Mariam Bahaa, Architecture student at the American University in Cairo, recounts her hate for her native Arabic language, mainly enforced by national curriculums taught in schools. Arabic lessons during Thanaweya amma were four hours of torture, for Bahaa.

Her appreciation for the language was fostered after graduating from school, however, it was too late as now she can neither read nor write proper Arabic. She became a linguistically handicapped Egyptian.

In the past few years, the foreign languages craze has been increasing among Egyptians. People are becoming more and more encouraged to master languages like English, French, and German; while neglecting and belittling their native Arabic or Egyptian language.

English, especially, is becoming more and more integrated in the Egyptian life. People are using it to converse, seeking it for education, and preferring mass media that integrates or uses English as their main language; which undermines the position of the natives’ language. For Egyptians, Arabic proficiency is on an ongoing deterioration.

Some people even think it is “cool” as Maggie Talaat, an Integrated Marketing Communication student at the American University in Cairo states, “to brag about how weak our Arabic is, and it’s in fact not that cool. Most of the students at AUC have been raised and are now living in Egypt, so it does not make sense when they can’t speak or write proper Arabic.”

Education plays a significant role in shaping individuals; and recently, international education and the variety of foreign syllabuses provided to the Egyptian public have drastically marginalized Arabic language. Yasmine Rashad, an Accounting major at the American University in Cairo, tells her experience as a student at the prestigious International School of Shoueifat.

She states that everything was taught in English except for Arabic, Religion, and in some years they also had social studies. “All of us, however, used to think that these subjects were useless and no one took any of these seriously. Arabic especially, since we had to take it in all of our academic years; and religion, obviously, but no one really cared about its exams as much as Arabic because we all felt that Arabic lessons were much harder.

Still, no one gave it that much attention, as before the exams they would give us a sheet that we technically memorize and the exam comes exactly as per the sheet.” In addition, it is important to note that Rashad emphasized the fact that her school was “academically rigorous” where the concept of memorizing was not at all common; except for the Arabic lessons or courses.

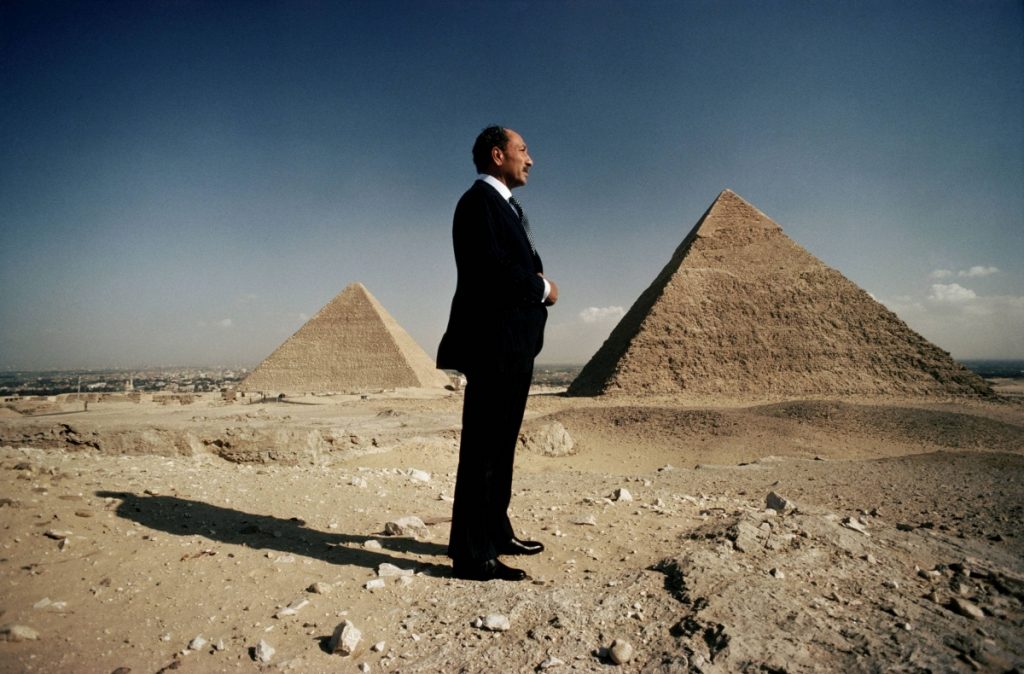

Prestige is not the only reason why parents, nowadays, encourage their children to pursue foreign education. President Anwar El Sadat’s policy of “infitah” or “opening doors” which followed the 1973 October war, opened doors for both domestic and foreign investment in private sector; and with the process of globalization, the job market has become more and more competitive.

