World-renowned Egyptian-American economist Mohamed El-Erian has described the current moment in history as a “generation-defining” one.

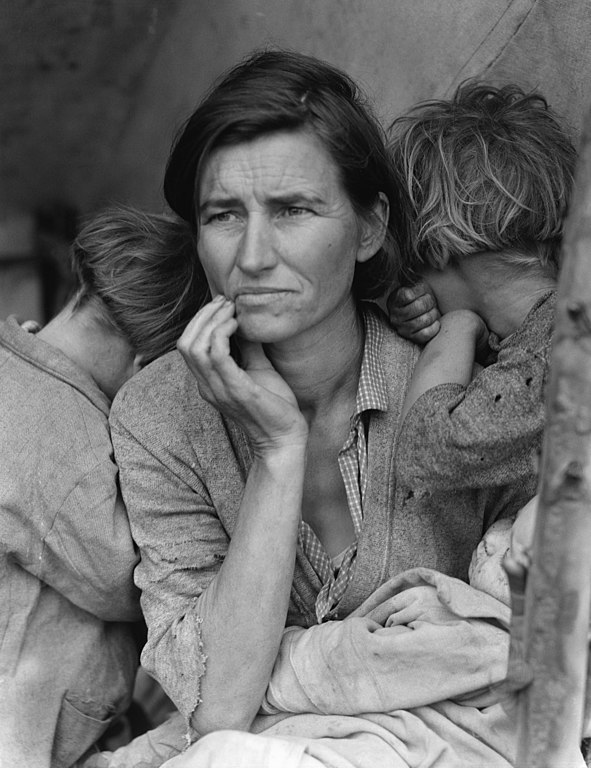

With the world in the midst of the worst public health crisis since the so-called Spanish Flu in the 1920s and the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression in the 1930s, the path today’s generation of decision-makers choose will, in El-Erian’s view, determine how future generations will come to define them.

Currently chief economic advisor at multinational financial services company Allianz and incoming President at Queen’s College, Cambridge in the UK, El-Erian’s has arguably become the most authoritative voice in analysing the crisis and suggesting the ways in which policymakers and business leaders should react. In part, this stading stems from his astute commentary on the 2008 financial crisis.

Neither optimistic nor pessimistic, he has been pointing out the challenges, opportunities, and new realities this historic crossroads presents.

A World Economy in Crisis

“This will be the worst recession for the advanced economies since the Great Depression of the 1930s. This will make the Global Financial Crisis [of 2008], and the Great Recession that followed, look mild,” El-Erian said in a recent talk.

While the 2008 economic crisis hit the financial system without registering any significant effect on supply and demand, the current crisis is an intentionally induced standstill of economic activity, with both supply and demand falling drastically due to a variety of lockdown measures and temporary closures.

Although advanced economies are those contracting most evidently, El-Erian states clearly that developing economies cannot “decouple [themselves] from this reality”.

As the world faces a global spread of a highly transmissible virus and a consequent economic crisis, governments, and corporations alike are facing a delicate and decisive choice between what El-Erian refers to as lives and livelihoods.

While protecting the lives of citizens requires isolation, economic activity, which provides their livelihoods through jobs and incomes, depends on interaction.

However, as economies will not be able to return to any semblance of normality while the public health crisis persists, El-Erian believes that resolving the public health crisis should take precedence over resolving the economic one.

The health problem must be tackled first in his view, in parallel with finding and implementing measures to alleviate social impact and help businesses avoid bankruptcy. This way, he believes, short-term problems of unemployment and struggling businesses will not grow to become long-term problems.

