Photo via Marina Makary

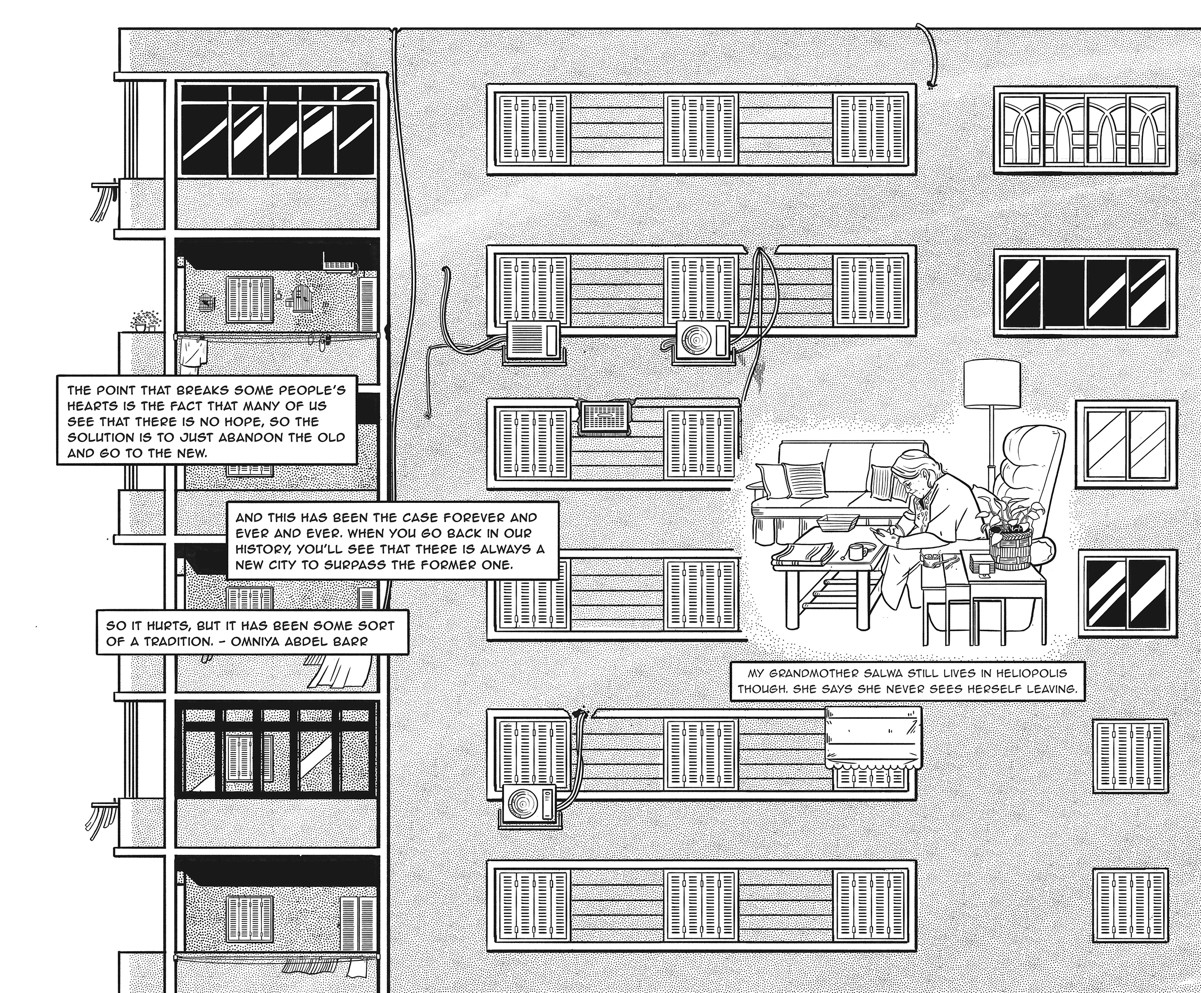

“My grandmother’s living room in Heliopolis is one of my favorite places in the world,” says 24-year-old Nora Zeid, with a big smile on her face.

