Last year, Raghda Hassan, coming from Upper Egypt’s Beni Suef, was getting ready to travel to Cairo to attend the ‘Miss Arab World’ competition, in which she designed the winner’s pharaonic-inspired gown that celebrates Egypt’s heritage.

“This was a very special dress for me. The order was made in one week and I had to do it all handmade,” she tells Egyptian Streets, “it was all hectic but it was worth it. I’ve been dreaming for this for a long time.”

This dream – which is often not given much regard- was growing steadily on its own from her hometown in Beni Suef. Coming from a family that works in handcrafts, Hassan started to develop a passion for the art of fashion at a young age, designing gowns for her friends and family members during special occasions. Gradually, from teaching herself through Youtube videos and getting inspired by designers like Elie Saab and Hany El Behairy, Hassan eventually opened her own atelier store ‘3roos‘ in 2010, and now designs for the yearly Miss Arab World competition.

Yet she is also aware that fashion is not just gowns, as it is commonly perceived in Egypt. “Many women here link fashion with just gowns to be worn during weddings or special events, and that’s completely wrong. They don’t care much for their overall everyday attire, and the idea of style is very much alien to them,” she says.

In other words, a woman is not just a mannequin in a gown, but is someone who moves and works in the modern world. As a free and equal individual in society, a form of dress must also reflect her physical and inner realities.

