Drawn by the gods, revered by the people: the ibis is an elegant window into antiquity. For millennia, this soundless bird has been Egypt’s marker of intelligence and savvy, companionship and patience. Its salience in symbology is undeniable, and today, the ibis continues to be one of Egypt’s most beloved creatures.

Traditionally known as abu minjal (i.e. creature of the sickle), the ibis is a scenic, non-confrontational companion of Egyptian farmers; it lingers in the marshlands, preying on unwanted critters from earthworms and insects to frogs and other invertebrates. Fondly dubbed helper of the land by farmers, modern Egyptians have developed a subtle yet widespread attachment to the animal.

With three central breeds — the African sacred ibis, the glossy ibis, and the northern bald ibis — Egyptians have grown accustomed to seeing variants of the bird along the Nile banks.

This fondness is not new to Egypt.

Rather, fondness for the ibis is inherited.

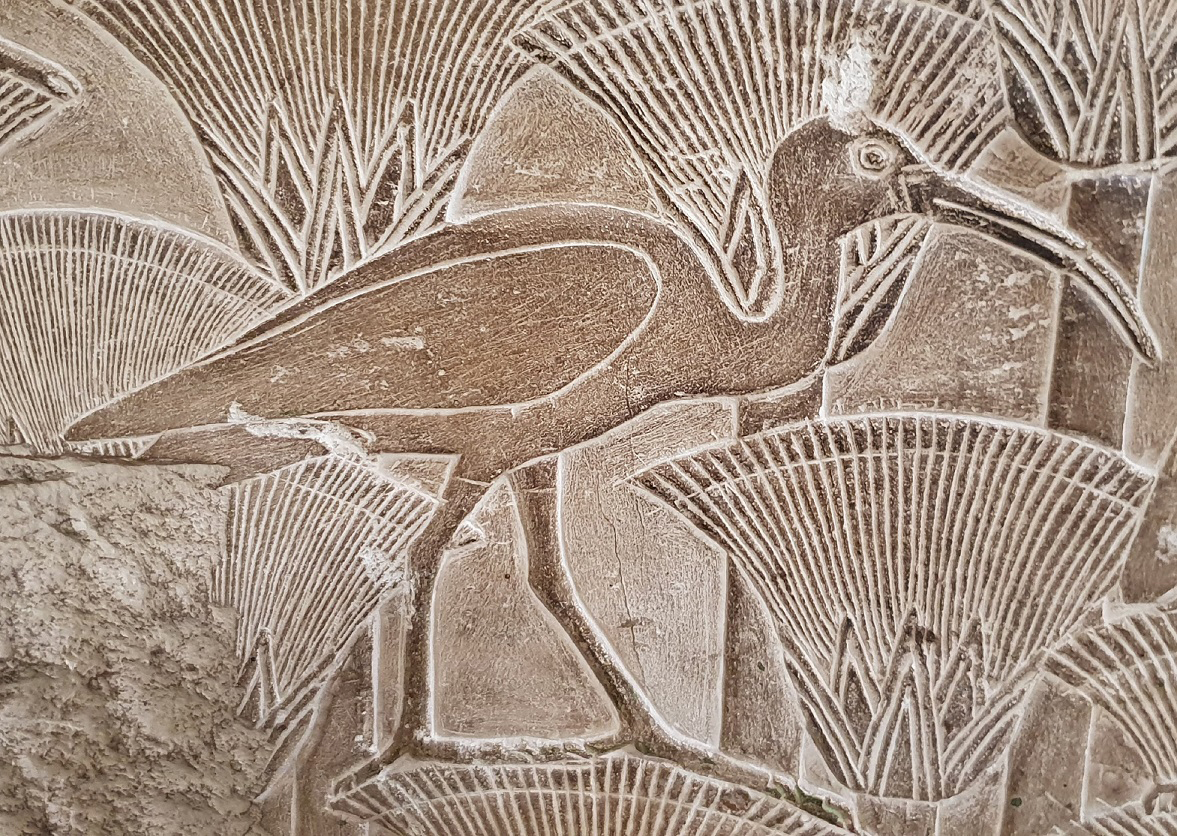

Ancient Egyptians venerated the African ibis in particular, mummified and sacrificed it in the name of Thoth: a recognizable face in the Egyptian pantheon. As the central deity of writing and wisdom, Thoth carries the image of an ibis from the shoulders up – never featured without a long bill and rounded head. His Egyptian name, Djehuty, translates directly to “he who is like the ibis,” a clever and patient creature whose primal, instinctual nature seems muted in comparison to inclinations of the animal kingdom.

Between 650 BC and 250 BC, the ancients honored Thoth with countless votive offerings, sacrificing the bird itself in hopes its tranquil nature would help “cure illness, gift long life, or even sort out romantic troubles.” The ibises were interred in necropolises across Upper Egypt, and although a tragic and “unfortunate honor,” this has helped scholars mirror Egypt’s modern admiration to its ancient one.

Appearing in scenes within the Book of the Dead, the African ibis is also associated with themes of balance, justice, and integrity. Some scholars have even speculated that, as a result of this deep-seated respect for the ibis, ancient Egyptians may have taken to breeding them in captivity, while also keeping them as pets, and allowing them to roam farmlands freely.

Despite this, the African sacred ibis no longer exists in Egypt.

Still, it is a staple of several African nations. Known widely as only the sacred ibis, its taxonomic classification is Threskiornis aethiopicus, appearing in wetlands and along tidal flats. Most commonly, it is found in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Iraq, but is known to migrate closer to equatorial regions during colder months.

The species, interestingly enough, was not prone to breeding in Southern Africa. It was only after the construction of dams and irrigation plants that ibis was introduced to commercial agricultural practices in the latter half of the 20th century.

Its revered status is a commonality between nations, and with the African ibis’ introduction into Europe in the 18th century, fascination continued to grow. Feral colonies now exist in Italy, France, Spain, the Netherlands, Florida, Taiwan, and the United Arab Emirates.

Still, the global fame and local extinction of the African ibis has not changed Egypt’s attachment to the ibis as a species. If there is one commonality to be seen between Egyptians of the past, present, and perhaps an unseen future, it is the tenderness and awe with which they receive the abu minjal – of all breeds.

Comments (2)

[…] © Egyptian Streets […]

[…] “The Nature of Thought.” Neter is an Egyptian term for a natural phenomenon. Thoth is the sacred ibis bird deity also known as Djehuti, Hermes, and Mercury. The sacred ibis bird is related to the moon […]