In her efforts to reconnect with her hometown, specifically Heliopolis where her parents grew up, illustrator, designer and visual artist, Nora Zeid created black and white illustrations of Heliopolis, tying memories and personal experiences to space and addressing the idea of honoring heritage in line with the current infrastructural changes.

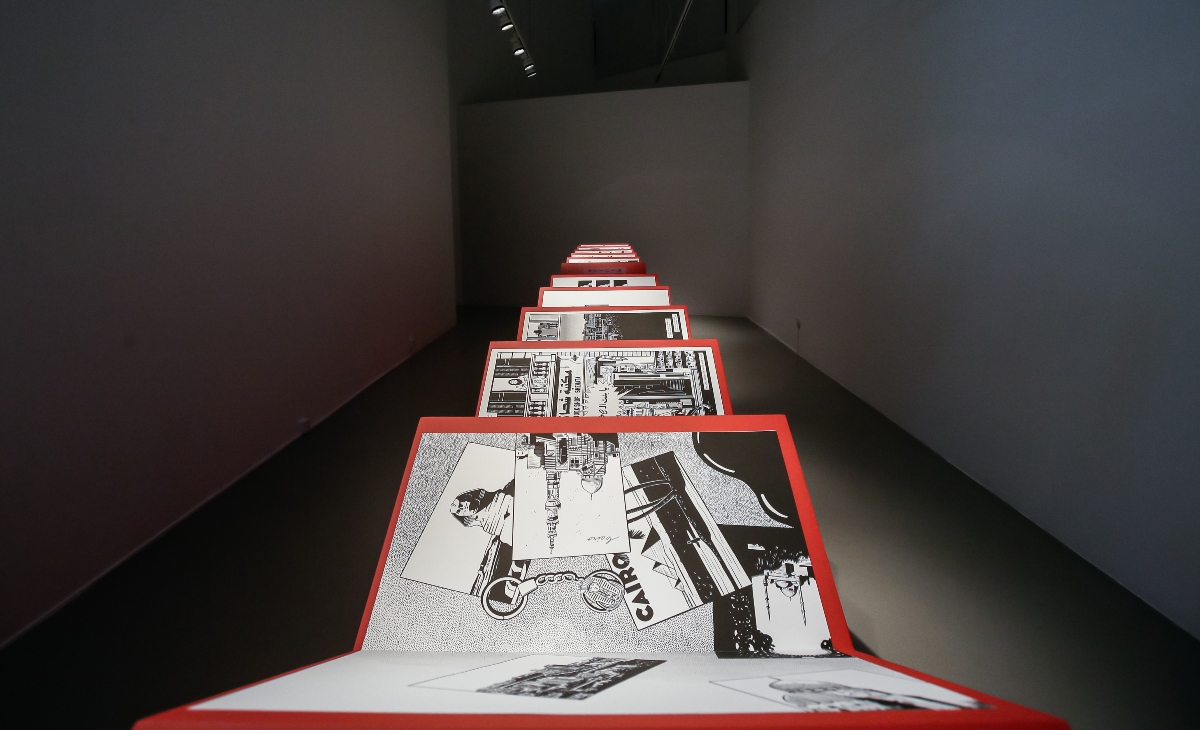

Cairo Illustrated: Stories from Heliopolis is Nora’s first solo exhibit under Tashkeel’s Critical Practice Program for 2020, under the mentorship of Hala Al Aini, lecturer at the American University of Sharjah and Co-Founder of Möbius Design Studio, and Ghalia Elsrakbi, prominent design professional and researcher.

Egyptian Streets sat down with the young Egyptian artist, where she took us with her on her journey towards reestablishing her relationship with her hometown.

Photo via Marina Makary

“I grew attached to Cairo in 2017 when I stayed at my grandmother Salwa’s house. The living room was one of my favorite places because I didn’t like going to Cairo very much growing up; it was very different from where I was growing up. It was busy, and there was traffic; I like quiet places, so it was challenging for me to be in Cairo. But then when I saw my grandmother was able to have a quiet life, even though she lives in one of the busiest cities in the world, I was like, okay, Cairo is more than just a busy city,” she narrates.

