Imagine a Coptic Egyptian Community Center in the middle of a southern state in the United States with services such as a clinic and a lawyer on the top floor, Arabic-speaking restaurant and business owners on the bottom floor, and a plaza that is decorated to celebrate Egyptian culture. This is the vision Lydia Yousief has for ‘Elmahaba’ in Nashville, Tennessee.

According to the 2016 U.S. Census, there were 181,000 Egyptians in the U.S., however, the number is believed to be much higher. Unlike the upper and middle-class Coptic communities in New York, Washington DC, and the Los Angeles area, Tennessee has a majority working-class community. Egypt is estimated to be around 10 to 15 percent Christian and 85 to 90 percent Muslim, but in Nashville, over 90 percent of Egyptians are Coptic Christian.

Nashville, the capital of the U.S. state of Tennessee, is home to what some call “Little Minya”, a minority community composed of thousands of Egyptian Copts, largely from the Upper Egyptian city of Minya with approximately 50 percent of its population being Coptic Christians.

In this community, most people work in the hotel industry and in factories, with few starting small businesses because of the lack of universal health care in the U.S.. In 1998 there were about 300 Egyptian families in Nashville and they were mostly all working at Opryland Resort.

In the 1950s, Nashville was a small Southern city known for country music, but from the 1970s on, Nashville started to be a refugee relocation site for Hmong refugees from the Vietnam war and Kurdish refugees from the first Gulf war. With the migration of Africans from Egypt, Ethiopia, and Somalia, the population quickly increased. The then-regional airport became international in 1987, and the factories grew larger.

With Nashville as a new hotspot for music, people from California and all over the U.S. started coming to the city. This resulted in issues of economic inequality for the city which was growing quickly atop a layer of Latinx and African immigrants who built the tourism industry that Nashville thrived on.

Immigrant Segregation

With Coptic Christians attending services at church, their Muslim neighbors going to the mosque, and the Ethiopian Orthodox Christians going to the Ethiopian church, the isolation started growing between the community, particularly after COVID-19.

“We are neighbors, we all work together, we go to school together. We are one community, what hurts you hurts me, what strengthens you strengthens me. Instead of having that mentality, there’s an extreme push for segregation,” says Lydia Yousief, Egyptian-American founder of Elmahaba Center.

“And that’s not something organic, you have to manufacture that, to tell two people who are living next to each other who are working together in the same factory that their issues are not the same.”

During the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, one of the institutions that was offering culturally appropriate food in the largely-immigrant South Nashville area was the local mosque, Yousief says.

“We were telling people to go to the mosque in Antioch which was very accessible. A lot of Coptic people would say ’I’d never go to a food bank where Muslims are doing it.’ That type of animosity comes from a problem within our own community not to appreciate and support each other which showed during the pandemic,” Yousief says.

Another symptom of segregation in Nashville is in housing. Many immigrants first arrived in Millwood, which Yousief describes as a ‘ghetto’ where African immigrants have lived for decades and have been paying high rent for apartment buildings that are cockroach-infested with leaks, broken water pipes, and overall poor living conditions.

Additionally, Millwood faced a destructive flood in 2010 that greatly affected the Egyptians and others living in the area.

“When we tell ourselves, ‘I’m Coptic and therefore I’m better than someone who’s Ethiopian, I’m better than someone who’s Muslim.’ That translates into ‘I’m an upper-class Copt, I’m better than a lower-class Copt who works in a factory.’ So, one of the things we focus on is the Coptic community because it takes a lot of healing to say we have to love ourselves first before we begin to approach and build relationships,” Yousief adds.

Part of the rise of sectarianism is indoctrinated in the factories where most working-class people in Nashville work, Yousief says.

“Tyson Fresh Meats; they pit Muslims and Christians against each other, especially Somalis and Coptic people, and they make sure to work that sectarian rift between their workers. So they [the immigrant population] are working in a community where everything is working against them,” Yousief alleges.

She adds that the competition between workers is done to prevent unionization efforts in factories, which had happened before in other factories.

