My parents spent their first six years post-migration to Australia immersing themselves in their new culture. A series of transient forces saw them trade their life in a small country town by the Nile delta for a new beginning in Whyalla. It wasn’t until I was born that they realised their responsibility to recreate a sense of Egypt for their children.

This meant a childhood tinged with the sounds, scents, and colours of my parents’ motherland. The sound of Umm Kulthum’s strong voice on cassette. The scent of toum and vinegar teasing the fatta we would be having for dinner. The colours of khayyamiya decorations attempting to replicate an Egyptian Ramadan within the walls of our living room.

The fruits of such efforts blossomed into moments where my mouth formed the difficult sounds of my second language, where the jokes of Adel Imam masreheya’s were not lost in translation, and my hips moved along to the beat of Nancy Ajram songs.

As I’ve entered adulthood, I’ve become more aware of the nuances inherited from my parents. No longer did I look at their faces searching only for the genetic links between our curls or hooked noses, I started to look for the nexus between our values, thoughts, and feelings.

My dad taught me that “hard” and “work” are two words that exist in tandem, my mother that hospitality and generosity are a way of life, and together they passed on to me and my siblings a strong nostalgia for Egypt.

Nostalgia, derived from the Greek words nostos ‘returning home’ and álgos, ‘pain’, is an inherently sentimental state and not necessarily tied to reality. Symptoms of this pain manifest themselves in migrants in various ways. Some search the new home for kindred souls for whom home is also out of reach. Others may spend their lives feverishly returning to the motherland looking for their ‘fix’. For some, the preferred coping mechanism is to cut ties with the motherland entirely.

There are two types of migrants. The temporary migrant is the one who intends to return to the motherland once the purpose of migration – whether that be education, work, or simply experience – has been served. This migrant can afford to be geographically elsewhere whilst remaining mentally fixated on the motherland.

But for the other – the migrant that intends to set roots down in their ‘new’ homeland – it is their mind, body, and soul that migrates with them. My parents, who packed up their family home in ¬al-Gharbeyyah into a couple of suitcases and for the last 30 years have attempted to build a new family home in Australia, fall into the latter.

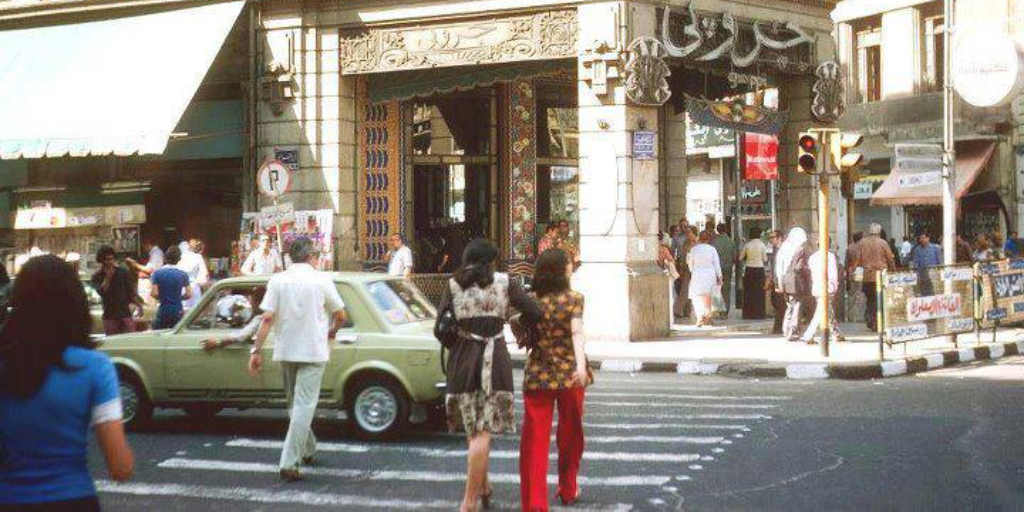

My parents medicated the pain of their loss of home with constant family trips back to Egypt. Yet, the more trips I took back home the more I realised the Egypt that my parents sold to me didn’t add up to the reality I was introduced to. The cultural toolkit I inherited from my parents did little to help me connect with my cousins overseas. We hadn’t seen the same movies, read the same books, and any ability to discuss our polar opposite worldviews was inhibited by a language barrier.

