Today, Coptic Christians in Egypt and beyond are celebrating Coptic Easter Sunday, one of the most important events in their religious calendar. Many across the world may simply associate Easter with cartoon rabbits and chocolate eggs, but for the Christian population of Egypt, Easter Sunday is a cherished celebration rooted in centuries-old tradition.

Coptic Christianity and its rich and deeply historical customs have faced many challenges over the years, but since the beginning of 2020, a new threat has emerged: COVID-19. This year, worshippers are again forced to adapt how they engage with their faith to the incredible circumstances sweeping the world, while still upholding the ceremonies and celebrations which they hold so dear.

FROM A MAJORITY FAITH TO A DWINDLING MINORITY

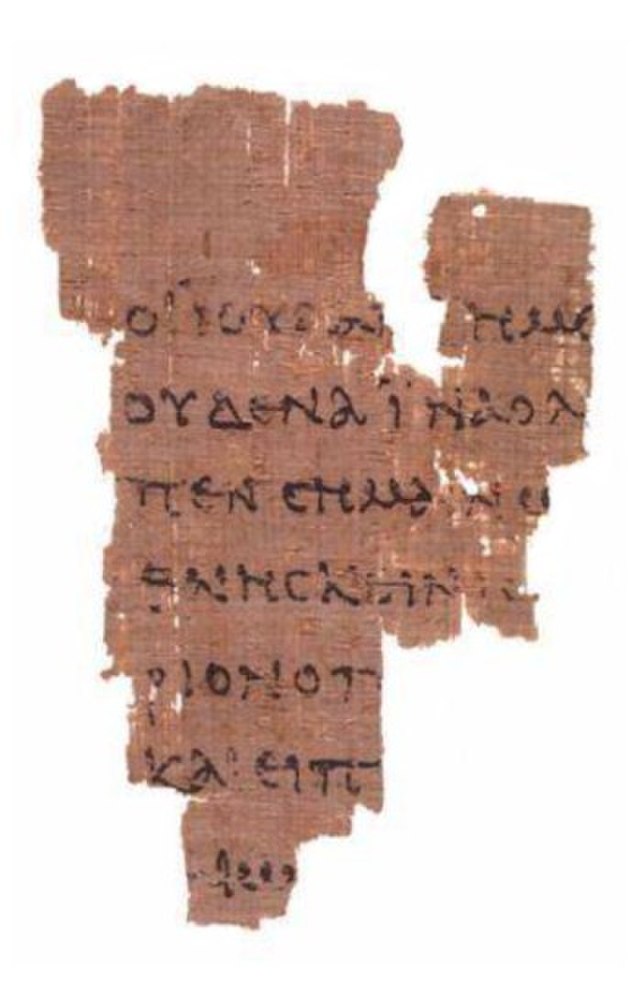

According to ancient tradition, Saint Mark’s arrival in Alexandria in the first century marked the introduction of Christianity to Egypt, in the midst of the rule of Roman emperor Claudius. The religion spread far and wide, clear from the discovery of a fragment of papyrus in Upper Egypt with Saint John’s Gospel written on it in the Coptic language, which is said to date back to the second half of the first century. The Church of Alexandria formed as the oldest Christian Church in Africa and Christians constituted the majority of Egypt’s population by the beginning of the third century.

This majority status continued for centuries until the 1400s where significant persecution, along with other socio-political and cultural issues, caused the scale of traditional celebrations and worship to dwindle. Today, Coptic Christians are estimated to represent between five and twenty percent of the Egyptian population.

THE HOLY WEEK

Coptic Easter commences with Palm Sunday, which commemorates Jesus’ arrival into Jerusalem prior to his crucifixion. Many purchase palm from street sellers and carry them through the streets to symbolise those that were thrown at Jesus’ feet as he rode through the streets of Jerusalem.

Other notable days in the Holy Week include Maundy Thursday which notes Jesus’ last supper with his disciples before he is betrayed by Judas, Good Friday, on which his crucifixion is remembered and Holy Saturday, the day before Easter Sunday.

Throughout this week, Christians attend prayers, read in Arabic and Coptic, whilst continuing their Lent fast, which they undertake for the 55 days prior to Easter Sunday. All animal products are avoided, and some additionally refuse fruits and desserts during the Holy Week.

This tradition culminates on the evening of Holy Saturday, where worshippers gather to break fast after a day of prayer. This Easter Eve also involves “resurrection plays”, re-enactments of Christ’s ascension, which are rife with symbolism – lights are turned off to represent the darkness that humanity lived in before the coming of Christ, and turned on again to show his opening of the gates of heaven upon his ascension.

Coptic Easter Sunday marks the official end of the Great Fast, and symbolises the resurrection of Christ. Families eat banquets together, enjoying meats, fish, biscuits and fatteh – spiced meat served over a bed of rice – to celebrate, and often wear new specially-bought clothes.

The final day of the Holy Week is Easter Monday, or Sham El-Nessim. This national holiday has been celebrated by all Egyptians since the formation of the Arab Republic of Egypt in 1953 but is known for its links to Coptic and ancient pre-Christian traditions. The origins of the holiday date back to 2700 BCE during the Pharaonic era of the Old Kingdom, where the arrival of Spring was celebrated. It originally fell in the middle of Coptic Christian’s Great Fast, so celebrations were moved to the day after Easter.

In modern times, Sham El-Nessim has been fully integrated into Coptic Easter, but traditions such as eating salted mullet, green onions and lupin as well as colouring eggs are said to have originated from ancient Egyptian celebrations of fertility, despite also having connotations with the resurrection of Christ.

EASTER AND COVID-19

Last year’s emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic spun these centuries-old traditions of worship, feasting and communal Church services into disarray. Easter 2020 was a Holy Week like no other for the Coptic community – for all the wrong reasons. Amid the national shutdown, a ban was placed on religious congregations in Egypt’s places of worship, such as churches, to slow the spread of the disease. For the first time in living memory, these ancient traditions were unobserved with important worship and celebrations reduced to largely solitary events.

With the pandemic’s disruption and destruction ongoing, it comes as no surprise that 2021’s celebrations are also far from normal. It was announced in April that 18 dioceses across Egypt will suspend services during this year’s Holy Week and Easter as part of efforts to contain the spread of the novel Coronavirus. In some cases, Mass has been prohibited, and in others attendance will be capped at 25 percent. It was further announced by the government that public parks and beaches will be closed on the day of Sham El-Nessim to prevent large gatherings amid a rise in COVID-19 cases.

Coptic Easter, like many religious celebrations, is characterised by participation by the collective – whether it be through busy Mass services, breaking the Lent fast with family, or sharing fesikh in public parks. COVID-19 restrictions have only highlighted this further, as the celebrations take on a more bittersweet tone, rather than one of communal joy.

Whilst Christians across the nation celebrate in a more scaled-down fashion, many have hope for the future, where such historically-grounded and treasured traditions can once again be enjoyed to their full extent.

Comment (1)

[…] U moderno doba, Šam El-Nesim je u potpunosti integrisan u koptski Vaskrs, ali se kaže da tradicije kao što su jedenje slanog cipala, zelenog luka i lupine, kao i farbanje jaja, potiču iz drevnih egipatskih proslava plodnosti, iako takođe imaju konotacije sa vaskrsenjem Hristovim, piše “Egiptian Streets”. […]