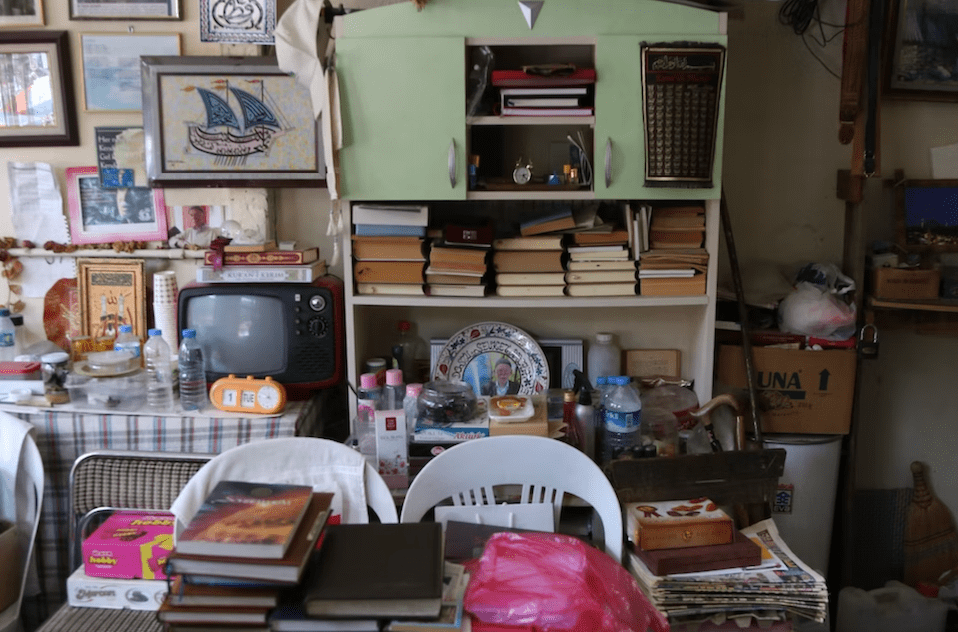

From small porcelain trinkets to closets bursting with winter clothes: Egyptians have, over the decades, developed a proclivity for hoarding karakeeb: unused, miscellaneous clutter that serves a minor purpose, be it sentimental, practical, or simply as comforting good-to-haves. Originating from the word karkaba and karkeb, which means ‘to clutter’, the word has become a go-to to describe this specific facet of Egyptian culture.

Some collections are benign—a grandmother preserving memories of her past, a man whose soft sentimentality prevents him from tossing out his father’s old suit, and a teenager whose developed ties to the aging dollhouse she keeps in the corner of her room.

But not all cases are quite as romantic.

Some Egyptians hoard because of perceived crisis; between history and poverty, being stripped of one’s basic needs seems to loom over households that’ve gone through struggle. Karakeeb to some, it seems, a necessity to others—frozen food, plastic bags, old clothes: they are all things that, in practice, could alleviate foreseeable scarcity.

Egyptian Streets sought to explore all the reasons behind people’s karakeeb, behind the wide-reaching and enduring nature of this phenomenon. Though commonly seen in older generations, almost all age groups in Egypt have their clutter, and participate to some degree to this hunger for hoarding.

After a 24-hour Instagram survey on the Egyptian Streets page, 160 (73.7 percent) out of 217 people answered yes to the baseline question of “does your family/you hoard karakeeb?”

Here’s why.

‘Because I Can’

“My grandma’s house has cabinets of photo albums,” shares Meri (@dietc0ke_princess) on Instagram. “[She hoards] all our stuff since we were babies.”

Not uncommon in the Egyptian household, and many around the world for that matter, is sentimental hoarding: the desire to keep close little things from a bygone era. According to the NHS, many individuals who hoard associate certain items with “strong emotions,” and any attempts to “discard things often […] can feel overwhelming.”

The collecting of memories and sentiments, for the sole purpose of being able to touch the past is a common reason for why Egyptians keep karakeeb. Nadeen (@nadeen_the_discreet) jokes that her family is prone to keeping “weird looking plates and cups,” presumably aged china or miscellaneous finds, “that we’re not even allowed to use.”