When Women Own Their Style

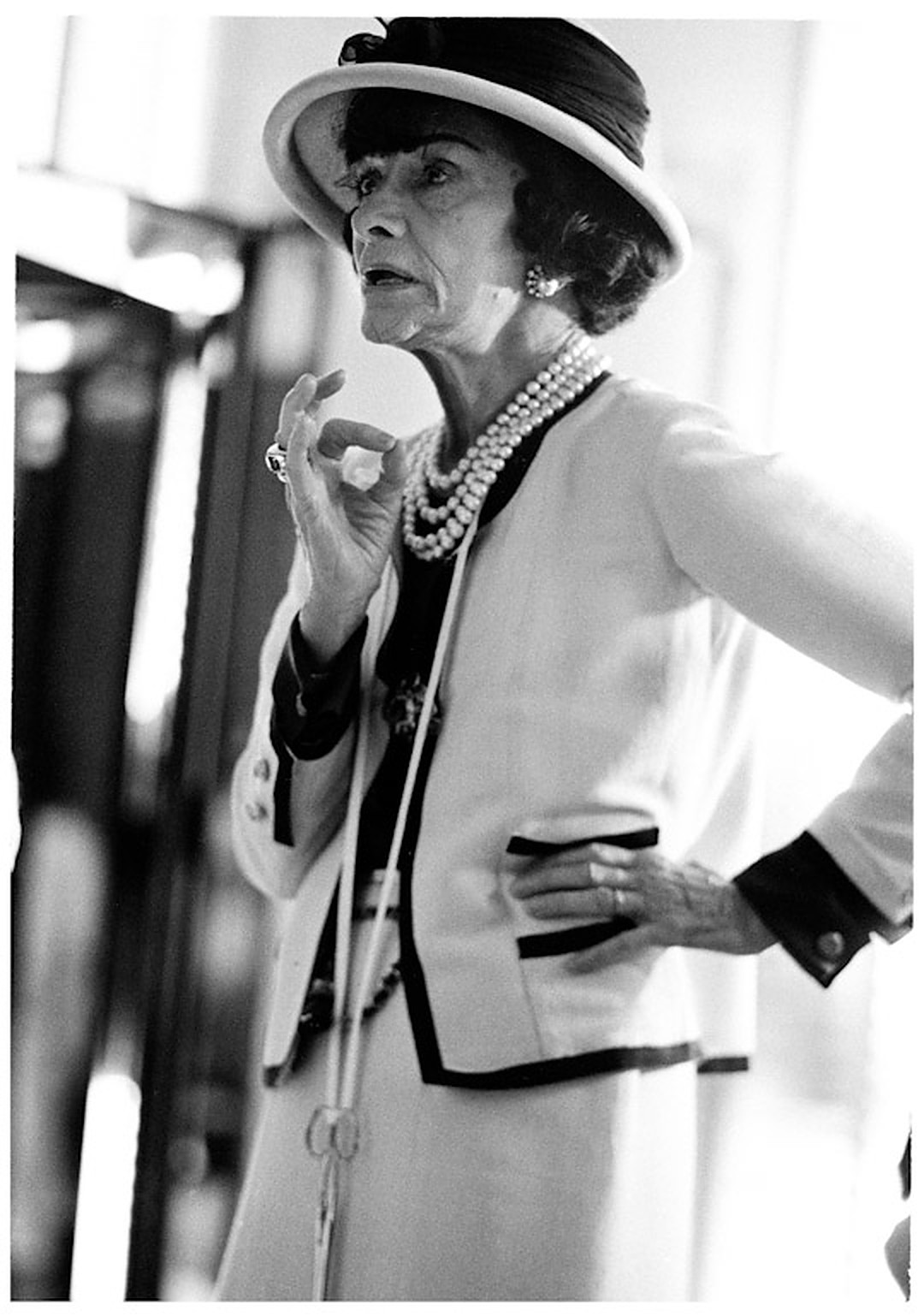

The idea of women owning their style – and self – has been a common challenge across the world. French fashion designer Gabrielle Bonheur – Coco Chanel – faced difficulties early on in the early 20th century in entering a male-dominated industry where it was often men who designed for women, leaving only the man’s perception of a woman’s identity.

The woman’s sense of identity, however, changed as female designers like Chanel began to take more ‘ownership’ of their style. She believed that a woman’s clothing needed to be created by the women who wore it themselves, and thereby, liberated women from the constraints and stereotypes that society held against them.

To reflect their realities after the events of World War 2, women’s fashion changed from corsets and hourglass shapes in dresses to a variety of dress shapes and sizes, including functional chic suits in comfortable fabrics to be worn as everyday attire for working women.

The idea of what is ‘feminine’ came to be defined differently as fashion changed. Representations of femininity through fashion changed throughout the twentieth century. In ‘Fashioning the Feminine: Representation and Women’s Fashion from the Fin de Siecle to the Present’ Cheryl Buckley, Hilary Fawcett and Hilary Moreton examine how ideas of femininity and women’s sense of style also evolved with Britain’s different social contexts. Women started seeing fashion as a spiritual experience to reflect their realities rather than it being something merely commercial or material.