International institutions usually require candidates who are relatively proficient in a foreign language to enable them to communicate; however, Mona Hassan, linguistic professor at The American University in Cairo, asserts that “we cannot deny that some students graduating from international schools admit that in some international institutions or companies, it is a privilege to be fluent in the mother tongue in addition to the foreign language.”

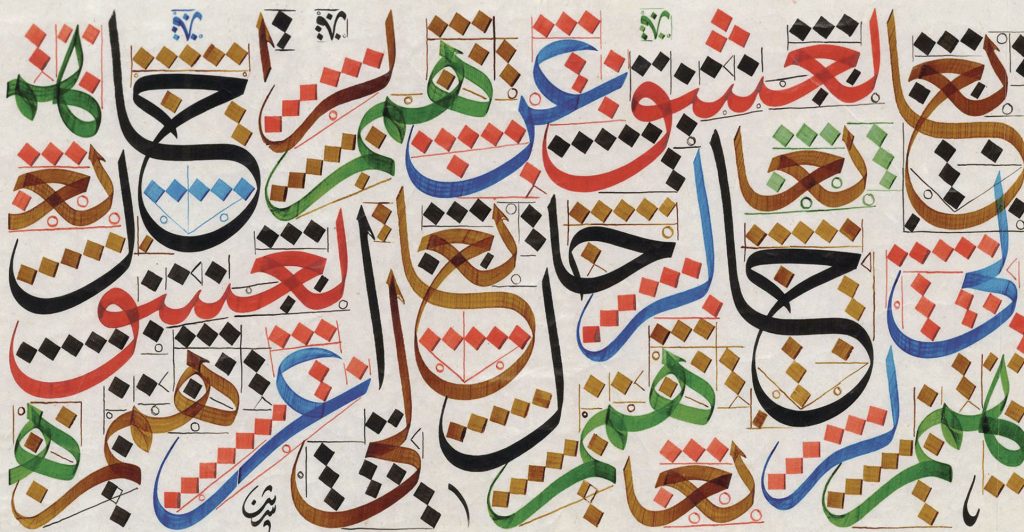

Interestingly, foreigners can spend lots of effort, money, and time in order to get a hold of the Arabic language, for example, some take up Arabic lessons in an attempt to learn the language. Some succeed at learning at least to speak; while others confess it is really hard to acquire such language.

While foreigners seek Arabic knowledge, natives don’t. This, according to Hassan, “reflects the image of a community which does not show respect to the Arabic language.”

The invention and widespread of the relatively new Franco-Arabic writing which includes the usage of English letters to write in Arabic, reflects the ease and familiarity of young people with English alphabet rather than the Arabic alphabet. “It is a shame … [as people] in most Western countries [are] very proud of their mother tongue. They learn foreign languages just to meet the outside world’s requirements, diplomatic needs, marketing needs, and commercial needs.”

The importance or significance of being bilingual or trilingual is undoubted. In fact, being fluent and proficient in one’s own native language can be regarded as a golden opportunity to learn and acquire a skill.

Rashad affirms that despite being more comfortable and confident in reading, writing, and expressing in English, she is unlikely to perfect her acquired English linguistic.

This is by virtue of being an Egyptian and mainly exposed to Egyptian vocabulary more than an English one. The frustration of not being able to properly attain any of the languages appropriately leaves questions of whether can she ever become a native speaker of any language at all.

The invasive English phenomenon is not only restricted to Egypt. According to the Arab Youth Survey 2015 that was released in Dubai recently, 36% of young Arabs use English as a language communication tool instead of Arabic on a daily basis; and the number have not decreased since then.

A later survey, published in 2017, finds that “despite their pride in the Arabic language, most youthful Arabs say they are using English more in their daily lives.” Many young individuals now find English to be more convenient to them when either talking or writing.

The benefits of an international education are undeniable, however, it also raises questions about its negative effects. Egyptian youths, now, have more access to foreign media, whether it is music, movies, or TV series, and almost everything can be easily accessed through the internet.

Western languages are becoming invasive as Egyptians are attracted to foreign productions, which eventually influence their perceptions and ideals. The Arabic language reflects the Egyptian culture, and younger generations need to be aware of the value of their native language, as well as the importance of its proper practice as a mean of preserving their Egyptian heritage.

Comments (2)

[…] of shame is not limited to Egypt. In the Arab Youth Survey published in 2015, it was found that 36 percent of the younger Arab natives in Dubai speak English rather than their mother tongue in their […]

[…] Arabic for Egyptian Youth: a Forgotten Privilege […]