“My grandmother is great at it,” laughs Mohamed Sarwat, who sat down with Egyptian Streets upon taking interest in the topic. “Old knick-knacks from Akher el ‘Anqoud, the stuff you would expect grandmothers to keep. My mother is also [in the habit] of keeping plastic bags and old cutlery, for some reason.”

Khadiga Konsouh (@kkdiga) corroborates this experience. “[My family keeps] anything kitchen related mostly, [like] china pieces.”

Though the concept of ‘I keep because I can’ is not only tied to Egyptian romanticisation of the past. Often, it is simply a part of household culture. Egyptian Street’s own Amina Zaineldine (@azaineldine) adds that her father “hoards everything” while her mother “throws everything away,” which begs the question of how different backgrounds could play a potential role in whether or not individuals choose to keep or discard karakeeb. Oftentimes, those who have grown up in a cluttered home are more likely to start collecting things that are of “little or no monetary value, and may be what most people would consider rubbish.”

Both Nadeen and Lina (@lanloonaa) shared that their families are prone to storing old newspapers, without a particular aim in mind.

In a similar vein Azul (@azulmeansbluee_) keeps books, because he can: “do I need a reason?”

The simple answer is no. Karakeeb can be causeless, or full of purpose. Best put by Pat (@s.pat.ula): “[My family] hoards everything because we are proud Egyptians.”

‘Because I Have To’

It is pertinent to draw a line, here in particular, about the differences between ‘collecting’ and ‘hoarding’ as separate tendencies. While the need to keep things because one can often falls into the category of collecting—where items are easily accessible, and often organized such as books and photo albums—hoarding is a more chaotic behavior that manifests itself as true, disorganized clutter.

Karakeeb are a combination of the two, and are often hard to differentiate locally. Egypt has long since struggled with defining the parameters of mental health guidance, and hoarding flies under the radar as a result. Similarly to how depression can be written off as sadness, hoarding is often written off as karakeeb-keeping: undefined.

Most common in those who have experienced poverty, or any capacity of lack, hoarding becomes part of an individual’s lifestyle. From obsolete items, to things that have far outlived their lifecycle, hoarding manifests largely as the keeping of newspapers, books, clothes, containers (i.e. plastic bags, boxes, jars, etc.), and household supplies.

Grandmother Hala Mahmoud insists that her choice to purchase food in bulk is a result of “never knowing what comes next.” She describes the 1950s and 1960s in rigorous detail, wherein under late President Gamal Abdel Nasser importing was banned and a redistribution of wealth left socioeconomic classes in flux.

“My family lost everything,” she disclosed to Egyptian Streets. “We could barely afford things that were a given. I’m not talking about luxuries, either.”

Sevilla (@_route888) argues similarly. When asked about why Egyptians hoard, their answer was simple: “poverty and fear of lack.”

While Mahmoud hoards food, and little containers she insists on reusing, others hoard clothing. Adel Hany (@adel_.hany) notes that his family is prone to keeping heaps of winter clothes. Though Hany does not specify why, between soaring prices and newfound blistering winters due to climate oscillation, one can only assume it is out of some sense of necessity.

‘Because I Should’

Between those who must and those who simply can, are a minority: those who keep because of arbitrary obligation. Be it ethical or practical, many Egyptians’ karakeeb come in the form of “old stuff that [they] feel bad throwing away,” argues Egyptian Streets writer Marina Makary (@marinamakary94). “[Things] we may use in the future.”

These individuals often feel a moral obligation to store away items, in hopes of repurposing them in the future—not because they must, but rather because they should; it is an argument of waste management rather than necessity.

Much like Makary, Mirale Tadrous (@mirale_tadrous) shares that her family is prone to keeping “plastic bags, empty jars, newspapers, [and] anything that can be repurposed.”

Sarwart’s final sentiments ring similarly. “Egyptians love having things on hand—we can’t live min gheir karkaba (without clutter). We might not use it, but we could, you know? That’s it.”

Comments (0)