Known as the pearl of the Egyptian desert, Siwa’s crystal blue waters and golden-hued land have impacted and stimulated the nation’s unique aesthetic culture throughout the years. Egyptian women in Siwa wore colorful traditional costumes. One such example of the latter is the Tidiri colorful dress, which serves as symbols that communicate visually in a silent language.

Fashion, or costume in the past, was akin to visual literacy: each textile carried a story that symbolized culture, class, status, land, religion, or even age. It is similar to reading a piece of text of a community or nation’s history, only it means reading clothing’s symbolism and how it is worn.

One example of this is the “Sunburst” embroidery pattern that is often seen in silk threads in Siwa’s traditional costumes. There are many interpretations as to why this embroidery pattern, in particular, is repeatedly seen in Siwan costumes, one being Siwa’s well documented connection with the ancient Egyptian sun god Amun-Ra. Another interpretation being that it was a reflection of the land they inhabited. Inspired by the colors of their land, women in Siwa often wore the colors red, orange and yellow, which are similarly associated with the sun and the desert.

The clothes we wear tell stories of a nation’s culture and heritage – aspects that can easily be erased if they are not properly documented.

Local ownership of costume heritage

Vibrant, and distinctive, Siwa’s traditional costume has entranced designers over the years, so much so that popular and renowned English singer Adele was once seen wearing a traditional embroidered black wedding dress famous in the Egyptian oasis Siwa. The dress sparked controversy, after Parisian fashion house Chloé announced that Adele’s dress was, in fact, of their own design. Yet, it also triggered a key conversation, for it revealed just how much local ownership of fashion has waned, and has been appropriated by global fashion houses that are appropriating communities’ designs without permission.

Due to modern ideas on fashion, embroidery or pattern is simply seen as a trend, but these patterns also carry sacred meanings, unbeknownst to those who have appropriated them. Many famous motifs found in Siwan embroidery also bear protective powers. Some of the most popular protective motifs include the khamisa and its derivatives, as well as the evil eye.

“Religion, magic and ritual were present in practically every aspect of the life of an Egyptian. Egyptians have always been extremely religious, and so that religious aspect has always been present in their costumes as well,” Yasmine El Dorghamy, founder of Egypt’s Heritage Review, a bilingual publication dedicated to Egyptian history and heritage, tells Egyptian Streets.

Rawi, in Arabic, was a term used for the Egyptian storyteller, and the craftsman who earns a living from retelling the country’s oral history. Without the Rawi’s stories, many of the histories, legends and myths would have been long forgotten.