Tyson Fresh Meats had a racial discrimination lawsuit filed against it in 2014. However, it was later dismissed and no further comments were made regarding the treatment of African immigrants in the factory.

Second-Generation Economic Immobility

For Nashville Egyptians, second-generation immigrants are not more financially successful than their parents. They are working in factories, hotels and mechanic shops, with a significant minority not going to college because it is not affordable.

“Ironically, the first [Coptic] people here who came to Nashville came as science-related degree [students] at Vanderbilt University. So, you have 30 years of people who came to Nashville to pursue degrees, and now you don’t have that. We don’t have many Coptic people who are doctors, teachers, speakers, artists, or musicians. We have one journalist, no one in the humanities, and no historians at all,” Yousief says.

The push for Yousief to start Elmahaba was that the nonprofit sector in Nashville does not offer assistance to people who only speak Arabic, a population of approximately 20,000 people, Yousief says.

In the cultural centers at the time, which were the 10 Coptic churches in Nashville, services were limited and isolating from the outside world. In the southern diocese, Yousief says, the churches have been known to corner off people from receiving services from outside the church.

“They say ‘we are going to provide these services for you, if you’re having trouble applying to colleges, we’ll do that, you don’t need to speak to college counselors. If you’re having marital issues, don’t go to a marital council counselor, come to us’ and socially round off Coptic people, which causes a lot of tension because the church is incompetent in offering the services in Nashville and it socially isolates a lot of Coptic people,” she adds.

Nashville Coptic Egyptians had been experiencing lack of support from non-profits, allegedly hostile work environments, and single-source help from the churches. This is the atmosphere that motivated Yousief to start Elmahaba in 2019 after finishing her Master’s degree in Middle Eastern Studies.

Starting a Not-for-Profit

Not-for-profit was the way to go for Elmahaba from the start, with the goal of providing the services that are needed in a culturally appropriate and competent environment. “That would be very easy,” Yousief thought; to mobilize those who have been in Nashville for 20 years to help more recent immigrants from Egypt not make the same mistakes and not work in the same factories.

Elmahaba Center started in June 2019 with Yousief, her sister Erinie, and Veronica Nashed, who all had experience working with not-for-profits and grew up in the Coptic community.

“I contacted Veronica, and said, ‘I have a crazy idea. Why don’t we start a nonprofit for Coptic people in Nashville?’ Veronica has a background in workers’ rights and housing rights. We sat down from June to July 2019, mapping out what we wanted to do, and formulated the whole nonprofit, because we knew in five years, Nashville was going to be different and we wanted Elmahaba to be very flexible, and to be a reflection of the community. One of the issues with nonprofits is that they tried to tell communities what they need so we wanted the community to be reflected within the board,” Yousief tells Egyptian Streets.

Elmahaba started off with three core values; culture, community, and care, along with the aim to ‘heal’ the Coptic community.

“It was no longer sustainable to continuously be relying on a church that’s not offering services, and then to be hateful towards your own members,” she adds.

This is what led the values of Elmahaba to be to respect culture, to build community, to provide care. When volunteers come in, the board ensures that they understand the culture that they’re approaching, even if they’re Egyptian. Yousief also personally interviews every volunteer to make sure that they are ready for their responsibilities.

The Coptic Community in Nashville is one of the last of the largest immigrant communities in Nashville to have a secular facing organization that is independent of the church, Elmahaba Center. The Kurdish community in Nashville has a secular organization alongside the mosque, and the same applies to the Ethiopian, Somali and Latinx communities.

Weekly Live Streams Gather the Community

Check out our YouTube video with Ms. Mary Mesiha, LCSW, on love and respect in marriage from last week!!

Posted by ElMahaba Center Nashville المحبة سنتر ناشفيل on Tuesday, March 23, 2021

Elmahaba started off their Thursday live streams once a month, with board members coming in and giving advice since in March 2020 there was no information for Arabic speaking people about unemployment and COVID, and how to manage through the pandemic.

