A while back, I stumbled across a digital illustration on social media which read “English is a language, not a way to measure someone’s intelligence.”

The meme resonated with me. It spoke to a phenomenon that happens across the Arab world and particularly in Egypt where a native’s level of proficiency in English — or whatever second language they speak — has become a measure of their worth and an indicator of their socio-economic class.

Many Egyptians have refined and perfected their English, at times to the detriment of their mother tongue, which they have lost due to a lack of practice, or rather due to the disproportionate weight placed on speaking a foreign language.

An individual with advanced skills in the Arabic language — considered one of the hardest to learn for English-speakers — and a beginner’s level English is perceived differently socially from the individual with advanced English and beginner’s Arabic.

This concept permeates many aspects of society in Egypt where entry to several bars and clubs around the capital hinge upon one’s level of spoken English, which is used to gauge patrons’ education and socio-economic class. If the person’s accent is to the liking of the door selector, then they are immediately granted access. If it is not, they are denied access.

The degree to which an individual’s accent is imbued with a western inflection is directly proportional to the degree to which their peers will admire them — the English language therefore becomes a tool to measure one’s intelligence and socio-economic class in Egypt.

However, the language considered the international language of science for centuries was, at one point in time, Arabic. This was due to the advancements brought on by Arabs during Islam’s golden age — the effects of which are still felt to this day.

This obsession with speaking a language that is not our own to perfection while neglecting our mother tongue is not exclusive to Egypt. It has spread across the region with the exception of a few countries.

This infatuation with the West as superior has proliferated in many aspects of our lives, overtly in some cases, and inconspicuously in others. Though it is not always said outright, it can be felt in the conversations when comparing the West to the Arab world.

Egyptians even have a term for this mentality that has become pervasive in the country: 3o2det El Khawaga (the complex of the foreigner).

The International Language of Science

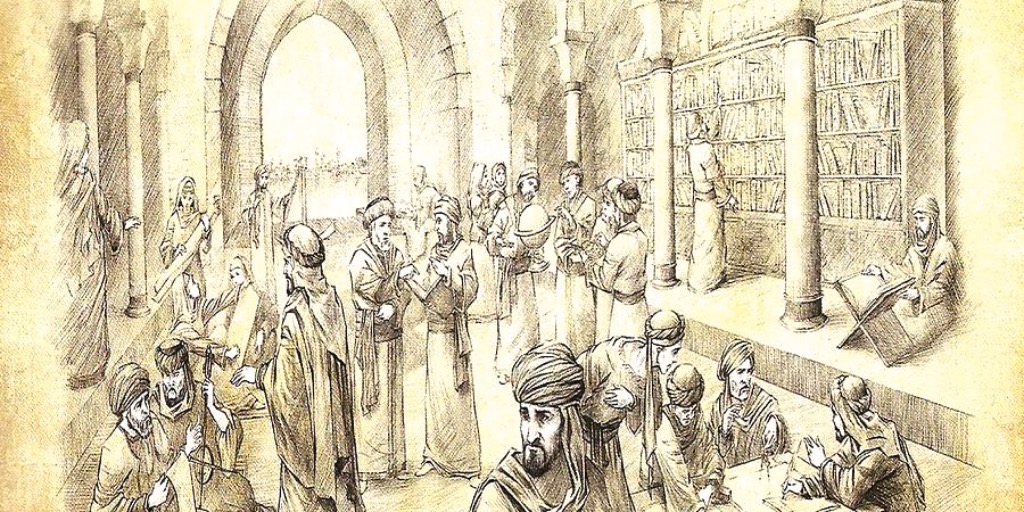

Baghdad’s House of wisdom, founded in the eighth century, was a flourishing hub of knowledge and science, the discoveries and inventions of which went on to influence the world.

Whereas today, we have imported Western ideals — in the way we speak, dress, and think — into our customs, there was a time when the Arab civilisation was an an exporter of innovation, invention, and advancements.

It was an era when knowledge was at the centre of the civilisation. The House of Wisdom was established during the Islamic empire’s golden age while Western Europe was still entrenched in what is known today as the dark ages.

During that time and for centuries afterwards, Arabic would become the international language of science. By the 12th century, discoveries made during Islam’s golden era would then be translated to Latin.

Scholars hailing from the region contributed to the advancements in several fields including astronomy, mathematics, natural history, and medicine, among others.

The term Algebra, a branch of mathematics, stems from the Arabic word al-jabr which was coined in the ninth century by Muslim mathematician, Muhammad Ibn Musa Al Khwarizmi.

Algebra, a branch of mathematics, was improved upon by Al Khwarizmi in the ninth century. While he did not invent algebra itself, he did revolutionise it.