In the Venn diagram of our shared experiences, values, and interests any overlap was merely due to familial bonds. I had grown up so surrounded by what I thought was Egyptian culture, yet the very Egyptians I thought I was emulating didn’t recognise my cultural currency. By the end of each trip I would leave feeling confused – did the Egypt of my parents ever really exist?

Migration is a perpetual existence – the migrant becomes neither of here nor of there. My father confesses over late night cups of shay that Egypt no longer feels like home, and yet the new home has never been able to fill that void either. Instead, the migrant ends up carrying their sense of home within themselves.

Home becomes less attached to something tangible – it isn’t a place, or a building, or a person – it is a feeling. This emotional baggage becomes intrinsically tied to the migrant’s perception of the motherland. It is no wonder that they view the time and place where such complex emotions have not yet come to fruition as a safe haven of sorts. My parents view Egypt with the rose-tinted glasses that they donned the moment they left the stability of their homes.

It would be remiss of me to ignore that my parents left an Egypt that was on the precipice of great social movements. Egypt was not immune to the kinetic energy of the turn of the century. In 1990, the Former President Mubarak was nearing his tenth year in power, tourism and the economy were booming, and the return of Egyptian expats from gulf nations saw the Islamification of the middle classes. There is no doubt that these factors played a role in creating the fissure between my parents’ perception of Egypt and the reality I was welcomed by in trips back to Egypt.

The over-arching lesson of my parents’ life is the idea that nothing is fixed, and everything is changing. My father was well into his 30’s when he migrated and left his career as an engineer to start a tailoring business in Australia to support his growing family. My mother left behind loved ones and with her broken English, forged equally meaningful connections with Romanian neighbours. Even the very country they left has not escaped this evolution as it has undergone a complete overhaul – more than once in the last few years alone.

For us second generation kids the experience of ‘growing up in diverse Australia’ isn’t over. We’ve inherited our parents’ feelings of being of neither here nor of there. In Egypt, I become hypersensitive to the fact that I stick out as a ‘westerner’ and walk the streets attempting to shrink myself.

Yet, here in Australia I’m met with curious attempts to guess my ethnic background. My teenage years were punctuated with phases that fluctuated between resisting and embracing the baggage that comes with a second culture. It has taken years of engaging in a cultural tug of war to form my current sense of self. As with any second-generation migrant, my identity has been formed both by, and in-spite of, this cultural clash.

To be a second-generation migrant is to use the building blocks of your parents’ experience and grow beyond with the opportunities of your birthplace to self-determine a culture, traditions, and ideals. The purpose of my parents’ migration was to provide me with a life free of the shackles of their own. A responsibility that they continued to assume when they enrolled me in my primary school as ‘Emma’ not ‘Eman’ attempting to help me assimilate.

As I’ve grown older, introducing myself as Eman – spelling it out and correcting pronunciation – is just one of the small aspects of my identity I’ve reclaimed agency over. It’s a small step in creating a culture that is not necessarily new, rather it is an amalgamation of the melting point of cultures we live in and the ever-changing motherlands.

There is no anecdote that can accurately portray the intricacies I have faced navigating our multi-ethnic, multi-religious, multi-cultural society. My experience growing up in Australia does not exist in a vacuum. I stand on the shoulders of the giants that are my mama and baba. Perhaps through growing to understand them, and their experiences, you will grow to understand me too.

*The opinions and ideas expressed in this article do not reflect the views of Egyptian Streets’ editorial team or any other institution with which they are affiliated. To submit an opinion article, please check out our submission guidelines here.

Comment (1)

[…] You can check out the article here: https://egyptianstreets.com/2021/02/18/diasporic-nostalgia-for-an-egypt-which-no-longer-exists/ […]