To many people, eating a meal takes a small portion of their day. But to those who struggle with an eating disorder, the most basic act of eating is torture. Eating disorders do not only dismantle your relationship with food, but they deform how you treat your body.

The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) in the US defined eating disorders as “serious and often fatal illnesses that are associated with severe disturbances in people’s eating behaviors and related thoughts and emotions. Preoccupation with food, body weight, and shape may also signal an eating disorder.”

The eating disorder first comes as a wary visitor to individuals. A war is waged between their body and their thoughts. As time passes and the eating disorder further develops, it becomes a regular visitor. It often becomes a perceived source of comfort, it sits and feeds off of a person’s negative perceptions — always takes, and never gives.

Untick the Boxes

The American Psychiatric Association highlighted the categories of eating disorders: “types of eating disorders include anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder, avoidant restrictive food intake disorder, other specified feeding and eating disorder, pica and rumination disorder.”

At their core, eating disorders are incredibly complex, and it is often difficult to fit every person’s experience into a specific box. Eating disorders are not one-size-fits-all, hence, there is always the risk of oversimplifying or misdiagnosing them.

Psychologist Rita Kallini, alongside Psychologist Nayla Grace, explained to Egyptian Streets how eating disorders distinctly vary.

“It’s definitely not a ‘one-size-fits-all,’ diagnosis,” she explains. “The problem with eating disorders is that there is a big overlap between them, and the distinction becomes arbitrary. For example, anorexia and bulimia can look very similar at times. Eating disorders can be expressed in so many unique and individual ways.”

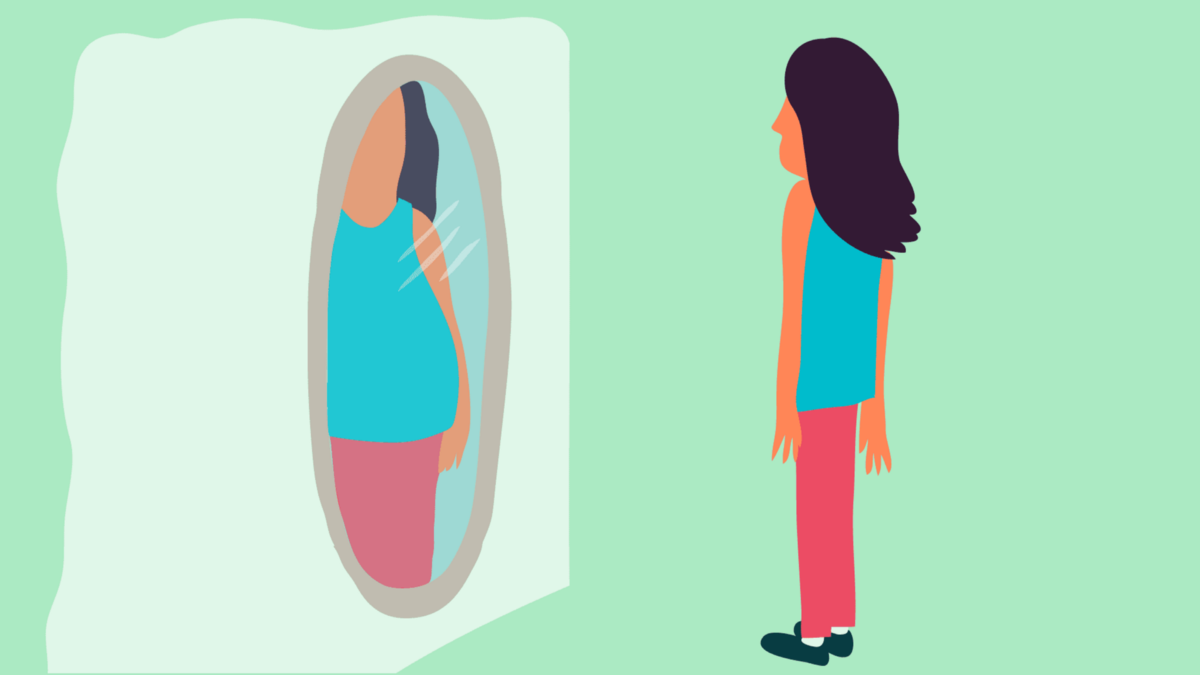

Living with an eating disorder extends beyond a distorted body image; it often exacerbates feelings of unworthiness and loss of control.

Myths and Misconceptions

The National Eating Disorder Collaboration, an initiative of the Australian Government’s Department of Health, identified certain myths about eating disorders. The myths include the distorted perceptions that eating disorders are a choice, a cry for attention, and that only women and girls are affected by eating disorders.

“One of the most common misconceptions is that eating disorders aren’t severe illnesses and that it’s not about the food,” Kallini expresses. “While there are so many others, I think that once it’s clear that eating disorders are serious mental disorders and occur due to severe underlying causes, it becomes clearer how many other factors contribute to their development.”

Eating disorders look different for everyone. Kallini reiterates some of the signs that could signal an eating disorder: For someone dealing with anorexia, the signs include significant weight loss, constant dieting, and excessive exercise. Bulimia nervosa signs include going to the bathroom after meals, spending long periods of time in the bathroom, and discomfort or reluctance to eat in front of other people. Although these signs differ distinctly from one person to another, there could also be other subtle signs that are hard to detect.

Such disorders markedly impact the quality of life of those who suffer, Kallini clarifies. She underscores that the extent to which eating disorders affect their victims depends on a number of reasons, particularly how long the person has had the illness.

“There is a lot of time that becomes devoted to food, controlling food intake, exercise gouging [explain what that is in square brackets], which can all have an immense impact on a person’s ability to fulfill their daily obligations. A person’s concentration, physical and mental health are easily affected as well, which can consequently have negative effects on a person’s day life,” she highlights.

