sometimes meet trucks that I have photographed at other times on other roads, and these encounters tug at me.

I have also gone to places that were on the brink of disappearance or dramatic change. For example, I had the chance to visit an area in the Sudan before it was submerged in water because of the building of a dam, as well as geographical locations I had read about when I was a child. Sometimes I feel I am racing against time to capture things before they change or disappear. Maybe that is why I photograph fast.

The final chapter five, “Manifested Glory,” humanizes religious invocations by contextualizing them in the urban spaces they, as well as the city’s devout, cannot escape. In fact, a lot of your work locates the elevated, the human, and the Beautiful in the midst of distractions and visual clutter. The photograph you selected for the exhibition poster also juxtaposes the sacred and the profane. Is this part of a deliberate aesthetic?

I find it very interesting that people tell me that my photos show them beauty in the midst of ugliness, because they are often referring to the very photos I have taken when I have been at the depths of despair and unhappiness. Anyway, in Egypt, one constantly has to deal with all this awe-inspiring grandeur on one hand, and the grotesque mundane on another. In hindsight, these photographs that people see as positive are probably my attempts to locate humor and make sense of it all.

What are we going to see next from you?

The question I get the most is “what is it that you do?” and I know that I am fortunate in that what I do takes me to the places where I want to be. I like to have range and along the same thread of documentation, I am making a lot of audio recordings these days, a couple of photography projects, working on the family banana farm and trying to figure out what to do with my life.

Comment (1)

[…] Source link […]