“We’re a very small organization. It’s me, four board members, and about 20 volunteers. All of a sudden, we found that Iraqis, Yemenis, Syrians were also attending these live streams, because they needed to know how unemployment worked, or how to apply for the loan that the federal government was offering the small businesses. So we began to do it every single week, as an update surrounding COVID-19 regulations by the state, and it kicked off from there,” Yousief shares.

Yousief describes the weekly Facebook live streams as a cultural moment. The live streams are for community news, support for those opening up new businesses, those struggling, and those who have an issue and want to present to the community for support. There is also an obituary, “it is an oral message board.”

On a recent community live stream, the issue of increased rates of divorce due to the pandemic came up.

“A Copt posted ‘we need to bring someone who can discuss counseling’ and the two board members who were running it said ‘we’ll bring a priest and we can discuss this with him and we can ask him about marital counseling.’ I thought ‘there’s no way we are going to bring a priest to discuss marital counseling, divorce, and parenthood.’ He’s an engineer by training who chose to become a priest. We are not going to feed into that mentality continuously that whenever there’s an issue, you need to go to the church,” she adds.

“The church is a spiritual mother. She is not the catch-all.”

Yousief tried to find a professional counselor to help advise on the issue but she could not find one that spoke Arabic in the area, which was another reason the community craved growth.