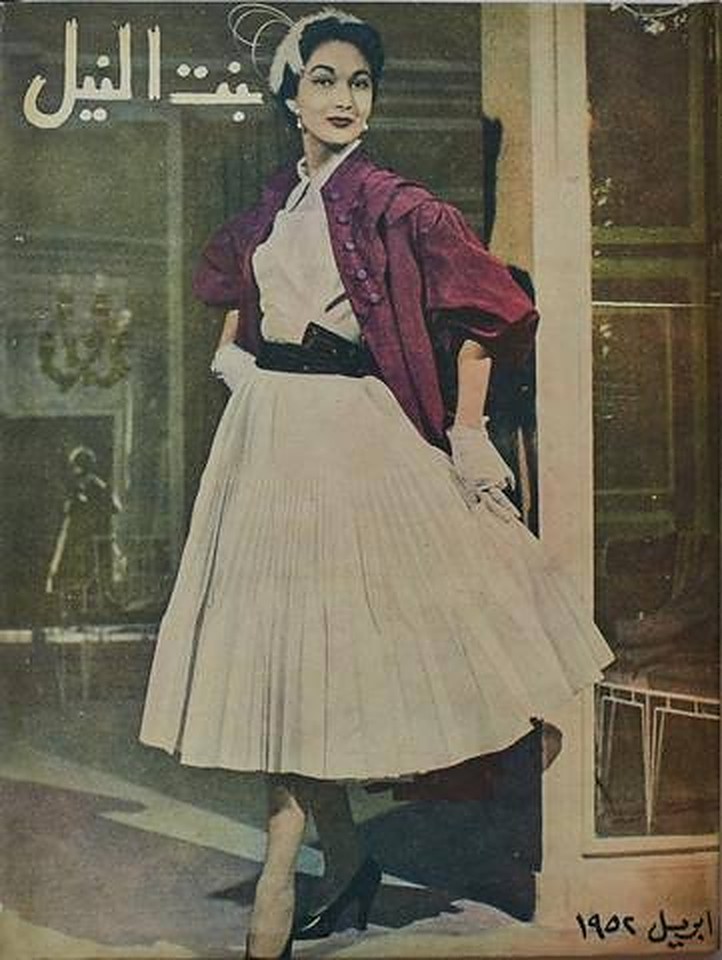

Egyptian women similarly went through phases of owning and disowning their sense of style, though at different levels due to colonial and historical contexts. Huda Shaarawi’s symbolic act of removing her face veil in public in 1922 was an expression of the changing realities of her time, moving towards national independence and the increasing sense of agency in Egyptian society. Later, as fashion for women in Europe was changing, it transferred to Egypt and became visible on screens and magazine covers such as ‘Bint El Nil’ (Daughter of the Nile).

Today, a number of Egyptian women like Raghda are capturing this power of ownership, though with much diversity – reflecting the complex realities of the current period that is yet gripped by different sources of identity. Whether veiled or unveiled, living in Cairo or Beni Suef, Egyptian women are gradually discovering their inner self through fashion.

RAGHDA’S ‘3ROOS’

Raghda Hassan’s ‘3roos’ atelier, which also grew to become a community group on Facebook with over 27,000 members, is an example of women in Upper Egypt becoming their own designers and creators of their feminine identity. Though she focuses on designing gowns, she also records videos on her page and Youtube providing lessons on everyday attire, and plans to organize more workshops and seminars to reach more women and revive the culture of fashion in society.

“Women’s knowledge of fashion here is very low compared to Cairo, but it is also still quite low in general in Egypt. I am trying to enhance their sense of style and teach them which pieces should be worn for what event and what occasion, and even with their Hijabs. I want them to truly express their femininity,” she notes.

Though Egypt’s streets are often packed with fashion stores and ateliers, Hassan notes that the number of designers still continue to fall, and it often turns more towards the commercial route rather than embracing the art of fashion.

“It is really rare when you find someone who designs something creative and unique that reflects the personality of each woman. It is usually something copied off the internet or from any other place, and it ends up looking misplaced or simply repetitive,” she says. “When they see dresses at El Gouna Film Festival or Cairo International Film Festival, for example, they would simply copy it, or the people themselves would ask for the same exact dress, with little regard to their own identity.”

When designing a gown, Hassan opts more for the traditional method of sitting with the client and trying to figure out their personality, sense of style, body shape and skin complexion. Despite her great success, however, she still faces challenges in trying to convince other women on the need to cherish the art of fashion. “The biggest challenge is trying to make people understand that this is not something trivial. Fashion is an entire culture of a society, it should be respected and taught,” she adds.

Echoing the words of the renowned fashion writer Diana Vreeland, “fashion is part of the daily air and it changes all the time, with all the events. You can even see the approaching revolution in clothes. You can see and feel everything in clothes.”

After completing a decade since opening her atelier in Beni Suef, Hassan hopes to expand to Cairo and even reach global audience. “I want to be able to share my designs with people all around the world, and to celebrate Egypt’s heritage through it,” she says.

Currently, women like Azza Fahmy, prominent jewelry designer, was able to achieve this after she entered the male-dominated jewelry market in Egypt many years ago and gave Egyptian women their own identity, translating Egypt’s heritage into art for global audiences. It is time for young and local designers like Raghda Hassan to also enjoy this same success.

Comments (5)

[…] even culture, with many different talents and designers, such as fashion designer Raghda Hassan who previously spoke to Egyptian Streets on her struggles and hopes in the fashion market in Upper […]

[…] even culture, with many different talents and designers, such as fashion designer Raghda Hassan who previously spoke to Egyptian Streets on her struggles and hopes in the fashion market in Upper […]