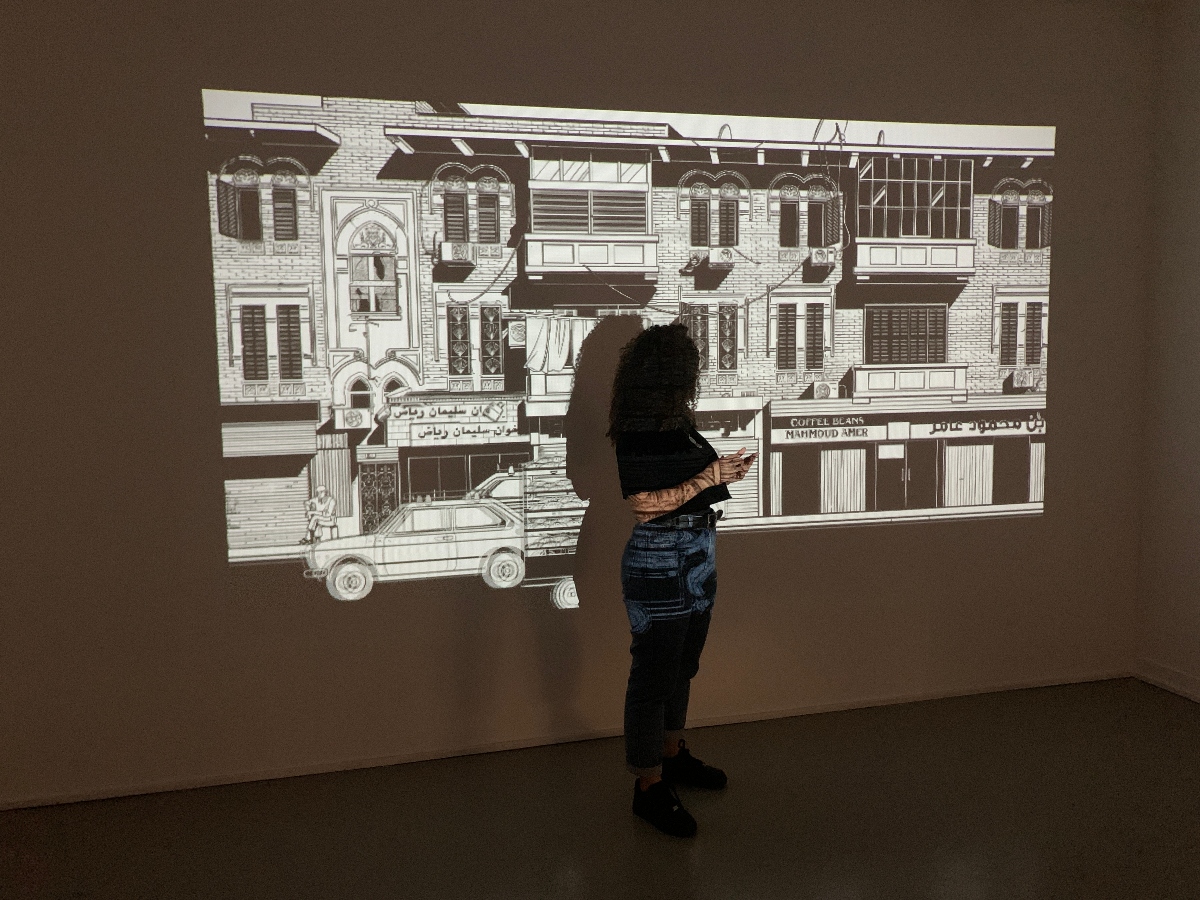

It is common among artists, designers, and illustrators to struggle to find their own style, or tell a story in their own unique way. In Cairo Illustrated: Stories from Heliopolis, Nora chose to stick to black and white illustrations to blend simplicity of color with complexity of the bustling streets of Cairo. She describes her illustrations as “freezing a moment in time so people can take it in”.

Why Heliopolis?

Despite being primarily based in Dubai, Nora does retain a special connection with Heliopolis. “My first drawing classes were in Heliopolis,” she says cheerfully.