The Road Ahead

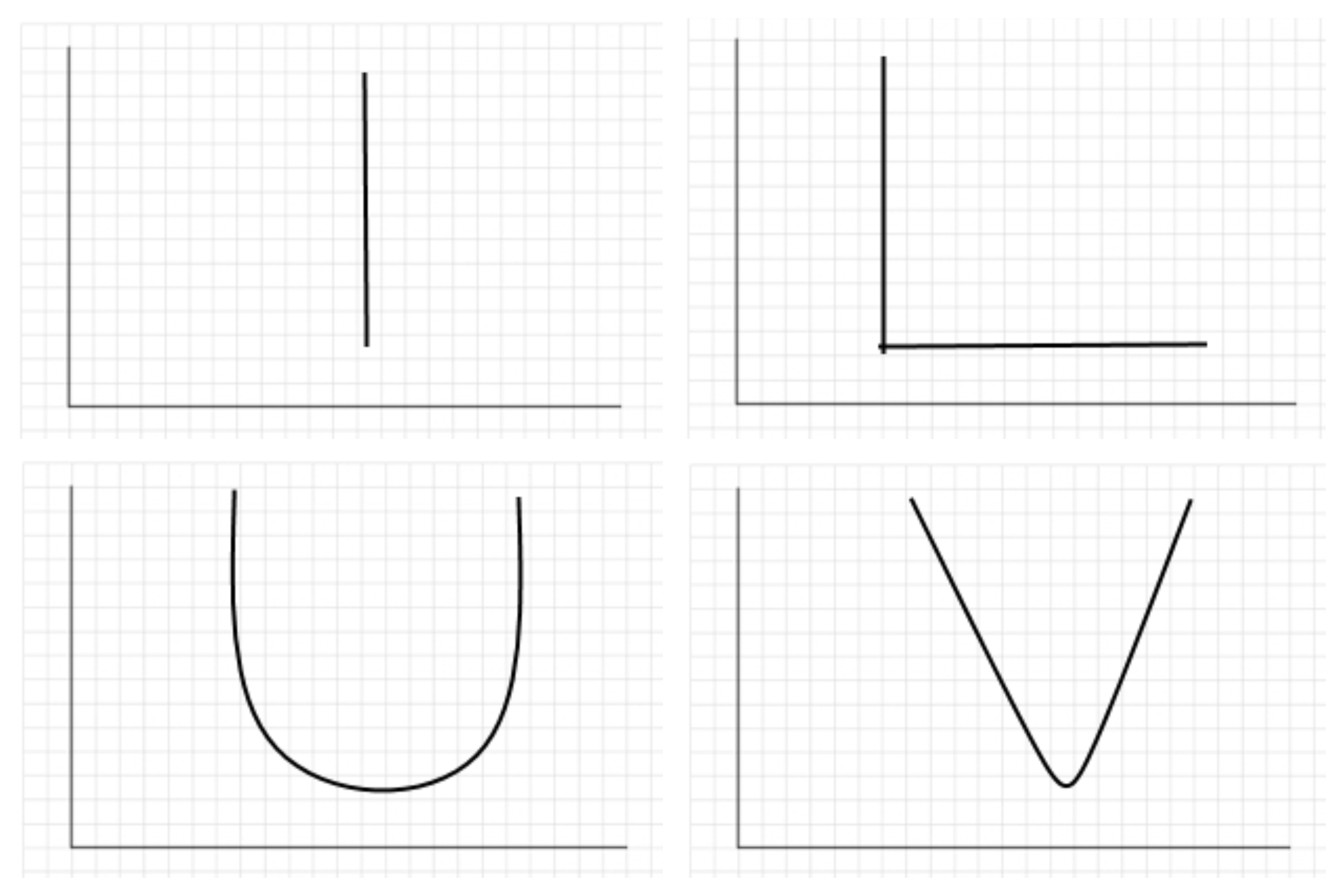

To illustrate the trajectories economic growth could take as it tries to recover from the coronavirus-induced standstill, El-Erian explains that the curves describing economies in crisis take a number of different shapes resembling letters of the alphabet: I, L, U, V.

An I-shaped curve falls straight down, indicating a sharp drop in growth. An L-shaped curve describes an economy whose growth falls sharply then stabilises at a lower level of activity without rising. A V-shaped curve is the most desirable scenario in the wake of a crisis, in which after falling sharply, economic growth shoots right back up, and finally, a U-shaped curve describes a scenario in which growth falls, stabilises for some time at a lower level, then begins to rise once more.

Seeing little possibility of a V-shaped recovery, El-Erian believes that a U-shaped curve can still be hoped for in the current crisis. However, given the nature of pandemics, the world economy could find itself experiencing an entirely different curve – one that is shaped like the letter W, where as soon as the economy begins its recovery, a second wave of infections would hit, once again and causing a drop in growth, which is ideally followed by a return to growth.

But these are descriptive models that do not necessarily contain any suggestion of the right course of action. El-Erian is more concerned with what follows a successful recovery than the recovery itself.

“When you are faced with a war, the challenge is not simply to win the war, but to secure the peace,” he says, likening crisis to war and reaching for concepts borrowed from foreign policy and defense.

