Salt levels the upper lip, and a pale Alexandrian sky sits over Fouad Street. A statue of Alexander the Great, straddled on a black horse, points down its avenue, and the Mediterranean cups its end. From the Ptolemies to the Pashas, Fouad Street has witnessed Alexandria’s momentous past, been home to its gracious intellects, and remains one of its prized locations.

Considered one of the oldest established roads in the world, it is the central artery of coastal Alexandria. It was designed to carry the weight of trade and commerce, as the main passage of movement and activity within the city. Given its nature as the core node of Alexandrian infrastructure, the street had two main gates at its inception: the Sun Gate (Eastern) and the Moon Gate (Western).

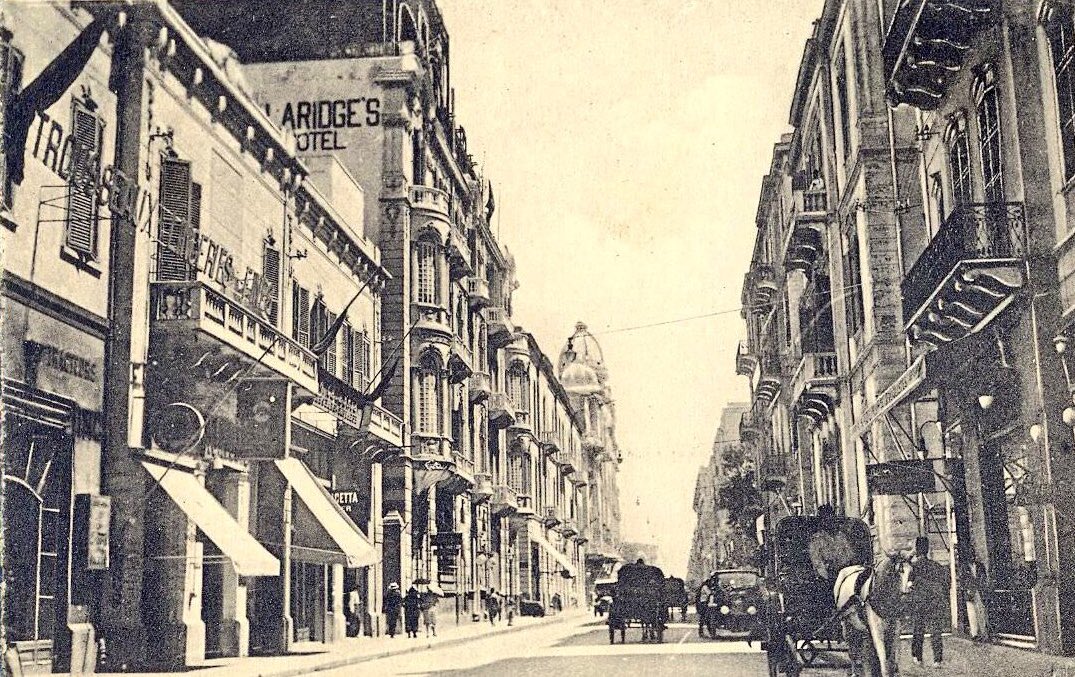

Brought to life centuries ago, Fouad Street stood the test of time and is now considered a melting pot of oddly-arranged persuasions. From its commission under the keen eye of Greek architect Dimokratis in 400 AD, the road was already kaleidoscopic when it came to foreign fusions. Roman-Italian architecture punctuates its corner lanes, while Grecian and French influences sway its decorative nature.

The street would later be part of Alexandria’s Latin quarter, which saw additional, uniquely designed structures rise in the 19th century by Italian architect Phillip Beni in 1880; this was at the behest of Khedive Ismail, of the Muhammed Ali bloodline.

Though over time, as Egypt was in the throes of historical and cultural transformations, the road was known by names other than Fouad. Rather, it saw an evolution of titles, some of which came to define it: the King’s Road, Bab Rashid (Doorway to Rosetta), and as a result of Pan-Arabist influence, al-Horreya (Freedom), and Abdel Nasser.

It earned the name Bab Rashid, given it was the only link between the city of Rosetta and Alexandria in the 19th century. Though the title would not stick for long; in 1920, the street would inherit the name of its king, King Fouad I, and remain known as such despite later attempts at changing it by coup d’etat figurehead Gamal Abdel Nasser.

As such, both 1952 revolution-inspired names, al-Horreya and the more controversial Abdel Nasser Street, were forgotten in time and relegated to textbooks.