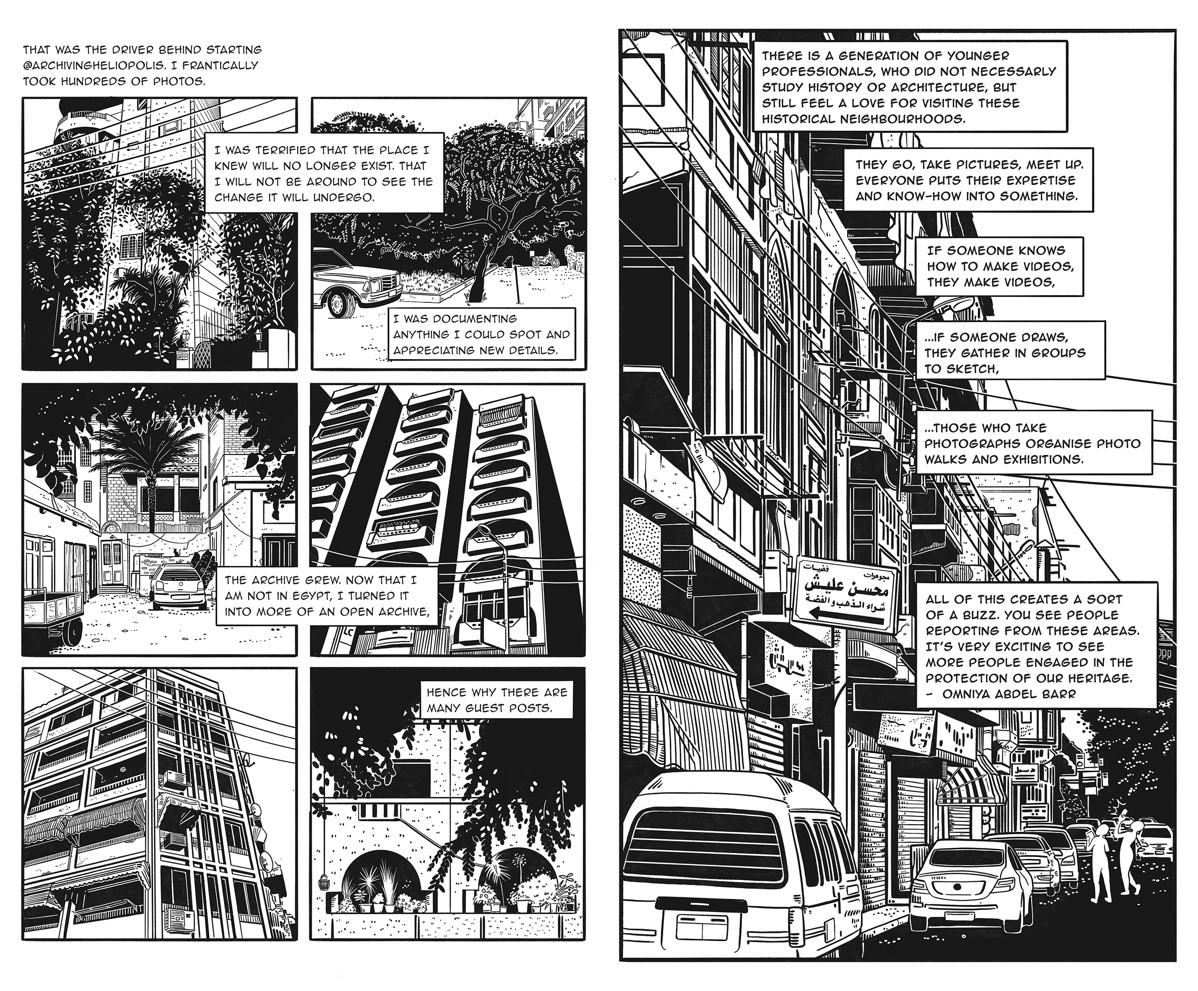

Because Heliopolis is currently one of the areas in Cairo that is undergoing drastic changes in terms of infrastructure, Nora thought it was important to tackle what people view as heritage and what they deem as valuable.

