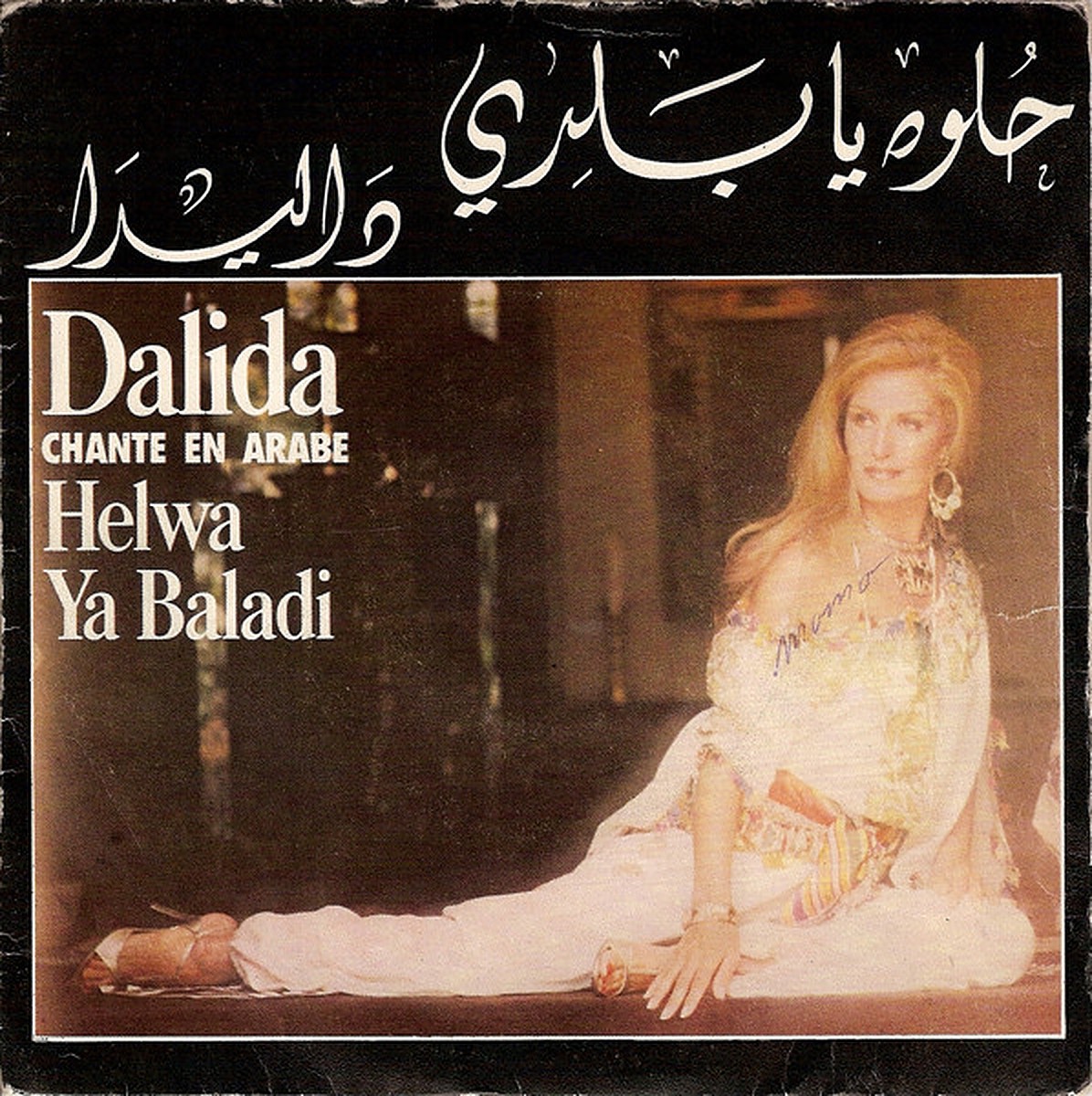

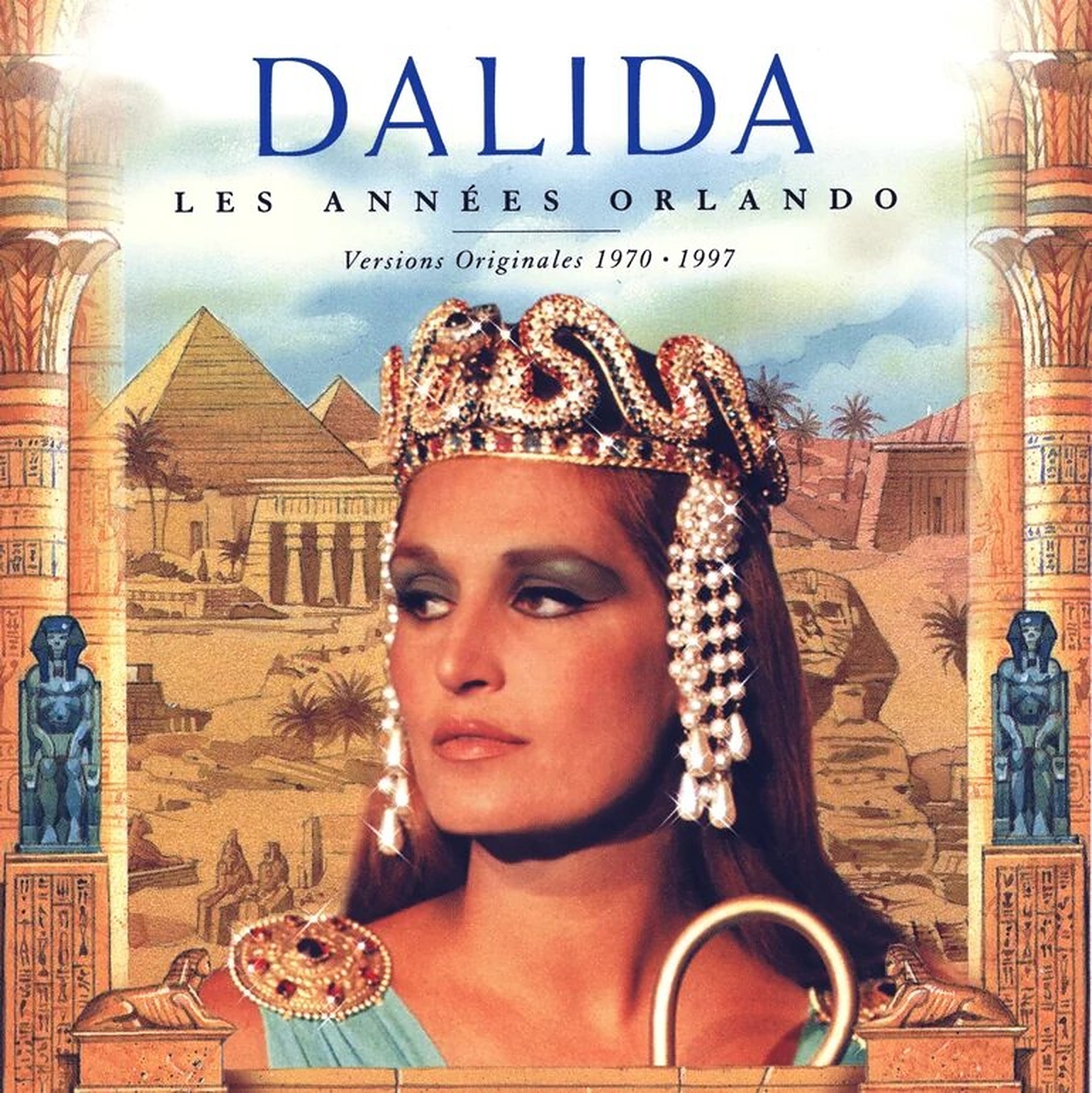

When you type “Helwa Ya Baladi” on YouTube, one of the first and most popular uploads that come up are usually those that feature the photo slideshows of Egypt set to the song by the legendary Dalida.

Written by Marawan Saada in the late 70s, the song became extraordinarily popular among Egyptians, and also later spread among others in the Arab world and Europe.

What made the song such a hit, however, isn’t its nationalistic element. There are currently countless of songs released possibly every year to ignite nationalistic pride among Egyptians, particularly since “Tislam al-Ayady” (God Bless Your Hands) that was released in 2013, and now recently “Ragel Ibn Ragel” by Nancy Agram that explicitly features Egyptian President Sisi in the music video.

If you spend just one day watching Egyptian TV, you are most definitely going to be hit with more than a couple of dramatic clips of a nationalistic song played alongside images and videos of Egypt. It has become too repetitive in the recent years that one cannot help but question whether the state is going through a political panic, or gripped by an unexplained hysteria that the state might soon face a doomsday scenario.

Despite the fact that music has for so long been part of the experience by Egyptians to express feelings of national belonging, there has been an unbalanced shift towards state patriotism that is now more associated with loyalty to the state – or the political leadership of a nation – rather than nationhood. In other words, state patriotism came to replace individual feelings of national belonging.

While state patriotism was often existent even back in the 50s and 60s, most exemplified by Umm Kalthoum, who Anna Drude Schou Pallesen describes in her research Singing the Nation as “a symbol of nation-building” through her long repertoire of patriotic songs that were in support of former President Nasser, there was yet still something distinctive that allowed her to maintain such popularity. Coming from humble origins as the daughter of a rural village cleric, and existing during the aftershocks of colonialism, Umm Kalthoum was able to craft her image in a way that was relatable and organic, choosing music and lyrics that expressed the emotions of the Egyptian people.

