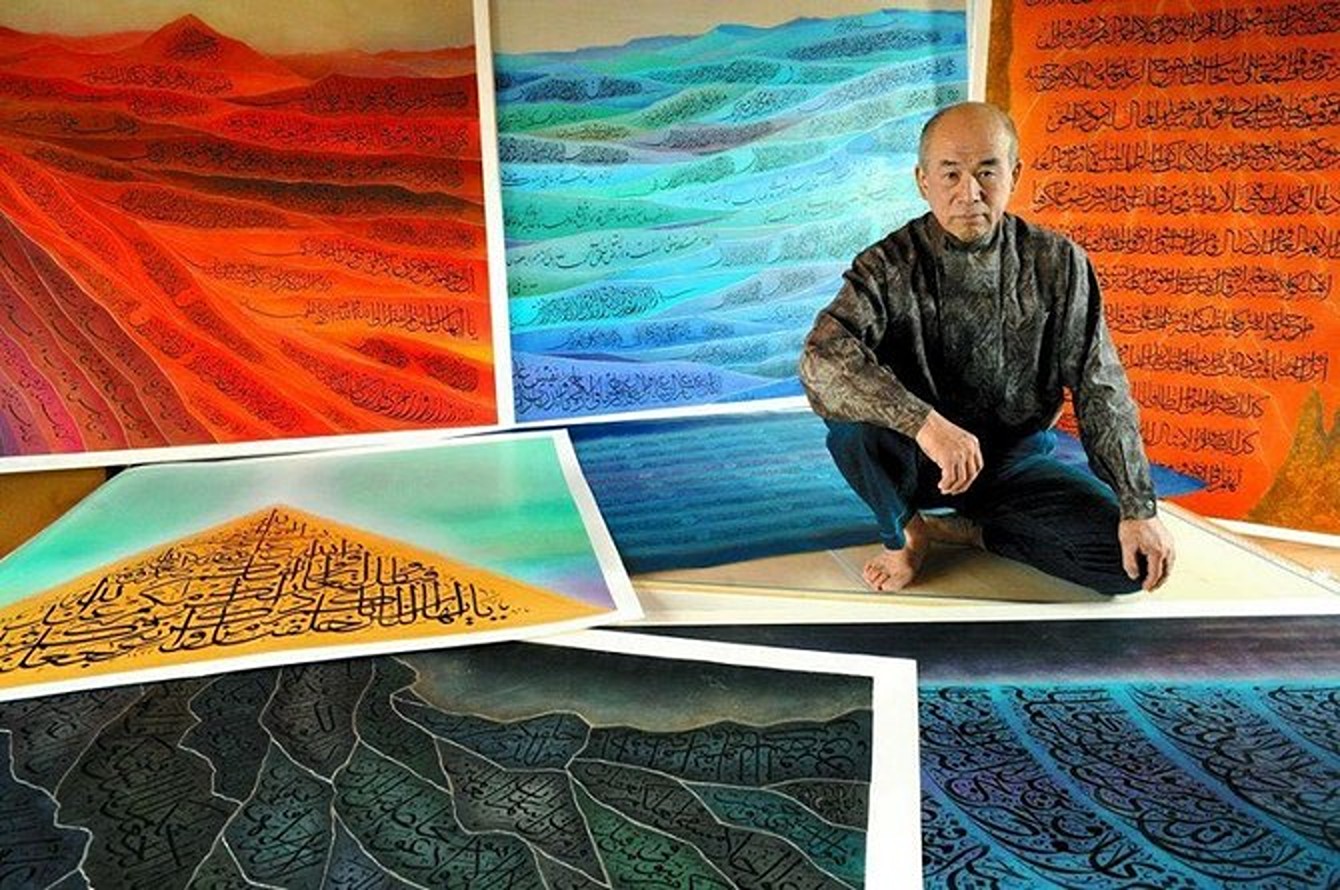

Fuad Kouichi Honda, a renowned Japanese artist and Arabic calligrapher, once described the Qur’an as “music without sound.”

For him, the Qur’an’s verses are more than just static words on a page; they are moving expressions of life itself. For instance, the essence of life could be captured in a single word: water.

This sentiment is reflected in his art, which bridges the gap between Islamic art and Japanese aesthetics. Each color, each curve, and each variation in thickness is meticulously chosen to evoke the spirit of the Qu’ran’s verses.

