“Cycling is possibly the greatest and most pleasurable form of transport ever invented. Ride through a city and you can understand its geography in a way that no motorist, contained by one-way signs and traffic jams, will ever be able to.”

With this quote, Heba Attia’s blog Tabdeel welcomes you into her world of urban design and “artivism” (art activism). Tabdeel, which can be translated to the verbs “pedaling” and “change”, is an initiative to create cleaner, healthier and human-centred cities in Egypt and North Africa.

Heba founded Tabdeel in 2018. She had just completed a master’s degree in Urban Development in Germany where she had discovered her love for cycling. Returning to Egypt, her choice of using a bicycle as a mode of transportation was met with resistance and confusion.

“In Egypt, cycling has a specific image: it’s either a cool sport for young fit men, or a mode of mobility for poor people who cannot afford anything else”, Heba tells Egyptian Streets. Neither of these perceptions leave space for a young woman to cycle to work in the morning without being bothered by strangers in the street.

“It made no sense to me, because biking is so much more convenient compared to public transportation”, says Heba. Not wanting to give up cycling, she decided to change people’s perceptions and challenge socially constructed gender and class limitations.

Collectively re-designing the streets of Egypt

Holding a BA in Architecture, Heba wanted to find out how to make Egyptian urban landscapes more bicycle friendly. She organised a series of public workshops, initially in cooperation with the Bibliotheca Alexandrina, and invited residents of various Alexandrian neighbourhoods to come together and discuss public urban spaces.

These workshops informed design processes which she eventually turned into proposals, collectively written by architects, sociologists and business designers. Heba submits these intervention proposals to the government and brings them in conversation with the communities that informed them. In Alexandria, she turned them into a design exhibition at the Bibliotheca, which invited people to imagine what it would be like to cycle around Alexandria through a VR simulation model.

“We made a survey to see whether the people would like to have such an infrastructure by the corniche, and to know what they want to change. It was important to use the VR simulation so that those who do not know how to cycle also get a say”, Heba explains.

Afterwards, the proposal was submitted to Alexandria’s governor. Tabdeel is now working with governmental authorities to create Egypt’s first legal code for designing streets that accommodate cycling.

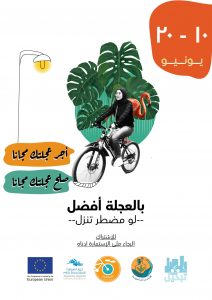

Advocating for women’s freedom of movement

In addition to their work on redesigning urban infrastructures, Tabdeel also runs advocacy and research projects. The organisation collects data on bicycle use across Egypt, verifying that most people cycle in Asyut, Sohag and Port Said. However, outside the centre, women face more limitations. Originally from Hurghada, Heba tells of the obstacles women face in smaller towns.

“I never cycle in Hurghada, not even now”, she says. “It’s very challenging, because the local community is conservative and there are many wrong assumptions about women who cycle.”

She mentions the stigma around biking and virginity – a common fear that biking will break a girl’s hymen – and the general perception that a woman’s posture looks “too sexy” on a bike.

These stereotypes are increasingly challenged through groups for recreational cycling. Women usually feel safer riding their bike in a group, because it makes traffic easier to navigate and helps them to avoid being catcalled.

“It’s important that we see women biking in the streets, especially hijabi women”, Heba explains.

Heba’s hope is that once women feel comfortable cycling in groups, their next step will be to cycle solo and for mobility purposes. Apart from social obstacles, there is a general lack of availability, because the market mostly produces bicycles for “fit men”.

“Most bikes are for sports, not for commuting. I could not find a bike my size, so I had to take a bigger one and just get used to it.” To address issues of accessibility and diversity, Tabdeel recently launched a cargo bike sharing initiative, which is donation based and allows people to rent a bike for a day.

Is a car-free Cairo possible?

Tabdeel is also part of the Carfree Cities Alliance. According to Heba, only 10% of the Egyptian population own cars. Still, cities are oriented towards accommodating cars rather than human mobility. Heba highlights the Cairo neighborhood of Nasr City as an example for car-centrism, while many streets in Old Cairo are basically car-free. The urban design of Cairo’s neighbourhoods varies greatly and Tabdeel invites bikers to explore the different areas and street layouts.

“Cairo won’t be car-free anytime soon”, Heba admits. “But what we can do is orient urban design towards modes of mobility that include public transport, walking and cycling, rather than focusing on fitting x number of cars into a city that is already so dense.”

Cycling Culture Artivism and the question of climate change

Outside of Cairo, Tabdeel cooperates with various initiatives to combat class stigma around cycling. “Many people cycle outside of Cairo, but mainstream culture makes them want to upgrade to cars and scooters”, explains Heba. Recently, they teamed up with Arte Vision Africa to create graffiti art in public schools.

“I wanted to talk about mobility and address the growing tendency that teenagers consider biking not cool”, Heba says. “We used art, because it gets to the emotions. People don’t speak statistics.”

In a school in Asyut, students were invited to reimagine a local art form related to a fabric called tully. Traditionally, artists use needlework to form abstract shapes in imitation of the environment on the tully cloth. The students created graffitis in that style and added bicycles to their environment, inserted into depictions of the Nile and their school. These workshops were intended to raise conversations around climate change, introducing cycling as a green mode of transport.

Heba’s love for biking has inspired her to address topics such as climate change, class and gender in Egypt and beyond. She tells of others who work on similar projects in Ethiopia and Kenya, and the connections Tabdeel has made across the Arab world. As part of their advocacy work, they create Arabic content about cycling urbanism, through translating books and documentaries.

“Change happens in cities first. Women usually find spaces to push boundaries, and then it can also happen outside,” Heba says. For example, it is now normal in Alexandria for women to ride electric scooters. “They found a way to change the culture”, she says, smiling hopefully. Next up are bike friendly streets and communities.

Subscribe to the Egyptian Streets’ weekly newsletter! Catch up on the latest news, arts & culture headlines, exclusive features and more stories that matter, delivered straight to your inbox by clicking here.

Comments (0)