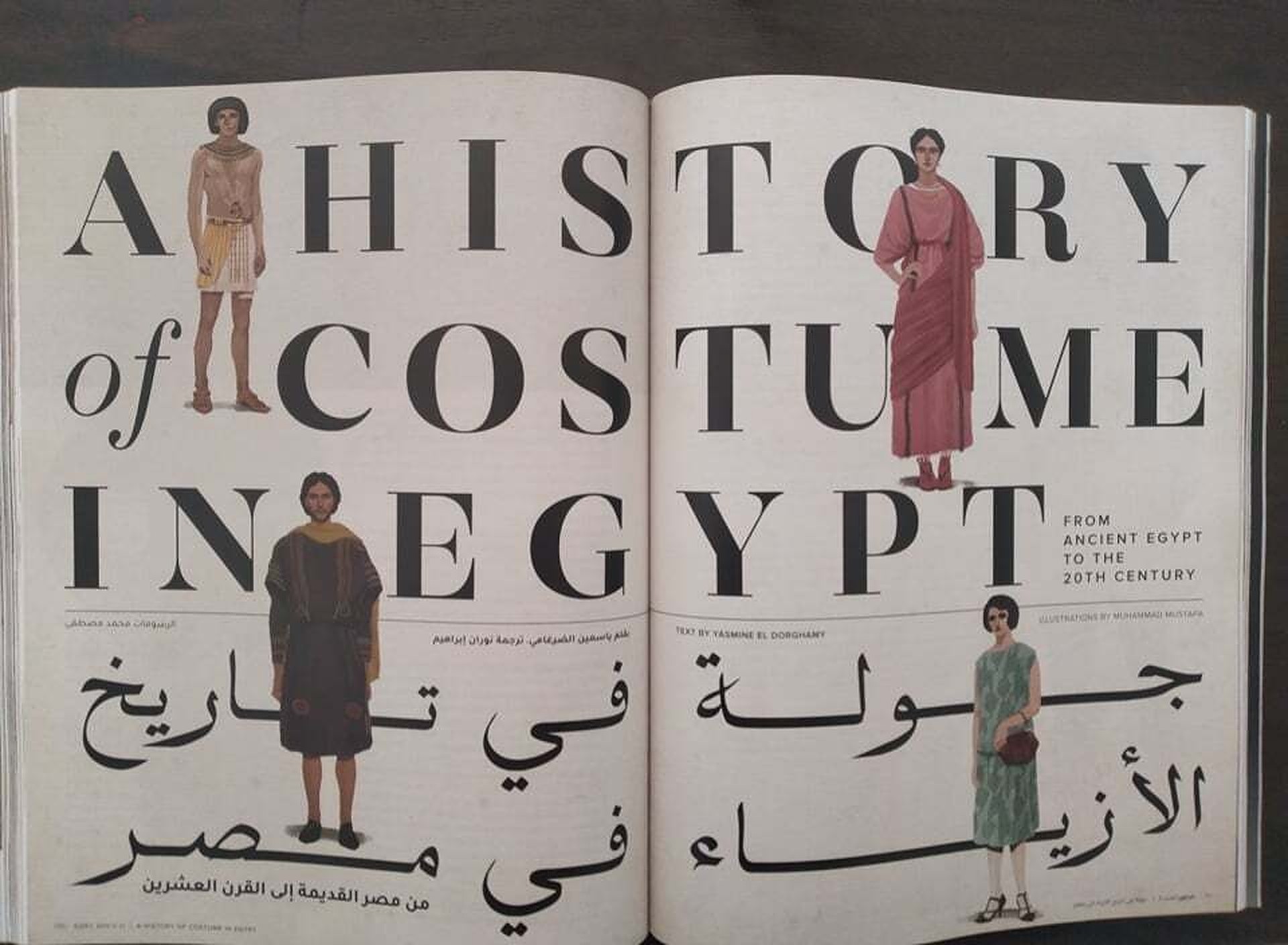

Following its tradition of producing an encyclopedic volume for a selected topic every year, the eleventh issue of Rawi is dedicated to documenting Egypt’s vast fashion heritage, covering a significant gap in the recording of the history of fashion in Egypt.

The 200-paged volume traces the fashion history of Egyptians from the Old Kingdom, the New Kingdom, the Ptolemaic period, the Greco-Roman period, the Byzantine period, the Caliphate of the Fatimids, the Ottoman rule to modern-day Egypt. Yet, what is particularly distinctive about this issue is its attempt to bridge the significant cultural gap that currently exists between the West and the East, and illustrate how modern fashion has lost its memory of ancient dress, particularly its relevance and impact in our world today.

Irrespective of geographic location or ethnic and religion diversity, the review illustrates how the inhabitants of Siwa and the Nile Valle were all heirs to the same legacy, and their costumes provide evidence of the unity of the country and how all of these communities, despite their difference, were all part of a well-integrated and multicultural nation.

Is Fashion Dead? Reviving Memory and Celebration of Clothing

According to Teri Agins in his book, ‘End of Fashion’ (1999), the world is currently experiencing an end to fashion, as today, a designer’s creativity expresses itself through marketing rather than the actual fabrication of the clothes.

Fashion theorist Barbara Vinken, who uses the term ‘post fashion’, underscores that modern-day designers are part of a cyclical revival of forgotten fashions due to the industry’s capitalistic objective to sell more clothes. Fashion critic Vanessa Friedman eloquently describes it as , “designers are effectively running on a creative treadmill that is unsustainable”.

“The world is sadly losing color,” El Dorghamy says. “It’s sadly losing its diversity and variety. Something that has been breaking my heart while working on this edition is reading about the descriptions of travelers who would visit Egypt or Constantinople during the seventh, 16th and 17th centuries, and describing all of the different ethnicities and their interesting clothes and how they could identify all of the different ethnicities through the national costume, which was always distinct and and unique. But today, we’re all dressed the same.”

Moreover, the term ‘fashion’ is also increasingly being challenged, and there is a quiet revolution happening globally against ‘fast fashion’ encapsulated in brands such as Zara and H&M. The celebration of clothes – of fabrics, color and patterns – is slowly being revived. Fashion scholar Jessia Bugg calls into question the preeminence of industry-driven definitions of fashion, as it should encompass the spaces that are beyond the catwalk and the traditional store space, and are more into performance, art galleries and exhibitions.

The return of exhibitions, and of celebrating clothing through the exhibition experience, is according to fashion forecaster Lidewij Edelkort, a testament to a “nostalgia for the heydays of creation and couture.” He refers to the popular Alexander McQueen exhibition, Savage Beauty, as an example of how the world is transitioning towards “culture” and is experiencing the “exodus of fashion.”

As exhibitions reopen around the world, particularly following the COVID-19 initial phase of social distancing which resulted in a halt in production and collaboration, artists are now exploring new ways to engage people with their work. Visitors are pulled into the entire journey of art.

This new experience has also seen revival in Egypt, such as the launch of Egypt’s first gallery dedicated to contemporary and collectible design, Le Lab. The exhibition, titled “Intermission,” displayed Mohasseb’s creative process against the backdrop of a stunning gallery, which offers a variety of settings and routes that allow the audience to walk through different rooms.

Against this context, Rawi Heritage is bringing the celebration of culture and clothing, rather than ‘fashion’, back on its feet.

“We produce this edition to help designers understand how to approach the research and all of the different facets of the history of clothes in Egypt as they work because there is a lot of misinformation online. We hope to set the record straight about a lot of things through Rawi through our experts and specialists who contributed with articles that are based on sound academic research,” she says.

Preserving this heritage starts with protecting the brain of the industry, which is through sharing knowledge, connecting academic experts with artists and designers, and bringing back inspiration as the key cornerstone of modern fashion.

Comment (1)

[…] نهاية الموضة وعودة الثقافة: “الراوي” يحيي ذاكرة ا… […]