In the quiet hours of early mornings, or before iftar and sunrise, I find that one of the best ways to spend Ramadan is to swim in the beauty and magic of spiritual poetry. There is no better time in the year where you can enjoy listening to the sounds of every letter and word, and taste the deep religious meanings that they carry.

Over the centuries, poetry has always been at the heart of Arabic language, and was instrumental to helping people express their devotion to God through metaphors and symbols.

This poetic tradition took hybrid forms in different languages and places, such as in Iran, where Muslim poets such as Jalāl al-Dīn Rumi and Shams al-Dīn Hafez gained immense popularity for their soft and romantic styles.

Ramadan is a chance for many believers to delve into the mysteries of existence and go beyond the routines of everyday life. Many have no clue or clear answers as to why life is shaped the way it is, but between the things a person must do in a day, from waking up and going to work, and the riddle of existence, is an ocean of unspoken words that are yet to become spoken through poetry.

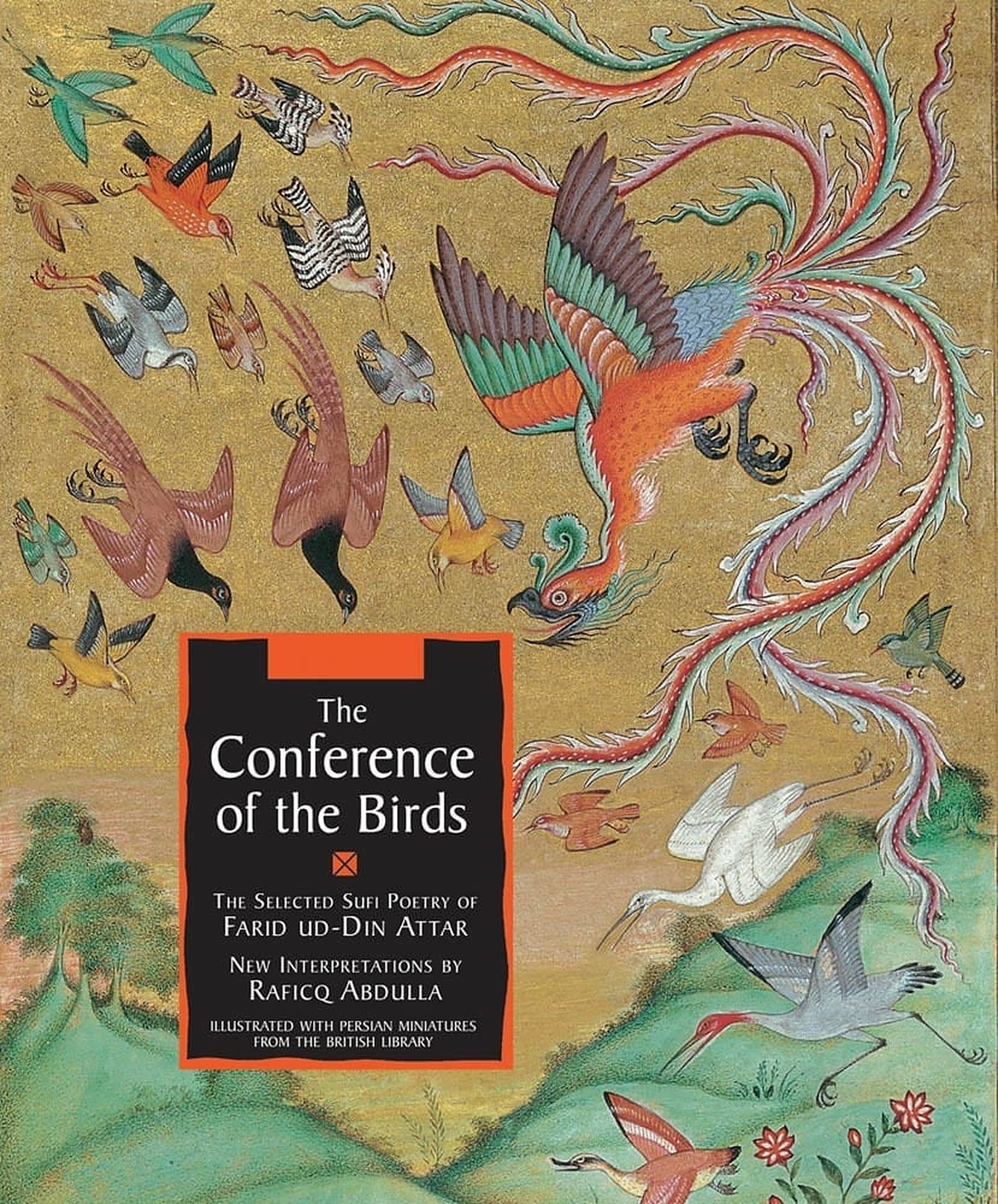

While there are many poems worth sharing, one poem that is unique in its content and imagery is ‘Conference of the Birds or Speech of the Birds’, where Sufi poet Farid ud-Din Attar attempts to capture the mystery of the world in a grain of sand. Composed in the twelfth century, the title is taken directly from the Qur’an, where Sulayman (Solomon) and Dāwūd (David) are said to have been taught the language, or speech, of the birds (manṭiq al-ṭayr).

At the heart of the poem is the core idea that we should go beyond the surfaces and delve into the mysteries of creation. “The secrets of the sun are yours, but you content yourself with motes trapped in beams,” he writes. Looking at the beauty of creation with curious eyes, Attar’s poem shares with his readers the wisdom of escaping the day-to-day routines and embracing the unknown, the concealed, and the bigger picture of existence.

The poem spans over 5000-lines, symbolizing the entire journey of a human to attain enlightenment. In the beginning, the birds come together to decide who is their ‘sovereign’ or their creator. To reach their creator, the bird Hoopoe (King Solomon’s favored bird) calls for all the birds to embark on a journey to meet ‘the Simurgh ’ – the ‘sovereign’ they all seek. But to do so, they must travel to Mount Qaf, which is a mythical mountain wrapped around the world.

