Renowned Egyptian journalist, Mohamed Hassenein Heikal once stated, ‘modern Egyptians can feel ancient Egypt better than any Western archaeologist’, a sentiment I wouldn’t question.

Egyptians have a natural emotional connection to their ancient past lived and breathed not only through their physical surroundings, but their language, food, customs and traditions. The connection to ancient Egypt is even present when a newborn listens to the most famous Egyptian lullaby to help them sleep – Nenna Ho.

Even though I have visited Egypt more than 20 times, studied Egyptology at doctorate level, spent years trying to learn aamaya and Fus’ha, and worked in museums for my entire adult life, I am still innately aware of my own shortcomings as a curator and Egyptologist of Anglo-heritage. I will always have certain blind spots.

No matter how many visits I make to Egypt, I will never be able to replicate what it is like to grow up in Egypt, to understand class structure, family relationships, and the ever more complex social, political and religious fabric of day-to-day life. But I am in a position where I can work together with Egyptian communities to help amplify their voices, share different narratives and promote the museum as a place for two-way knowledge exchange and engagement.

When I took up the post of Senior Curator of the Nicholson Collection of Antiquities at the Chau Chak Wing Museum, University of Sydney earlier this year – returning to my home country four years after working as a Postdoctoral Researcher in Egyptian Antiquities at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge – I set foot inside a brand-new museum with shiny new showcases and displays.

You see, the Chau Chak Wing Museum had only opened less than 18 months earlier. This also meant it was the first time Egypt had been given such a large, permanent footprint occupying two gallery spaces – the first titled ‘The Mummy Room’, dedicated to the Museum’s collections of Egyptian coffins and human remains, and the second titled ‘Pharaonic Obsessions: Ancient Egypt, an Australian Story’, exploring the way Egypt has found its way to Australia through the obsessions of collecting and fieldwork.

However, like so many displays of Egyptian antiquities worldwide, its approach to Egypt’s past is primarily through the Western gaze.

While much has been written and debated about the circumstances in which Egyptian antiquities have left Egypt , and if cultural property should be returned, these debates typically result in gridlock.

To try and counteract this, or perhaps more to the point, find practical and inclusive ways forward, there has been some attempt in recent years to work more closely with Egyptian source communities in the interpretation and display of their dispersed cultural heritage, and to move away from mono-Western narratives of Egypt’s past.

There have also been efforts to openly recognise and acknowledge Egyptian Egyptology and Egyptian heritage, as well as past injustices – subjects that have historically been silenced and sidelined.

Although we have a long way to go, there are a number of museums, exhibitions and cultural heritage projects which have been actively trying to make a difference. For example, Egypt’s Dispersed Heritage project, the Place and the People project, the Fitzwilliam Egyptian coffins project and ‘Pop-Up’ Museum, the ‘Photographing Tutankhamun’ exhibition and accompanying publication and the recent re-display of the ancient Egyptian galleries at the National Museums Scotland.

Egyptian Collections at the Chau Chak Wing Museum

The Nicholson Collection at the Chau Chak Wing Museum, University of Sydney holds the largest number of Egyptian antiquities not only in Australia, but the Southern Hemisphere.

The collection was formed in 1860 by British antiquarian, medical doctor, statesman and philanthropist, Sir Charles Nicholson, whose aim was to procure an international teaching collection for the University spanning a wide range of periods and material types.

In 1856-1857, Nicholson set off on a grand voyage to Egypt in the pursuit of collecting Egyptian antiquities (he also went onto Europe and returned to Egypt once more in 1865), amassing more than 400 Egyptian artefacts, including coffins and mummified human and animal remains, statuary, stelae, and stone and ceramic vessels.

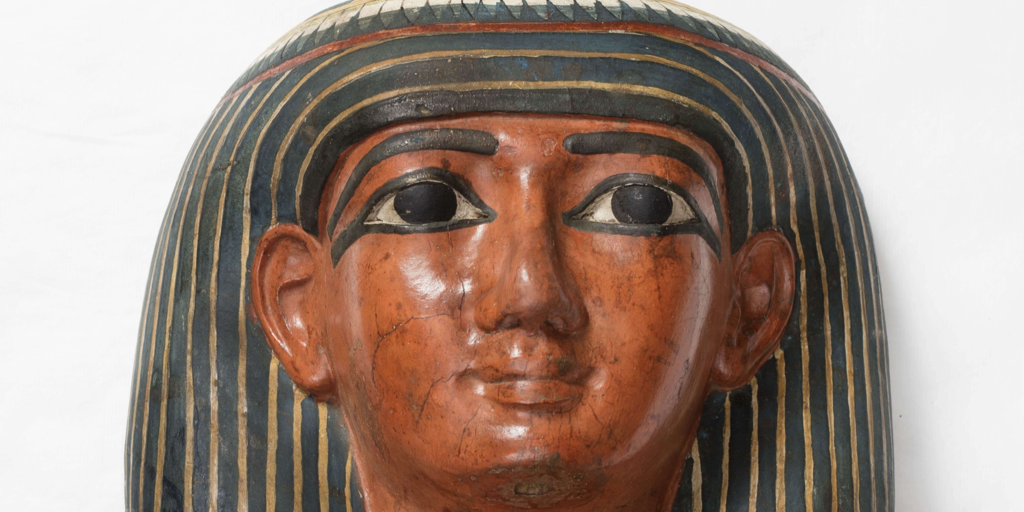

Among the highlight objects, includes the Third Intermediate Period (c. 1020 – 945 BC) inner coffin and mummy board of Meruah, the late Third Intermediate Period (c. 725 – 700 BC) inner coffin of Padiashakhet, the Late Period (c. 664 – 525 BC) coffin of Mer-Neith-It-Es , the Roman period (c. 100 AD) child mummy of Horus, and the granodiorite bust of Tutankhamun’s general, Horemheb, before he became king.