“Words about water have a very profound meaning,” he once said. “Water is important in the Qur’an as it has different shapes every moment and this is shown in my design.”

His work transcends mere cultural exchange; it elevates Japanese art forms into expressions of Islamic spirituality, and in turn, imbues Islam with a new layer of meaning, enriching his own personal faith.

But Honda is not alone in his artistic fusion. Beyond Fuad Kouichi Honda’s work, a long history of influences connects Japanese and Islamic art forms, despite the current lack of widespread awareness. Both cultures prioritize beauty, symbolism, and a focus on the divine in their artistic traditions.

Trade Routes and Ancient Artistic Exchange

The Silk Road, a network of interconnected trade routes that flourished from the 8th century onwards, provides the most significant link between Islamic and Japanese art.

This network facilitated a vibrant exchange of goods, knowledge, and artistic styles. Islamic textiles, ceramics, and metalwork, renowned for their intricate geometric patterns, vibrant colors, and calligraphy, reached Japan and influenced its artisans.

The Ottoman Empire’s expansion into East Asia, particularly the Malay peninsula, further fueled this artistic exchange. This influence flourished in various artistic mediums, including textiles, woodcarving, and manuscript production.

The keris, a distinctive asymmetrical dagger, became a prized luxury item, often incorporated into formal attire. Additionally, the art of silver filigree, a form of metalwork used in jewellery, reached new heights, producing intricate designs on a variety of objects, from jewelry to everyday utensils.

The artistic exchange extended beyond geometric patterns. Lush green landscapes of the Malay region inspired motifs featuring floral designs, birds, and domesticated animals, adorning wood, metal, and especially Islamic textiles.

Textiles held a particular fascination for Japanese connoisseurs. This appreciation continues today, with the example of kimonos — a traditional Japanese garment — being crafted from songket, a luxurious fabric woven with metallic threads. Another shared artistic passion is batik, a dyeing technique that remains popular in both the Malay world and Japan.

Modern Art Influences

The influence of Islamic art extends beyond aesthetics in modern Japan. It also resonates with artists who seek to imbue their work with spiritual depth and explore themes of morality.

A great example is found in the work of Qayyim Naoki Yamamoto, an assistant professor specializing in Ottoman Sufism and traditional Japanese culture at Marmara University’s Graduate School of Turkic Studies. Yamamoto’s work highlights the use of manga, a popular Japanese comic form, as a tool to educate and introduce Sufi religious concepts to the Japanese public.

The emphasis on moral themes within manga creates a bridge between Islamic art and Japanese artistic expression.

According to Yamamoto, one reason manga resonates so strongly with Japanese readers is its ability to visually convey emotions and spiritual messages alongside dialogue. This emphasis on visual storytelling reflects a cultural preference for nonverbal communication, allowing readers to deeply understand characters’ emotional states beyond just the words they say.

Historical accounts suggest a deeper connection between Islamic art and manga’s development. The Muslim world had a rich tradition of illustrated storytelling, particularly in the Persianate world encompassing Ottomans, Iran, and Mughal India.

This tradition, exemplified by miniatures that flourished under Mongol patronage in the 13th century, may have further influenced Japan’s existing emakimono scrolls. Notably, during the Pax Mongolica, illustrated storytelling thrived under both Muslim and Buddhist converts to the Mongol Empire, potentially creating a bridge between Islamic artistic styles and Japanese narrative traditions.

This shared history of visual storytelling, employed by both Sufis and Japanese artists for centuries to convey religious ideas and educate new populations, hints at a possible influence on the evolution of manga from the earlier emakimono format.

Yamamoto noticed many similarities between Sufism and manga, arguing that forms of expression in anime and manga can also be used to convey Sufi ideas. Sufi tales, centered on the protagonist’s journey towards spiritual perfection by conquering the ego, share a structural similarity with manga. Both emphasize the significance of a mentor figure. In Sufism, a trusting relationship between the disciple and the master is paramount. Similarly, manga heroes like Naruto in the popular series ‘Naruto’ are guided by various sensei (teachers) throughout their growth.

These influences prove that the artistic dialogue between Islam and Japan extends far beyond ancient historical influences. The breathtaking beauty of Honda’s Arabic calligraphy and the presence of Sufi spiritual messages integrated into contemporary Japanese manga illustrate this ongoing exchange.

Islamic and Japanese art forms act as a shared language, continuing to speak volumes about faith, beauty, and the human experience through the artistic expressions of both cultures.

Comments (0)