It is much easier to perceive a supposed ‘enemy’ or a problem within the boundaries of the present time. When right-wing parties in Europe look at Islamist terrorism and immigrants, they look at such issues through a narrow context that only includes certain actors and events, such as 9/11 and the recent terrorist attacks, and exclude the historical and political narrative behind it all.

Similarly, in the Muslim world, there are certain problems that are often looked at without its historical context – and that’s the problem between Sunnis and Shi’is. In every conflict that exists in the Middle East, the issue of sectarianism is always used as a lens for explanation.

In Yemen, for instance, it is seen as a Saudi-led coalition launched a war against the Zaydi Shiite armed group known as the Houthis. In Syria, the war has also often been portrayed as a sectarian conflict between a Sunni majority population and a minority Shiite ruling elite. ISIS have also carried out one of the most ruthless genocides against Shi’is in Iraq and Syria, as the terrorist organization’s magazine Dabiq features 14 pages justifying violence against modern day Shi’is.

Even more broadly, the Saudi government’s regional competition with Shiite-majority Iran has fueled fears of a wide scale religious war in the region, or a ‘third world war’. The regional rivalry, which includes proxy wars in almost every conflict in the region, has been compared to the events that predated the Thirty Years’ War in Europe, in which a battle among Catholic and Protestant states developed from a religious to a large political conflict.

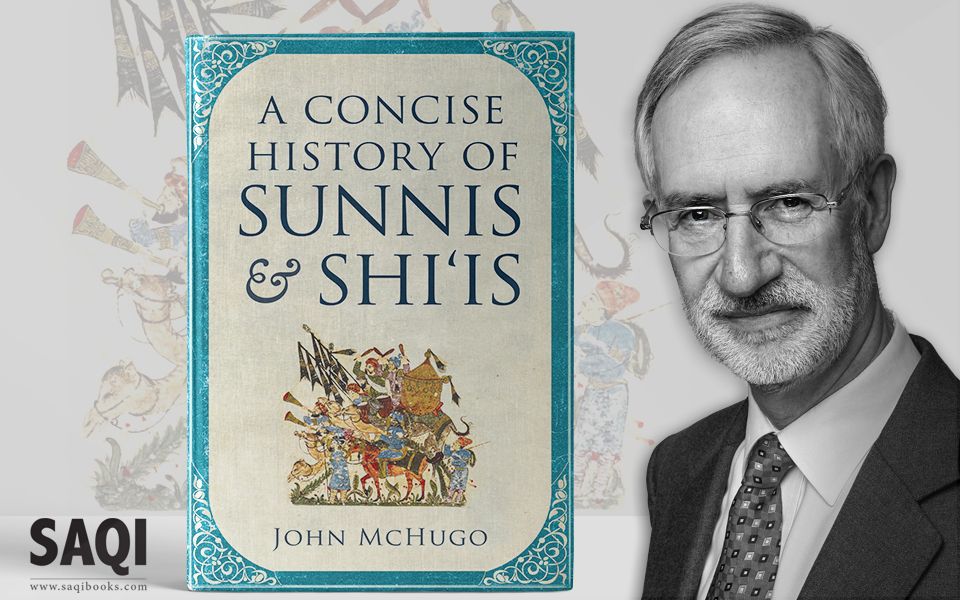

Yet John McHugo, in ‘A Concise History of Sunnis and Shi’is’ published by Saqi Books, takes a different approach. Rather than labeling the conflicts in the Middle East as simply a Sunni-Shi’i divide, McHugo argues that the bloodshed in the region is mostly due to political issues that have expanded across history.

It is not through an ‘Arab NATO’ alliance against Iran, which US President Trump is working on to develop with Arab leaders, that will help stop the violence and fighting, but by solving the political problems that contributed in fueling these wars today.

Covering over 1400 years of Islamic history, with all of its complexity and various interpretations, is quite a challenge – yet McHugo accomplishes it superbly. The history is clearly divided into two parts: from the early times of Islam and Prophet Muhammed, to the period of colonialism and the current modern time. He provides a fresh interpretation that is not often acknowledged by some Arab scholars, which tend to gloss over the Shi’a interpretation and exclude it from the narrative. Throughout the book, however, McHugo bravely takes on different interpretations that provide the book with an extra element of richness and balanced analysis, connecting the two – Sunnis and Shi’is – together rather than further separating them apart.

Instead of seeing a literal divide between Sunnism and Shi’ism, McHugo points out that both have always been interlinked across history. The meaning of ‘sect’ in Christian theology, which thinks of a religious grouping that completely split off from the mainstream ideas, is not applicable to meaning of sect in Islam. The split between Sunnis and Shi’is mainly arose out of an ancient dispute concerning who should exercise religious authority among Muslims, yet such divide was never given as much notice or attention until today. Currently, this ancient dispute is used as a weapon by political figures in the West to simplify the political issues in the region and, as such, lead them to propose policies that only increase their power and authority in the region.

In the second part of the book, McHugo tackles an important part of history that is also often excluded from analysis, and that is the period of Western colonialism, nationalism and the Islamist reaction that arose from these events. This is the heart of the book, as McHugo presents more clearly his analysis of the events and how it culminated to the Sunni-Shi’i divide today, compared to the more descriptive approach used in the first part. Flawed state formation in the Middle East, the ideology of Wahhabism and other Islamist movements which spread anti-Shi’ite rhetoric and the manipulation of religion by powerful states to maintain hegemony all contributed equally to the present violent conflicts.

While the book doesn’t tackle the possible changes that are ongoing in Saudi Arabia, whether it still binds with its old state ideology or is learning to evolve, it still provides an important starting point of analysis for other scholars to follow, which is by looking at how the nineteenth century and onwards played an incredibly important role in the Sunni-Shi’i divide in contrast to an ancient dispute in early Islam.

In a time where problems seem too complex to be fully digested and understood, John McHugo dives into this web of complexity and comes out with a clear, concise and accurate picture of how events today should be perceived. Such perception should provide more comprehensive solutions and policies that include the historical and political context and address the key roots of the conflicts.

Egyptian Streets recommends this read.

Comment (1)

[…] Source link […]