The deep sound of the aulos, a double-reed flute, echoes across the Roman amphitheater, where a crowd of Egyptians and Romans, clad in the best linen and togas, admiringly sit in silence. Upon the end of the last note, a wave of deafening applause ensues. Alexandria’s ancient citizens make way to their homes, mere streets away, while some playfully make way to late-night taverns.

In many history books, there are descriptions of architecture and key monuments, but the human experience of the people that lived in these households and structures during that period is not studied enough; this also applies to how architecture can affect the way humans communicate, live, and interact

Though there isn’t much archaeological evidence to form a full and clear picture of how Egyptians lived during Graeco-Roman periods, papyri (ancient writings) from urban and rural sites along with a few archaeological remains of houses, buildings, and schools have helped researchers to go beyond the focus of tombs and temples of royal ancestors, but also how ordinary populations lived.

One way to explore the relationship between the Egyptians and the Romans is by looking at housing.

Just as Egyptians placed great care and attention in building tombs where mummies were placed for the afterlife, they also took into account the intricate details of building a house.

The Egyptian home: a temporary resting place

Housing in Egypt has had origins even before the country was unified. What merely started as modest homes of mudbrick evolved in time and structure.

Contrary to popular belief the house is more than just a place for rest; it is also a place where people can express ownership over their land. It is where they can curate an identity that is unique to their own social backgrounds, and in times of political conquest, it is a space that distinguishes them from the conquerors.

Though urban planning was not completely absent in ancient Egypt before the Greco-Roman period, there is debate among scholars as to whether it was top-based or community-based. According to one scholar, the Egyptian house before the Graeco-Roman periods was characterized by a laissez-faire approach with regard to domestic space, which was largely based on consensual negotiations among the Egyptians themselves, rather than a top-down process of agreements.

Living quarters, particularly in the rural areas, seemed to be mostly left to local social negotiation, and the only houses that were imposed and officially planned were the villages of workmen, who were responsible for building monumental architecture such as religious temples, administrative buildings or royal tombs.

Beyond this, Egyptians had to contend with not only building their homes, but also creating the bakeries, religious shrines, breweries, and workshops that were so crucial to their survival.

Urban houses: Social class and status

The idea of the typical ‘Egyptian’ house has changed after the conquest of Egypt by Alexander the Great. While Egyptians carried their own style in the architecture of houses, these houses were also affected by cultural and historical shifts.

For instance, the classical architectural styles appearing in Alexandrian monuments, which are characterized by the shape of the colossal, floral forms and monumental screen walls, often give the false impression that the Greeks and Romans entirely dominated the city, and always had a Greek appearance.Yet recent research shows that the Greek and Roman styles in architecture were infused with local Egyptian iconography that was unique to Alexandria.