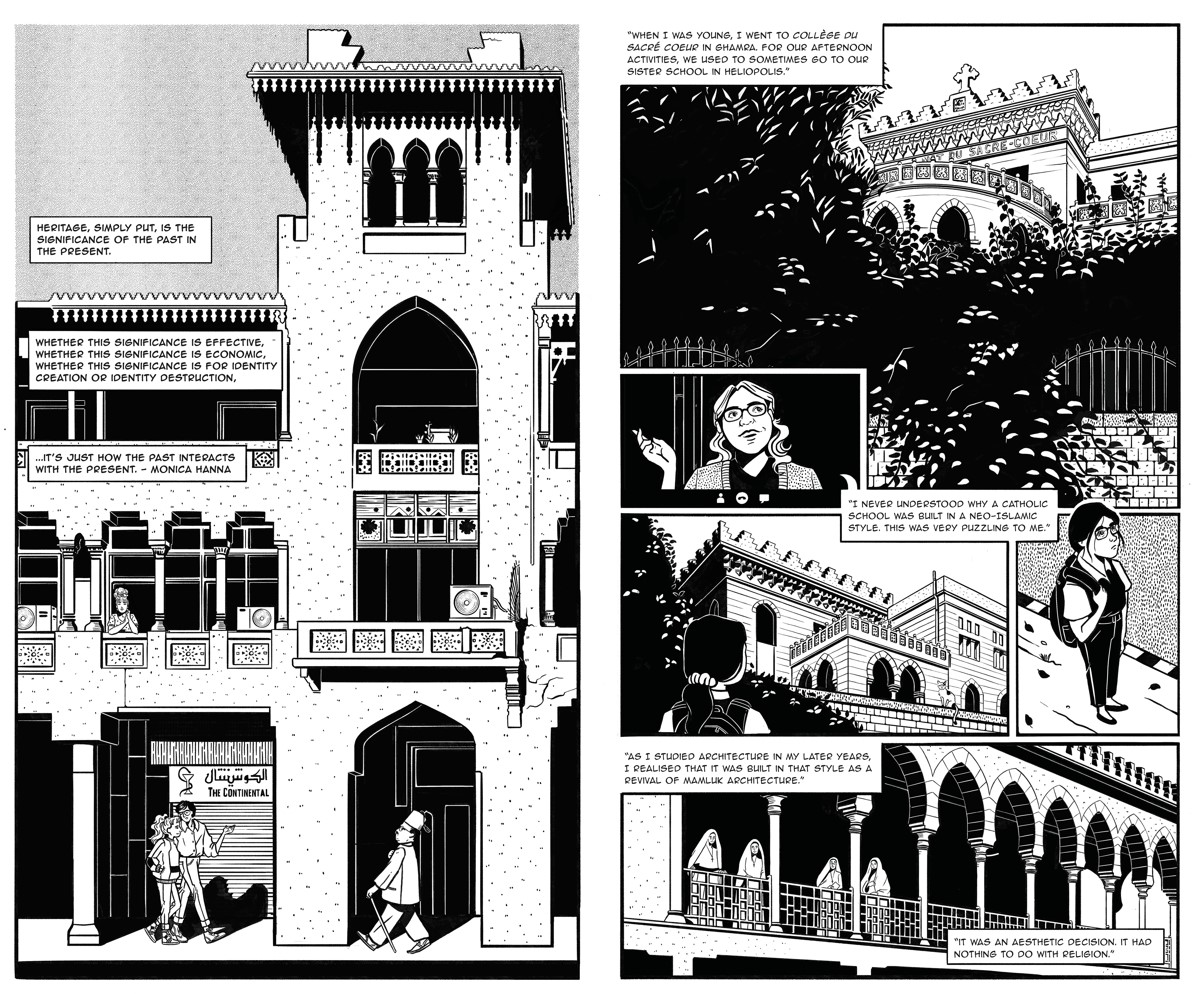

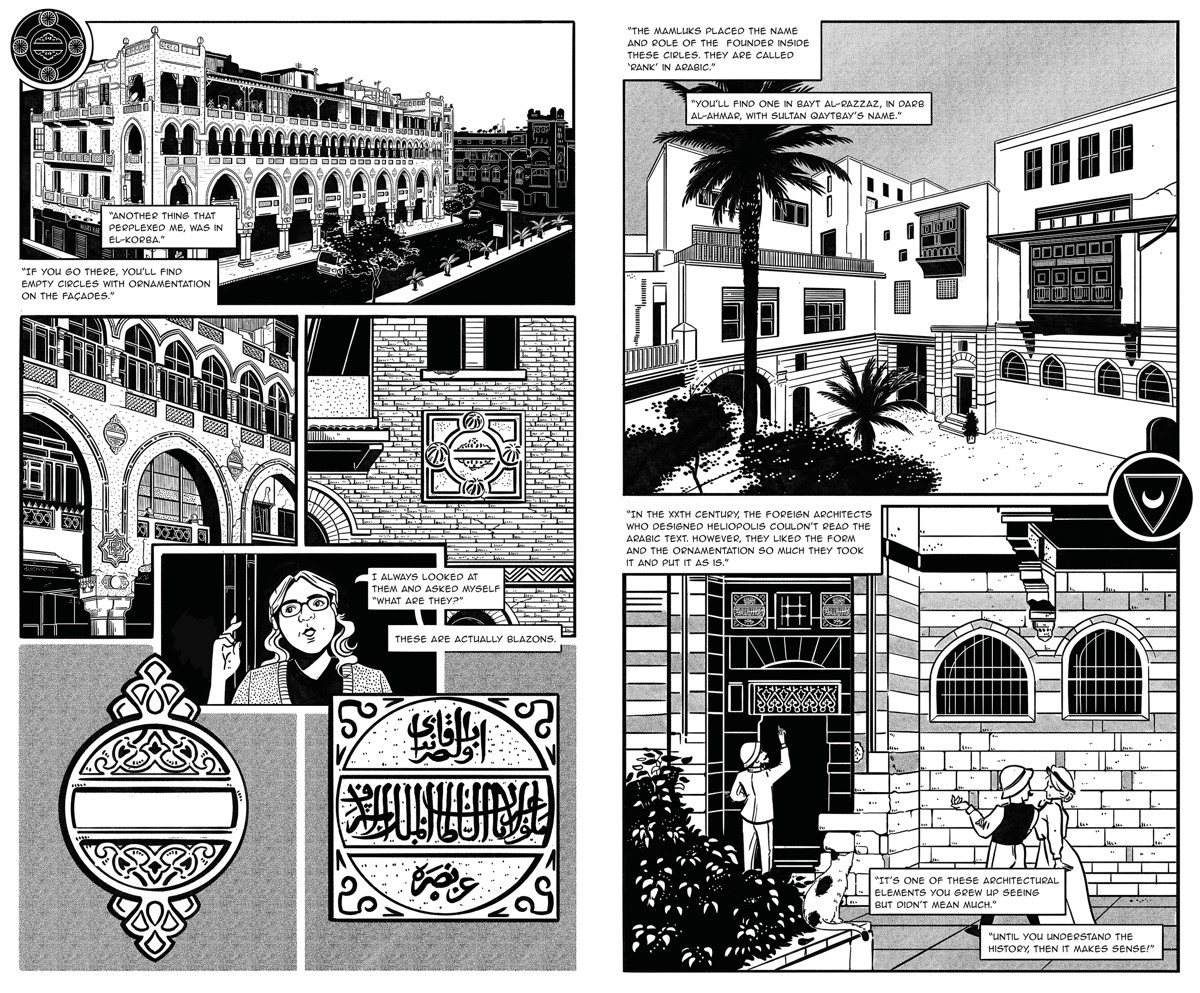

Referred to as Masr El Gedida in Arabic, Heliopolis is known for its distinctive French-style buildings and Islamic architecture. While the history of the now-bustling residential area is not commonly known, dwellings in the area date to predynastic times (circa 3,000 B.C.), rendering it one of the country’s former oldest cities. Overtime, it became a regional center for the worship of the sun-deities during Dynastic Egypt, hence the formation of its name ‘city of the sun’ (helio-polis).

In the last two years, Heliopolis has seen distinct changes prompted by governmental decree: trees were cut down, streets were widened, and Korba’s tram tracks have been gradually removed. Accordingly, many of its residents complained that making significant changes to the urban design of Heliopolis to widen streets and build bridges to allow a larger traffic flow, and connect the district to main highways is removing the district’s uniqueness and personality.