Through her songs, Egypt was seen through the voice of Umm Kalthoum, rather than through its political leadership. She was able to create her very own symbol of nationhood, which stemmed from her individual and personal experiences of pride and belonging.

When I first heard ‘Helwa Ya Baladi’, it was from a random Egyptian TV commercial I saw as a child in the early 2000s. I was the daughter of a generation that migrated to the Gulf by the start of the 21st century, and the only connection I had with Egypt was through this particular song, which my mother used to occasionally hum and play as she made us breakfast during early Friday mornings.

I still vividly remember the moment I heard the song play on TV, and how the images of Egypt were shown as the song starts with the memorable first verse: “I always hoped to return to you, my country, and stay beside you always and forever.”

As a child, who only faintly understood the lyrics of Umm Kalthoum and Abd El Halim, Dalida’s emotional cry to return to her homeland became the only real connection I had with Egypt, and developed my own perception and understanding of nationhood and belonging.

I started to see Egypt through her music, which centered on feelings of nostalgia from old Egyptian songs, as she sings in ‘Aghani Aghani’, and when she says in Helwa Ya Baladi “we’ll both sing this most beautiful tune,

the words “my country” are so beautiful in a song between two lines.” Her own personal experience of leaving the country, which came to create her feeling of belonging with Egypt, was something I was able to relate to.

Egypt, for me, was known through its music. It was a song that my family would dance to during weddings or celebrations, or the voice of a national icon such as Umm Kalthoum. It was the soul of a people connected through similar human experiences, as Dalida expresses in the song.

It is the creation of that soul – that distinctive emotional element – that is missing in most of Egypt’s current nationalistic songs.

Comment (1)

[…] Seeing Egypt Through Dalida’s ‘Helwa Ya Baladi’ Number of Minya Microbus Crash Victims Soars to 5, 16 Injured […]