He elaborates that in the case of the financial crisis and subsequent recession of 2008, the war was won by avoiding a depression and returning to growth, but the peace was not secured, leading us into the current crisis ill-prepared.

Breaking, like a growing number of economists nowadays, with the neo-liberal ideas that dominated economic thought in recent decades, El-Erian believes that post-2008 growth has not been sufficiently inclusive, did not prioritize sustainability, and placed little emphasis on fighting inequalities and protecting the planet. He believes that this failure put us in a worse position in facing the current crisis.

He also predicts that globalization may very well become one victim of the current crisis. Not to be conflated with the current standsill in travel and trade induced temporarily to limit the spread of the virus, decreased dependence on international trade and increased attempts of self-sufficiency due to the breakdown of supply chains during the crisis and the fear of over-reliance on foreign sourcing will lead to a process of de-globalization.

Moreover, he forecasts higher levels of debt across the economy, especially that governments will borrow heavily to meet the challenges of the crisis, including funding the private sector, which, along with massive central banks’ capital injection in capital markets, thus increasing government involvement in the economy.

He concludes that this could lead to lower productivity, and consequently less growth, and less equality in income, wealth and opportunity. Alluding to the term he coined after the 2008 crisis, El-Erian fears that this means that we will face a compounded version of the “new normal”.

He has so far been reluctant to prescribe any detailed course of action beyond crisis mitigation, emphasizing the importance of being sufficiently flexible and agile to deal with a variety of scenarios.To highlight the importance of agility, he warned of what he referred to as active inertia, which is the tendency to apply familiar policy responses to new circumstances, even if they are not necessarily suited to solve the problems at hand.

Humorously using his love for the Egyptian football team Al-Tersana to construct an analogy, he pointed out, in a recent talk, that the management of the current crisis requires policy makers to have a solid defence, which he argues is embodied in resilience and optionality, and a strong offence, which is embodied in agility.

El-Erian laments the lack of coordinated global response to the current crisis, especially in contrast with the one of 2008, although the crisis is clearly a global one.

Egypt in Focus

In a webinar held by Nile University in April 2020 and attended by influential figures such as Amr Moussa, Heba Handousa, and Hossam Badrawy, El-Erian discussed economic management in the time of this global pandemic. Throughout the webinar, El-Erian was cautious in expressing specific thoughts or ideas about the impact of the pandemic and Egypt’s response, however he gave away some thoughts, particularly prompted by the Q&A portion.

He touched on some of the ways in which developing countries – among them Egypt – have been affected by the public health and economic crises, “lower export volume, lower commodity prices, […] lower remittances, lower tourism, […and] lower foreign direct investment.” He praised Egypt, among other countries, for taking initiatives to support affected sectors of economy early on.

Addressing the impact on foreign investment, he differentiated between two motivations for such investment: uneducated investment, which he also refers to as tourist capital, which flows out of its home due to lack of opportunity, and educated investment, which he also refers to as resident capital, which comes to the market seeking specific opportunities it identified beforehand. The former tends to be significantly less committed than the latter.

Egypt is among the countries that have in recent years been attracting more tourist capital, as low interest rates in industrial countries have pushed foreign investors to seek higher yields. The motivation for investment here does not lie in any factors inherent in Egypt’s profile and thus is more likely to withdraw in times of risk and crisis. Therefore, he is expecting little of such investments in the coming months.

Resident capital on the other hand, stems from more knowledge about Egypt and its economy, and is therefore more likely to stay throughout times of crisis and risk, as its presence in Egypt hinges on more than simply economic convenience.

“Don’t think that because the tourist money isn’t coming that the dedicated money isn’t going to come,” El-Erian said in the webinar.

He also showed some optimism about Egypt’s chances of growth and self-reliance in a world that may be facing a move toward de-globalization. Coming into the crisis, Egypt had high international reserves, falling inflation, an educated labor force in the formal sector and a flexible informal sector which may strengthen its ability to power through this crisis.

While emphasising the importance of the government’s role in the relief effort and the facilitation of the recovery, El-Erian concluded the webinar on a hopeful note:

“[Here in Egypt], if we just put our mind to it, we can be resilient in a way that helps us manage both the journey and the destination.”

Comment (1)

[…] https://egyptianstreets.com/2020/06/08/a-generation-defining-moment-el-erian-stresses-the-weight-of-… […]