Ultimately, like many other suburbs, Heliopolis became a part of Cairo and no longer an escape; Heliopolis itself was originally built 13 kilometres ‘outside’ of Cairo. Nora comments on the way the new compounds today are marketed the way Heliopolis was marketed decades ago.

“We left Masr El-Gedida (New Egypt) for New Cairo. So, we left the suburbs for the suburbs of the suburbs because the suburbs are no longer suburbs,” adds Nora. In its own way, her exhibition reflects on the idea of people constantly “escaping the old and moving to the new” particularly in a city like Cairo, whose residents have been noted to leave to newer areas such as Tagamou’ (Fifth Settlement, East) and 6th of October (West).

How do we value our heritage?

Nora highlights that Egyptians often value their heritage through the eyes of a foreigner, by constantly linking it to tourism. Other times, they consider older monuments and heritage sites as more valuable than modern ones.

Through her exhibition, Nora aims to challenge people’s definitions and perceptions by exploring the question “How do we value our heritage?”

The exhibition starts with a spread of illustrations that shows a typical view of the mainstream understanding of Egyptian heritage in Cairo: mainly mosques, the pyramids, the Sphinx and the Nile. Following which, she shifts to images of postcards and souvenir shops that one can expect to see at any street corner in Cairo, and later to personal and relatable memories of residents or visitors of Heliopolis.

Apart from the postcards, streets, buildings, and shops, Nora includes many illustrations of windows in her story.

“Up until last year, I only experienced the city through windows: the window of the plane, the car window, or the window of the balcony of whatever relatives we were visiting at the time,” she explains.

Despite having spent some time in the past in Heliopolis, Nora interviewed people who lived or visited Heliopolis regularly, about their thoughts on what they consider as “heritage”, as well as their memories in Heliopolis.

Photo via Tashkeel

These people were Mahy Mourad, a Cairo-based architect and researcher, Omniya Abdel Barr, architect specialising in cultural heritage conservation and documentation, Monica Hanna, Aswan-based Egyptologist, Marwan Imam, Filmmaker and co-founder of online content creation company Peace Cake, Salwa Hedayat, Nora’s paternal grandmother, and the admin of @archivingheliopolis. Nora’s exhibition unfolds through intimate memories and expert commentary from these characters on their relationship with Heliopolis.

Standing by the last spread in the exhibition, Nora explains that she does not define herself as an animator, yet, she often animates to “give life to her illustrations”.

“I wanted to capture people who are moving in the streets, the cars, trucks, the man selling bread etc. to show that you cannot separate the local communities of an area from the area itself, and that both need to be considered together,” she explains.

“A lot of times in conservation efforts, local communities are excluded or they’re disregarded, and I understand that people want to prioritize the buildings and the spaces physically, but these communities are equally part of our heritage, and they need to be considered because they are the ones who live in these areas, they’re the ones who know it best, and they’re the ones who will be able to take care of it best.”

The exhibition runs from the 14th of September to the 23rd of October at Tashkeel art center in Dubai.

Photo via Tashkeel

Subscribe to the Egyptian Streets’ weekly newsletter! Catch up on the latest news, arts & culture headlines, exclusive features and more stories that matter, delivered straight to your inbox by clicking here.

Comments (4)

[…] هذه الرواية الكلاسيكية التي لا يمكن إنكارها عام 1932 هي عنصر أساسي في الأدب البائس. على الرغم من أن فكرة المستقبل حيث يتم تربية الناس وتلقينهم اجتماعيًا تبدو وكأنها كليشيهات ضمن هذا النوع ، إلا أنها كانت رائدة في وقت نشرها. يظل الحديث الساخر عن المدينة الفاضلة المتقدمة تقنيًا كلاسيكيًا حتى يومنا هذا. هذا الكتاب أوصى به نورا زيد. […]

[…] An undeniable classic, this 1932 novel is a staple of dystopian literature. Though from a current perspective the idea of a future where the people are bred and socially indoctrinated sounds like a cliché within the genre, at the time of its publication it was groundbreaking. The satirical telling of a technologically advanced utopia remains a classic until this day. This book was recommended by Nora Zeid. […]