The Cultural Dimension

There are unspoken rules, a secret language that only individuals who suffer from eating disorders understand. They often attempt to hide their disordered thoughts and behaviors, keeping it a secret from other people.

“With eating disorder sufferers, there is a strong sense of secrecy that comes with it. It often takes a person many attempts to keep the disorder private. With the influence of social media, this is starting to change, and I am hopeful that we can start to talk more about the seriousness of eating disorders,” Kallini expresses.

Egyptian psychiatrist Mervat Nasser authored a book called Eating Disorders and Cultures in Transition, in which she compared eating disorders in the Arab region and the Western world.

Her conclusion was that eating disorders do not only exist in Western countries, in fact, they also are prevalent in the Arab region.

Hania Ibrahim, a 22-year old student, shares her trials and tribulations of living with eating disorders in Egypt with Egyptian Streets.

Ibrahim grew up in an-all-women household, where different bodies and opinions were formed. She began realizing how different her body looked because she did not look like her rather small-sized sisters or the rest of the girls at her school.

“I was always thicker than other girls in my class. I was curvy and tall, and everyone around me was slim and small,” Ibrahim recounts. “I started questioning the way my body looked when I was six years old. I always wondered why I looked the way I did and why my thighs looked different. I would always wonder why I couldn’t have the skinny gene the way my sisters did. That numerical value chased me.”

Ibrahim explains that she began restricting food when she hit puberty around the age of 13. Restriction manifested itself in villainizing food, and thus cutting out bread, pasta, sugar, chocolate, and soda.

“I used to track my calories and would always try to stay in a deficit. My google search was always ‘how to’ because I always wanted to exit this body I was in,” Ibrahim tells Egyptian Streets.

An important element Ibrahim talked about was how sports made her hyper aware of her eating disorder.

“I used to train ballet ever since I was three years old. Because I was bigger than most girls in my ballet class and I looked different from what I should have been, I was told that if I wasn’t going to shed the weight, then I wasn’t going to be allowed to compete. My coach would tell me to run up and down the stairs in my house so I could lose some weight. She would make me sit on the floor for the longest time so I could become flat. Because no ballerina should have fat. Remembering these instances still trigger me until this day,” Ibrahim added.

Ibrahim’s recovery journey was a long and painful process, especially in Egypt, where eating disorders are stigmatized and undermined.

“It does get better. I started going to therapy, which wasn’t very encouraged at the time, more consistently the senior year of my high school. I do know the value of my body now, and that’s not something I say lightly. I am now able to recognize my self destructive behaviors and I know where they stem from. I wouldn’t be able to be where I am if there weren’t people around me who shared similar experiences. Because it is a universal experience, and it isn’t addressed enough where we live,” she explained.

It is important to note that Egypt’s cultural dimension adds more complexities and obstacles when it comes to dealing with eating disorders. Culture plays an important role in the way it advocates and responds to mental health problems.

“We have normalized diet culture in our conversations and daily lives. In the simplest way, Egyptian family gatherings always find a way to open this conversation. It always starts with a simple question of how you’re doing and then it changes to whether you lost or gained weight,” says 22-year old Fayrouz Hefny, a graduate student at the American University in Cairo, also with disordered eating habits.

Hefny reiterates how accepting our bodies in a culture that constantly attacks it is incredibly hard, simply because of the images we uphold in our heads.

“We’re congratulated for weight loss. We never see eating disorders as mental illnesses, it’s not in our culture to think that,” Hefny implies.

The path ahead: moving forward towards recovery

Despite challenges that arise when it comes to destigmatizing eating disorders in Egypt, new services have been emerging to provide support to those struggling. The services include support support groups as well as therapy.

The Good Hope Psychiatry Clinic in Egypt is a driver for change in the path of eating disorder recovery. The clinic offers varying treatment options such as individual psychotherapy, nutrition consultancy, family therapy, and psychiatric meditation if needed. Each patient receives assessments and interventions from the psychiatrist who provides individual psychotherapy and the nutritionist.

“The main problem in treating eating disorders in Egypt is that people often are in denial or have a lack of insight. I have encountered many patients who were fearful of treatment because they thought that meant they were going to gain their weight back,” says Dr. Adly El Sheikh, Psychiatry Consultant at the Good Hope Psychiatry Clinic

According to El Sheikh, the path to recovery first starts with asking the patients if they are happy with their behavior and if they think this behavior has helped heal the shame they have towards their bodies.

“Psychotherapy is the main treatment of eating disorders. The journey of healing is divided into two areas, the first one targets the eating disorder cycle. The eating disorder cycle consists of shame, restrictive patterns, binding, excessive guilt, and in many cases, purging. The first direction in the treatment plan is to break the cycle. The second area in psychotherapy is addressing the underlying problem. The shame that a person has over their body is often a reflection of a deeper insecurity,” says El Sheikh.

Eating disorders fuel a sense of control, reflected in restriction for those who struggle with anorexia, or reflected in purging after a binge. As El Sheikh explains, the sense of control is often a reflection of a lack of control over someone’s life or a compensation of a deeper insecurity.

“We often use medication to help and sometimes need to resort to hospitalization when complications arise, such as cardiac complications. At the Good Hope Psychiatry Clinic, we are a team of eclectic psychotherapists, we use a wide range of therapy treatments such as Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), or Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (DBT). We use our tools according to each person and their needs. Involving the family is essential in some cases bcs it’s hard treating mental health problems without their involvement,” explains El Sheikh.

Comments (6)

[…] The Distorted Perceptions of Living with an Eating Disorder in Egypt The Relationship Risk: The Dating Experience with Strict Parenting […]

[…] https://egyptianstreets.com/2022/03/04/the-distorted-perceptions-of-living-with-an-eating-disorder-i… […]