The Arrival of Printing (and Mass Literacy) in the West

The invention of paper was a pivotal moment in history. It was first manufactured in China and began its journey to the West through the Arab region. With the widespread use of paper, printing would soon follow. The advent of the printing press brought about major changes to the global landscape as it allowed for the propagation of knowledge on a large scale in Europe.

At a time when mass literacy was at the budding stages of its development in Europe — as a result of the Gutenberg printing press — the Middle East and North Africa had already been witnessing a proliferation of knowledge 600 to 700 years prior under the Abbasid caliphate.

Taking a look back through the history of the Arab region and the advancements that these Arab thinkers and scholars brought to the world, one cannot help but feel a sense of pride at the achievements that were once synonymous with the region — and that were precursors to much of the progress achieved by the west today.

Being aware of the history that comes with Arab culture is pivotal in understanding our heritage and being inspired by our roots to reach new heights. Unfortunately, that has not always been the case in recent years.

View this post on Instagram

Since that period of flourishment within the region, Arabic has diminished in popularity among younger generations. It has drowned in a sea of negative stereotypes that equate it with lower socio-economic classes and a lack of education.

Once hailed for its beautiful intonations when it comes to poetry, Arabic seems to have fallen through the cracks. On social media, this epidemic is most apparent as one can find an endless slew of satirical videos portraying Arabs as they struggle to pronounce a certain word in English, or as they fumble the words.

While these videos may not have been made with ill intent, they speak to a deeper truth, an underlying problem: one of classicism where English or Italian or any other European language ia automatically linked to better education and a higher socio-economic standing.

This view of the Arabic language as somehow inferior or a source of shame is not limited to Egypt. In the Arab Youth Survey published in 2015, it was found that 36 percent of the younger Arab natives in Dubai speak English rather than their mother tongue in their day-to-day life.

In the Second International Conference on Arabic Language, which took place in 2013, participant Dr. Muna Al Saheli commented that, “we do not have pride in our language, which is the vocal expression of our identity because our colonist was successful in making us think it is inferior.”

She adds that, “they told us it is the reason behind our stagnation and was not fit for learning and [for] the sciences.”

However, as Arab natives of the upcoming generations put their mother tongue on the backburner in pursuit of a foreign language, an increasing number of non-Arab natives have, over the years, taken an interest in learning Arabic. While some foreigners learn it out of an interest in the region and culture, others may learn for religious purposes.

Arab Influence from Descartes to Digital Pop Art

René Descartes, David Hume, and St.Thomas Aquinas are a few of the names that come to mind when pondering the greats of philosophy throughout history. Much of their philosophical concepts, however, are heavily influenced by Arab-Islamic scholars.

Historians have found stark similarities between the works of Western and Arab philosophers. Descartes is said to have been heavily influenced by Iranian philosopher Abu Hamid Muhammad Ibn Muhammad Al Ghazali with comparisons being drawn between both scholars by Western and Arab intellects.

In his discussion “Influence of Muslim Thought on the West,” Pakistani college professor, philosopher, and Islamic scholar, Mian Mohammad Sharif (M.M.Sharif) iterates that “when the entire plan of their respective works, the whole treatment of the subjects discussed, and the whole content of these subjects down to detailed arguments, examples and relatively unimportant matter(…) run parallel to each other, it becomes impossible to attribute all that to coincidence,” when discussing Al-Ghazali’s influence on Descartes’ Discours de la Méthode (Discourse on the Method) — hailed as one of the French philosopher’s most influential books.

So, why has Arabic become a language linked to a lack of education when history has proven otherwise?

Observe conversations among your social groups, while most of them might lean on Arabic, a few words of English will inevitably slip in. This is particularly the case for those of us raised abroad.

One of the reasons for the Arabic language’s downward trend, from a social perspective, is that it is not deemed “cool.” This is as opposed to English, among other languages.

View this post on Instagram

However, there are individuals reclaiming their roots and giving Arabic a comeback. Many of the region’s young pop artists have been reclaiming their heritage by creating Arabic pop art. These are works of art inspired by Western styles while using Arabic calligraphy and iconic Middle Eastern figures.

Many of these young artists are looking to popularise the language again. In doing so, they are making a statement. They are taking pride and paying homage to their Arab roots — and rightly so. The works of these rising digital artists can be found on a medley of Instagram accounts celebrating our heritage, such as Arabic Pop Art and Eleutheria Arabi.

The breakthrough, exports, and discoveries made in the Arab world centuries ago continue to reverberate today. From philosophy to maths, these are just a few examples of the inventions these Arab-Muslim scholars brought to the world, there are, however, many more that have helped shape the modern world as we know it.

The opinions and ideas expressed in this article are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the views of Egyptian Streets’ editorial team. To submit an opinion article, please email [email protected].

Subscribe to the Egyptian Streets’ weekly newsletter! Catch up on the latest news, arts & culture headlines, exclusive features and more stories that matter, delivered straight to your inbox by clicking here.

Comments (0)