Growth of Elmahaba

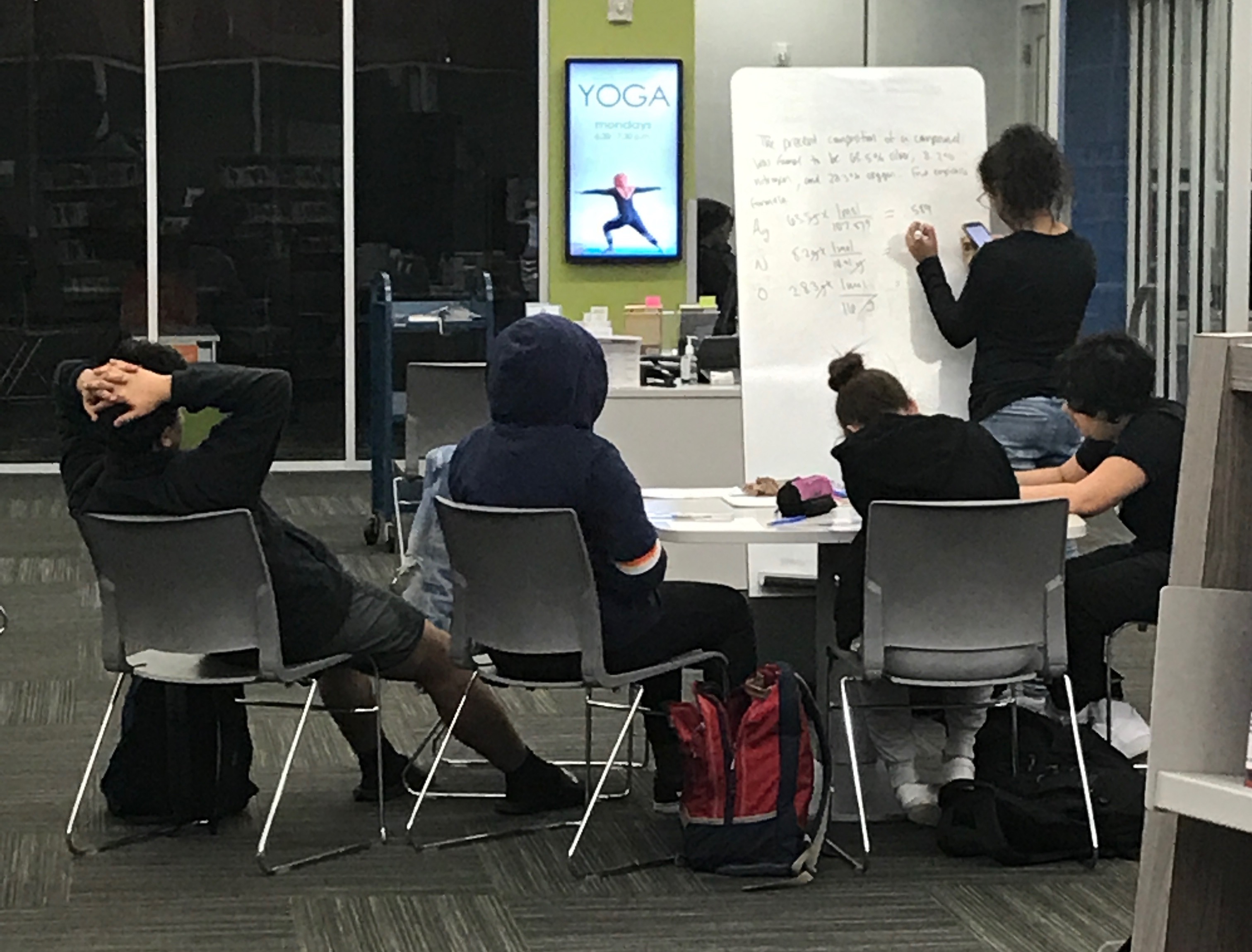

To tackle the education gap in Nashville’s Coptic Community, Elmahaba started with offering an ACT Exam (a standardized test used for college admissions in the U.S.) preparatory class, after finding that the ACT Exam was the easiest way to tackle the issues students face when applying for financial aid and searching for scholarships.

“The ACT, that’s how the easiest scholarships come through, and parents would come up to us and say, my kid has issues with essays, or with chemistry. So we started our tutoring program just before the pandemic hit,” Yousief says.

College student Nardien Sadek is a tutor and one of Elmahaba’s current. She studies Legal Studies, and is hoping to go to law school.

“Lydia was my high school servant [coptic church position] when I was going to church, and she was also my fourth grade Tasoni, and the only one I had that spoke English, and I’m really bad at Arabic. So that was really important to me because I want to feel like I’m being understood and she was the only one that actually understood me,” Sadek shares.

Later when Yousief started Elmahaba center, she asked for volunteers and Sadek volunteered to teach.

“I recruited some of my friends, and we started tutoring every Thursday in the library. Immediately, I just felt a connection to what she was doing, because it was so new and so beautiful,” Sadek tells Egyptian Streets.

“She would go out of her way to find people that needed help, offer her resources, offer time, her home, her car. Nothing screams service like someone that’s so willing to put their own time, money, and energy into something that they’re not getting paid for. I’ve worked in Elmahaba for at least three years now, which I’m very happy about. It’s an amazing organization.”.

Sadek contributes to Elmahaba as a tutor and especially from a mental health perspective. She has most recently been tutoring an eighth-grader with dyslexia and is helping him access the educational resources he needs.

“We also do something called Girls’ Talk, it’s a group of girls that come together and talk about mental health issues and social issues and things in our culture that we don’t like, or things that we feel we can’t talk about,” Sadek adds.

More American Than Egyptian

For Sadek, as an Egyptian-American who has spent her entire life in Nashville, her only “real connection” to her Egyptian identity other than her parents is the church, as it is the only place that resembles an image of Egypt for her.

“I feel extremely American. So, when it comes to Egyptian things when I go to church or interact with other Egyptians, it’s very difficult for me because I don’t understand the culture that much and everything points to me being an outsider. At the same time, it motivates me to, get more involved in my own footprint, and understand a little bit more about why they are the way they are,” Sadek says.

Sadek has noticed that people care where the other is from within Egypt, and the disparity of Egyptian dialects in the community was also a source of discrimination, with some having weaker Arabic, some having weaker English, and some with either Upper or Lower Egyptian dialects.

Yousief adds that the majority of the community is from Upper Egypt, so there’s always Se’edi (Upper Egyptian) jokes.

“The Northerners say the southerners are the ones that are bringing us back, or the southerners are backward,” Yousief adds.

“People will say this about each other and it’s very unhelpful language.”