While Nicholson established the foundation of the Egyptian antiquities collection, it grew exponentially in subsequent years through the Egypt Exploration Fund – in return for their financial contributions, the University was sent crates of nearly 1000 artefacts from excavations which took place between 1888 and 1963 –, private donors (including tourists and migrants), as well as Australian Defence Force personnel who were stationed or embarked/disembarked in Egypt during World Wars I and II.

While the museum holds the oldest and largest collection of Egyptian antiquities in Australia, we are one of many Egyptian collections scattered throughout the country.

As listed on the website of the Comité international pour l’Égyptologie (CIPEG), Egyptian antiquities can also be found at the Macquarie University History Museum, the Australian Museum, the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences, the National Gallery of Victoria, the Ian Potter Museum of Art, the Museum of Mediterranean Antiquities, the Museum of Old and New Art (MONA), the South Australian Museum, the Queensland Museum, R. D. Milns Museum and the Western Australian Museum.

Then there are, of course, countless other Egyptian antiquities scattered throughout undocumented private collections.

Australia’s First Nations and their dispersed material culture

In a similar way to Egypt, much of the cultural property of the First Nations people of Australia has also become separated from its source communities.

For a period spanning almost 150 years, colonists, explorers, and ethnologists, ‘collected’ ancestral remains and secret sacred objects for ‘scientific’ research, thus becoming dispersed across many different museums, universities and private collections in Australia and overseas.

Australian cultural institutions were also partly responsible for this dispersal as they similarly engaged in international exchange with some of the great overseas collections – exchanging Australian First Nations artefacts in return for antiquities and works of art. First Nations cultures of Australia are deeply rooted in oral histories – reaching back as far as 65,000 years (making them among the oldest living cultures in the world).

Today, as colonisation continues to disrupt the transmission of knowledge and traditional practices, surviving tangible cultural heritage is incredibly important.

As with a number of prominent international collections and individuals helping to reclaim ownership and a voice to Egyptians over their dispersed cultural heritage, Australia has also only relatively recently (i.e. within the last three decades) started to publicly and openly recognise past wrongdoings and support First Nations self-determination.

Most cultural institutions in Australia, for example, now include dedicated roles for Australian First Nations professionals.

At the Chau Chak Wing Museum, we have a Curator of Indigenous Heritage (Marika Duczynski), an Indigenous Advisory Committee, and for the University of Sydney there is an overarching Indigenous Research Strategy overseen by the Deputy Vice Chancellor, Indigenous Strategy and Services (Professor Lisa Jackson-Pulver), Repatriation Committee for the care and return of ancestral remains of First Nations peoples and a school of Indigenous Studies and Aboriginal Education.

We also seek to incorporate the many languages of Australian First Nations peoples through multilingual label text and we actively work with First Nations communities across the country to be a safe space for learning, healing, exchanging ideas and celebrating the continuing cultural heritage of Australia’s First Peoples.

It is within this context that I feel strongly about taking a similar approach to working with Egyptian source communities regarding their dispersed cultural heritage in Australia.

In order for the Museum to fulfil its responsibilities to Egypt and its people, we need to involve contemporary Egyptian communities in long term, meaningful ways.

Thus, in collaboration with local and international colleagues in Australia, the UK and Egypt, we have embarked on an in-depth project to understand how ‘Western’ museum exhibitions and displays of Egyptian collections need to better engage modern Egyptian voices and perspectives, be more inclusive and open to two way dialogue with Egyptian communities. We also aim to connect second and third generation Egyptians more deeply with their cultural heritage and make our collections more relevant to audiences, particularly non-traditional museum going audiences in culturally underprivileged areas.

We are aware that many museums before us have been doing community consultation work, but what we seek to do differently is open ourselves up to criticism; engage directly with community feedback and place this feedback at the forefront of what we do.

Using the Nicholson Collection at the Chau Chak Wing Museum as a case study, we are collaborating with the British Arts and Humanities Research council funded Egypt’s Dispersed Heritage Project, led by Dr Heba Abd el Gawad and Associate Professor Alice Stevenson based at University College of London, Institute of Archaeology, to conduct a series of intense focus group discussions with members of the Egyptian-Australian community. These will be taking place in Sydney on 10 and 11 September 2022.

We also want readers to educate us. What do you think museums can do differently for Egyptian communities?

This is the first part of a monthly public conversation series published on Egyptian Streets.Co-written by Melanie Pitkin, community participants and other internal and external collaborators. This project aims to explore and engage on a diverse range of topics guided by the needs and expectations of the Egyptians around the world, which we hope will help to inform a new mode of museum practice, engagement and display internationally.

To find out more about the Chau Chak Wing Museum’s Egyptian community engagement work, please contact: [email protected].

The author would like to thank Dr Heba Abd el-Gawad, A/Prof Alice Stevenson, Candace Richards, Marika Ducynszki, Sara Hany Abed and Faten Kamel for their thoughtful comments and feedback in helping to shape this article.

Comments (6)

[…] https://egyptianstreets.com/2022/09/02/egyptian-collections-in-australia-a-curators-perspective/ […]

[…] working in museums in Australia and the UK, and providing support to colleagues at museums in Egypt.[…] annual inflation rate surged to 14.9 percent in April,…© 2019 Egyptian Streets. All Rights Reserved.Subscribe to the fastest growing newsletter in […]