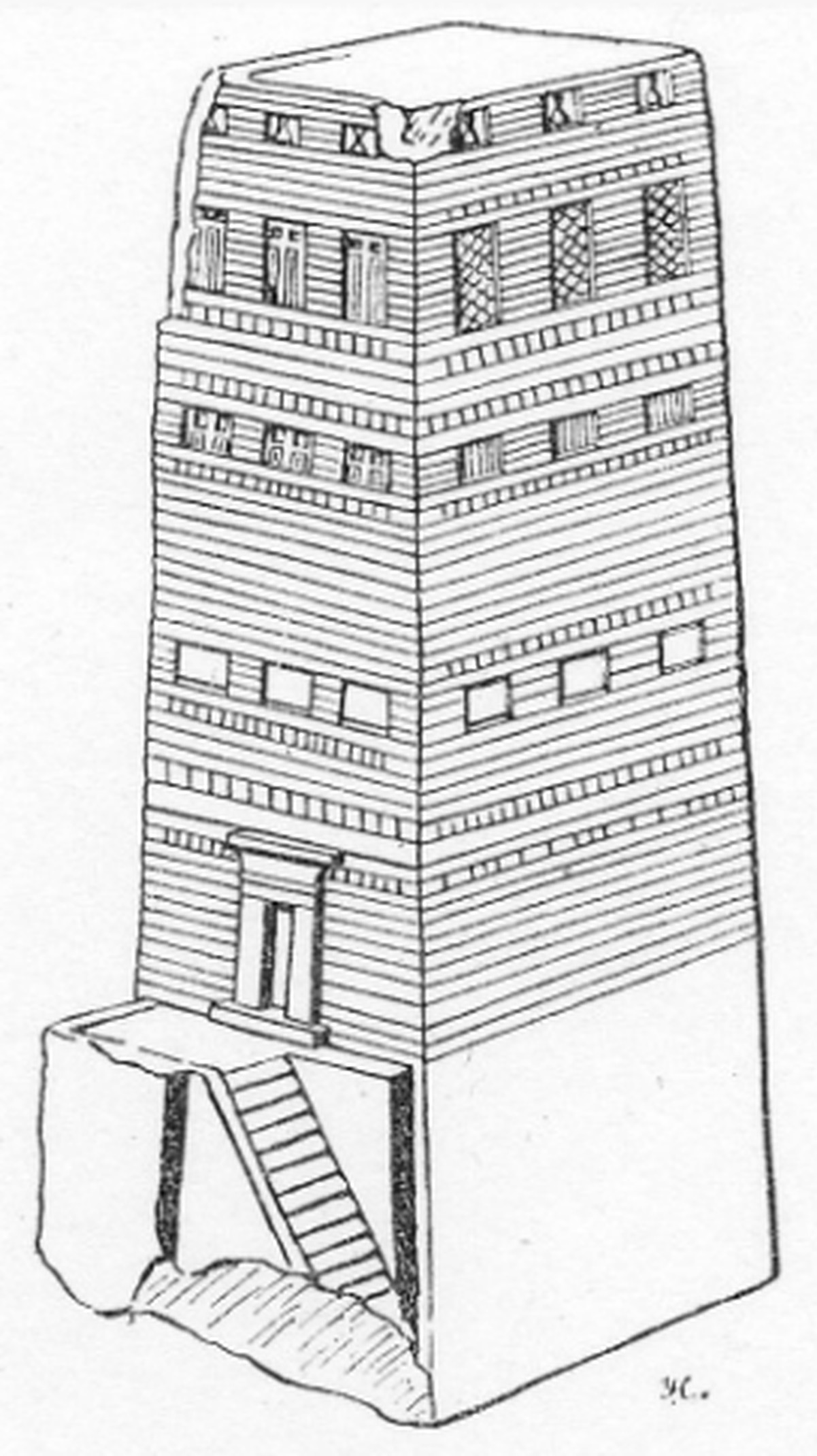

The aithrion-house is one of the first houses found in the papyrus dating back to the second century, which depict a house with a single entrance door, three courtyards, an entrance hall, a flight of steps that lead to the upper stories, and a tower-like gateway that heads towards a central courtyard that is open to the sky.

The two-towered or multi-storied house is another structure, which is a tradition preserved from the ancient Egyptian period, proving the persistence of traditional structures.

According to Alston, the two-towered houses were used to boast the status of the inhabitants and create a clear distinction between the private and the public. During the ancient Egyptian period, wealthy Egyptians usually inscribed their names and titles on the main doorway of their houses. Later on, this was carried on to the Roman period, as visible towers served to identify the names of neighbours.

To live as an Egyptian in an urban area meant that, to a certain degree, there was more privacy, wealth and status, and the traditions of this class in the ancient Egyptian period were also passed down to the Greco-Roman periods. Social interaction, in this case, was limited to the communities that were living in these homes and urban neighborhoods.

Rural houses: The case of Karanis

While urban houses were characterized by social status and the distinction between private and public, the rural areas were a whole other story.

Fusing Egyptian with Greek and Roman influences, the architecture of Karanis – one of the largest Graeco-Roman cities in the Fayoum oasis – is one example where there was an overlap between two systems: top-down organization as well as more localized interpersonal negotiations.

Inspired by ancient Egyptian heritage, Bethany Lynn Simpson, art history professor at Virginia Commonwealth University in Qatar, notes that Karanis was designed to develop several degrees of communal interaction, as private property owners often maintained good relationships with their neighbors through local pathways and shortcuts that facilitated movement and provided alternative routes to the public street system.

Some features in the Graeco-Roman household structure were also used differently in Egypt compared to Greece, such as the tower, gate, and courtyard. A tower in ancient Greece was a rounded tower that served for either storage or defensive structures, but the tower in the documents of Graeco-Roman Egypt was used for different purposes and had multiple storeys, and even existed inside households.

The Egyptian house was characterized by its organic ties to the environment and people. A view of the lush greenery and gardens was seen through the tower house, which was the most common house type for all Karanis properties.

To keep communities and families connected, there was an exterior courtyard space and upper storeys that expanded over time if there was ever a need to house more family members. Courtyards and open spaces were also present to create room for social activity, and the central stairway structure was the only single point of access to upper and lower stories, serving as the main point of connectivity for each room on these levels.

This house design, according to Simpson, implies that the population was not closed off from their neighbors or people living inside the house and that there were many opportunities for close interaction as there was a common passageway that everyone used. Houses were also frequently accessed by people not part of the household group, such as extended family, friends, visitors, and guests.

Ownership rights

Nevertheless, while these household structures suggest that there was a degree of autonomy and diversity, there was an underlying tension.

Egyptians’ right to their land and water rights was threatened, as the creation of the Roman province of Egypt was followed by a reorganization of the system of land tenure.

In some areas in Egypt, around one-third of agricultural land was identified as royal land, and the king also had residual rights over the rest of the land.

There were several private tenancy contracts that have survived from Graeco-Roman Egypt, and there were petitions of complaint by Egyptian farmers who were displaced in favour of someone else who could pay higher rent. In a petition, one farmer complains about being prevented from using the village’s water irrigator “which has been at our disposal since our ancestor’s time” and that the farmers felt oppressed in their villages.

The right for local populations to have ownership over their homes and lands is the starting point for understanding social structures that live on for decades. The Graeco-Roman period can provide a glimpse of the degree of autonomy and control Egyptians had over their public space, and how traditions of competing forces between planned and unplanned public spaces continue to exist to this day.

Comments (0)