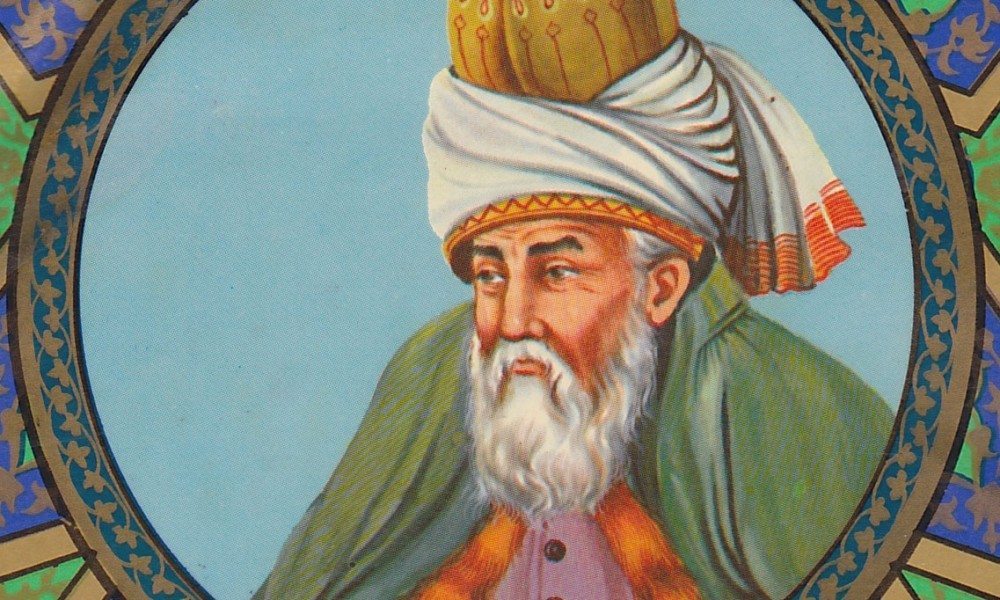

A poet, a mystic, and mawlana: Rumi is a name most postmodern scholars have come to associate with Persian lyricism and philosophy. To the Western world, he is the face and father of Middle Eastern literature; a man so versed in language and rhythm that dyadic epics bent to him.

To many, Rumi is a Sufi first: always in the graces of divinity and worship, circling his writings back to Islam’s more niche thought avenues. Sufism, Rumi’s primary ideology as a theologian, is a branch dedicated to the “mystical expression of the Islamic faith,” laden with values of asceticism, prayer, and a profound appreciation for creation in all its forms.

To most, however, Jalal al-Din Rumi is an enigma: he is an odd poet who – by the grace of fortune and skill – managed to restructure mystical thought and literature throughout the Muslim world.

Early Life

Born in 1207 Afghanistan to established mystical theologian, author, and teacher Baha al-Din Walad, Jalal al-Din’s youth was fortified with language and religion. Stability, however, was a fleeting privilege; whether due to a dispute with the Afghan ruler or the onset of Mongol attacks, the family was made to flee their native Balkh cicra. 1218.

Long and arduous was the journey across the Middle East, and along the way, Jalal al-Din was both subject to struggle and salvation. Legend holds that, in Nishapur, Iran, the family met Farid al-Din Attar, “a Persian mystical poet who blessed young Jalal al-Din.”

Soon after completing the pilgrimage to Mecca alongside his father, the family moved westward, journeying towards Anatolia (i.e. ‘Rum’, where the surname Rumi is derived). Anatolia, what is more commonly referred to as modern Turkey, was a promise of peace and prosperity and served to offer Jalal al-Din just that for an onset of years.

After his father’s passing in 1213, Jalal al-Din took over his job of teaching at local religious schools, where he would become acquainted with Burhan al-Din Muhaqqiq. Soon after, Buhran al-Din became a key figure in his spiritual development and formation, introducing Jalal al-Din to several mystical theories he’d developed in Iran.

Shams al-Din of Tabriz

Like all great masters of language, Rumi had a muse: an untethered soul that embodied the holiest of worship. Shams al-Din of Tabriz, also known as Shams al-Tabrizi, was an undecorated man; a dervish who wandered the streets of Konya carrying with him the mysticism Rumi so ardently chased.

The divisive meeting came in November of 1244 on a Syrian street, and between their overwhelming, spiritual personalities, Shams and Rumi became largely inseparable. So inseparable, in fact, that their unorthodox closeness became cause for worry; in his blind infatuation with Shams, Rumi had neglected his family and disciples.

Until one night, only three years after their meeting, Shams al-Din of Tabriz vanished without a lingering trace or word of whereabouts. Shattered, Rumi turned to poetry; a soothing balm for the brokenhearted. It was only in the 20th century that scholars confirm Shams al-Din was murdered at the beck of Rumi’s own sons.

It was the love and fraternity between Rumi and Shams, however, that was the birthplace of his poetry–his ghazal: experiences of love, longing, and loss. His son remarked that “[Rumi] found Shams in himself, radiant like the moon.”

It’s this near achillian love that brought Rumi to his literary apex. In a collection named The Poetry of Shams, Rumi delineated the very intimate link between religion, love, and Shams al-Din of Tabriz.

Magnum Opus & Legacy

Rumi’s magnum opus, or more fittingly his most famous work, has been his didactic epic Mas̄navī-yi Ma’navī (“Spiritual Couplets”), “which widely influenced mystical thought and literature throughout the Muslim world.”

Through his use of Persian and Arabic, in addition to sparse Turkish and Greek, Rumi’s legacy has become intertwined with that of Iran and Turkey. His influence, however, remains substantial across the Middle East as a whole, stemming as far as the Indian subcontinent. By the late 20th century, Rumi cemented his fame worldwide, in a posthumous global phenomenon “with his poetry achieving a wide circulation in western Europe and the United States.”

Over the centuries, a separation has formed between his legacy as a poet and his long-standing study as a theologian. It is important to remember that between the lines of literature and Shams al-Din, remains a deeply influential religious figure – one that, to this day, is a pillar of Sufism and Muslim mysticism.

Comments (2)

[…] مولانا الصوفية: جلال الدين الرومي […]

[…] مولانا الصوفية: جلال الدين الرومي […]