Each bird represents a human flaw that prevents them from attaining ‘enlightenment’, such as unhealthy forms of attachment, greed, or pride. The Nightingale fails to complete the journey due to the attachment it shares with the rose, the Parrot fears death and prefers to stay in the comfort of being alive, and the Hawk is too proud of his social-status to seek another sovereign.

The trails of the seven valleys of the mountain build on one another, showing how each stage in life is not a random coincidence, but helps one move to the next higher phase. Before the birds reach the valley of love, they first have to endure the trials of the valley of reason, only to become more mature and independent and learn that love is different from reason. After reaching the valley of understanding, which teaches that knowledge is temporary, the birds reach the valley of independence and detachment, where they learn to renounce inner and outer attachments.

In the final valley, which is the valley of unity, the birds recognize unity is achieved when the self ceases to exist, and instead turns into a drop in a vast great ocean. They come to realize that they are only part of a larger grand design, and that their self is only but a shadow, or a barrier, to reaching the divine. “The shadow and its maker are one and the same, so get over surfaces and delve into mysteries,” he writes.

Sufism, as a religious philosophy, primarily aims at the expansion of the soul to realize the unity and oneness of all creation. Rather than focusing purely on the self, and the desires of the self, it is about looking outwards and realizing one’s purpose that serves the entire creation.

From this poem, Attar illustrates the core of Sufism: God doesn’t exist in the form of some external substance or separately from the universe, but is reflected in everything that exists.

The poem is essential to a deeply-rooted belief in Islam overall: whichever path we seek, and wherever we are, God can be found within us and within the creation that surrounds us. Rather than have to constantly strive to connect with God as a being that exists outside of us, God’s presence can be felt in the stars, the skies, the ocean, the trees, and the wind – all of which carry the same spirit.

Any opinions and viewpoints expressed in this article are exclusively those of the author. To submit an opinion article, please email [email protected].

Comments (2)

[…] […]

[…] […]