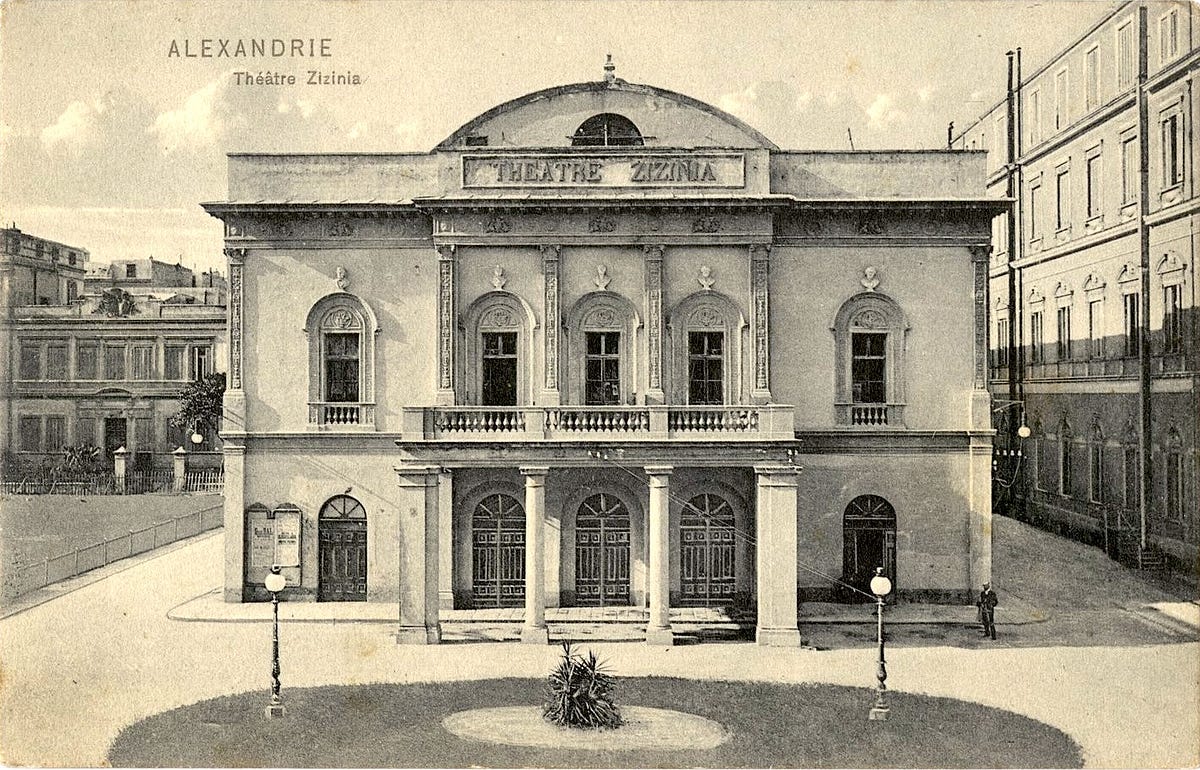

To this day, the aristocracy of the past remains intact, and much of Alexandria’s influences have blossomed outward from this singular road. While some landmarks still remain, others can be found in time-worn illustrations – such as the Muhammed Ali Pasha Club (now Alexandria Art Centre), the Zizinia Theatre, and the Khedive’s Hotel.

Unfortunately, while the road itself remains, many of the villas and age-old architecture did not make it to the present. Still, Fouad Street was a function of more than just its architecture; it was home to some of Alexandria’s most prolific writers and scholars.

Author of The Alexandria Quartet (1962), Laurence Durell, penned his works under the shade of its history, and Greek poet-scholar Constantine Cavafy worked similarly with his verse. Cavafy was the “first [Alexandria-based] scholar to have his works published in international journals,” and his house on Fouad Street was later turned into a museum in 1992.

Having endured for centuries, Fouad Street has witnessed Egypt evolve—harboured its kings, homed its poets, and honed its architectural beauty. It is important that efforts to preserve this location continue to increase over time. While the modernisation of Fouad Street is not out of the question, a protective appreciation would help preserve the structures that already mart its present.

Comment (1)

[…] origins dating back to 331 BC when it was known as Via Canopica, Fouad Street is the world’s oldest planned street that’s still inhabited today. This remarkable […]