Community Saturdays Begin to Impact

In 2021, Elmahaba received many requests from people asking for food, heaters, and clothing. Many newcomers from Egypt don’t arrive with proper winter jackets which are needed in Nashville where the weather can reach down to -17C.

That is when Elmahaba started their Community Saturdays in South Nashville, where people can donate new or used materials they have, ranging from strollers and car seats to jackets and toys.

“It’s been a very warming experience to see kids who stop by and get toys. We also have a lot of people who are not Egyptian. We have Somalis and a lot of Latinx people who stopped by as well, so I’ve had to learn some Spanish. It’s a very interesting time for us to,” Yousief shares.

Youstina Saber is one of the volunteers who helps Elmahaba with Community Saturdays.

“We pack breakfast meals, and we pass them out to the homeless, and we have multiple drives open, like the clothing drive, and if people have furniture that they need to donate to, newcomers. I just help out with as much as I can in all those fields,” Saber tells Egyptian Streets.

Saber is currently a high school senior. She moved to the U.S. from Egypt in 2008, when she was only four years old.

“I haven’t gone back to Egypt, except once. I’ve lived here my whole life. I really miss Egypt. I want to become a pediatric oncologist and I hope to open my own branch of nonprofit hospitals all around the world, to help Egypt, Haiti, and Kenya. I definitely do want to go back and help my own people, because I just have a connection there. No matter what happens, even if I’ve lived here my whole life, I still just have a major connection with my hometown,” Saber shares.

Saber’s parents own a pizza shop on the edge of Smyrna, a town near Nashville that welcomes diverse people from the area.

“It’s a pizza and pasta place. When we came here, at the very beginning, it was a rough start, because we couldn’t speak English, and we didn’t know many people here, but my dad’s goal was always to own a restaurant, and currently, he dreams of opening his own restaurant of cultural foods, because Baba is a great chef,” Saber shares.

While Saber and her family speak Arabic at home and are very much in touch with their Egyptian identity, she shares Sadek’s sentiments of being “Egyptian at church, American at school”. The dual identity, however, motivates Saber to prove others, who feel that because she wasn’t born in the U.S. she is less, wrong.

“I find it an opportunity to teach them and help them grow as well. Egyptian culture is everything. I never forgot my Egyptian culture, because my grandma lives with us and my parents made it really obvious that they never want us to forget. My dad does not allow English at home, because he doesn’t want us to ever forget it,” she shares.

In elementary school, Saber remembers feeling different looking around at her white classmates with blonde straight hair and green eyes.

“It was upsetting at first because you think, ‘I don’t look anything like these people.’, Saber adds.

“Now, I’m really proud of who I am, and with my siblings, I teach them that you’re different and that’s perfectly fine. That’s something we try to emphasize a lot in church serving the little kids.”

Elmahaba’s Vision for the Future

In 2021, Elmahaba’s goal is to acquire physical space for its activities, including Community Saturdays. Every Thursday, there will be a lawyer there who speaks Arabic, and every Friday there will be a doctor at an office there, and every Saturday, there can be lectures about Egypt.

“Our ultimate goal is to become a community center, with the bottom level being businesses, and the top-level being services is very important to me. To be a place that celebrates our culture and allows people to be who they are,” Yousief says.

“Our cultures in Egypt, in North Africa, and Southeast Asia are all very beautiful cultures, and there’s no reason to abandon them, because the government doesn’t like them, or white society doesn’t like them.”

Yousief dreams of an Elmahaba in 20 years that is a very big community space in Nashville to reflect the 20,000-30,000 population of Egyptians in Nashville.

“We’re not on the map at all, and what’s worse is that many people in Nashville don’t know that either. We have 10 church buildings all with huge staples. No information whatsoever about who these people could be, so having a huge building that centers our cultures from Iraq to Egypt and elsewhere, is very important to me,” says Yousief,

“But of course, that’s 20 years in the making.”

Comments (2)

[…] Elmahaba Center: Uniting Coptic Egyptians in Nashville’s Little Minya […]

[…] Elmahaba Center: Uniting Coptic Egyptians in Nashville’s Little Minya […]