In 1997, a legislative proposal of drafting laws for organ transplant in Egypt stirred nationwide controversy. 15 years later, on 26 September 2022, Egypt’s President Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi announced the country’s plans to open the Middle East and North Africa’s largest organ transplant center – ushering in a new era for organ transplantation in the country

Egypt now has 37 organ transplant centers, plans to construct the MENA region’s largest transplant facility, and is considering revealing organ donors in the national ID.

While the residue of religious debates still exists within the dialogues of organ transplants, it now exists far less than it did in 1997. Egypt’s long path to normalizing organ transplants appears to be reaching its destination.

Over two decades ago, Mohamed Al-Sharawi, Egypt’s most popular Islamic cleric at the time, publicly rejected the concept of organ transplantations on his weekly television program – declaring that the medical procedure violates God’s creations.

Al-Sharawi’s claims, and his cultural influence on the topic, went against Al-Azhar’s endorsement of the matter around the same time as Al-Sharawi’s speech.

Al-Azhar, the government’s official Islamic advisory body at the time, faced severe backlash for their stance, as some religiously more conservative Egyptians accused the institution of allowing politics to shape doctrine rather than the other way around.

Egypt’s Dar Al-Ifta, the country’s current official Islamic advisory body, also affirmed that organ donations are religiously permissible in a social media press release on 25 September.

Despite attempts to form a regulated and legal process, organ transplants still lack comprehensive reforms during the Mubarak regime. Only kidney transplants were recognized at the time and required approval from the Ministry of Health.

A 2010 law banning organ sales sparked the first sign of hope in regulating organ transplants, but was short-lived due to the disruption caused by the 2011 Revolution.

Twelve years, three presidencies, and two constitutional referendums later, Egypt is reviving the efforts that started in 2010. However, religious discourse existing in debates decades ago still lingers, particularly in today’s public spheres of social media.

Actress Elham Shahin took to social media to share her plans to donate her organs upon her death. Buried beneath the algorithmically prioritized verified comments, social media users criticized the actress for her public announcement.

“You do not own your organs to give them away. It belongs to our Creator [God],” reads one comment, mirroring Al-Sharawi’s speech in 1997.

Amr Adeeb, an Egyptian media personality, took to his talk show, Al-Hekaya (The Story), to express his exasperation over the religious debates arising from the news of Egypt’s planned transplant center.

“I can’t believe we are debating whether this is sinful or permitted while other large Islamic countries have legalized the matter years ago,” stated Adeeb.

Regionally, Egypt lags behind the likes of Saudi Arabia, Oman, Qatar, Bahrain, and Kuwait, who established transplant centers decades ago. The United Arab Emirates was the latest Arab state to join the list, legalizing the medical procedure in 2016.

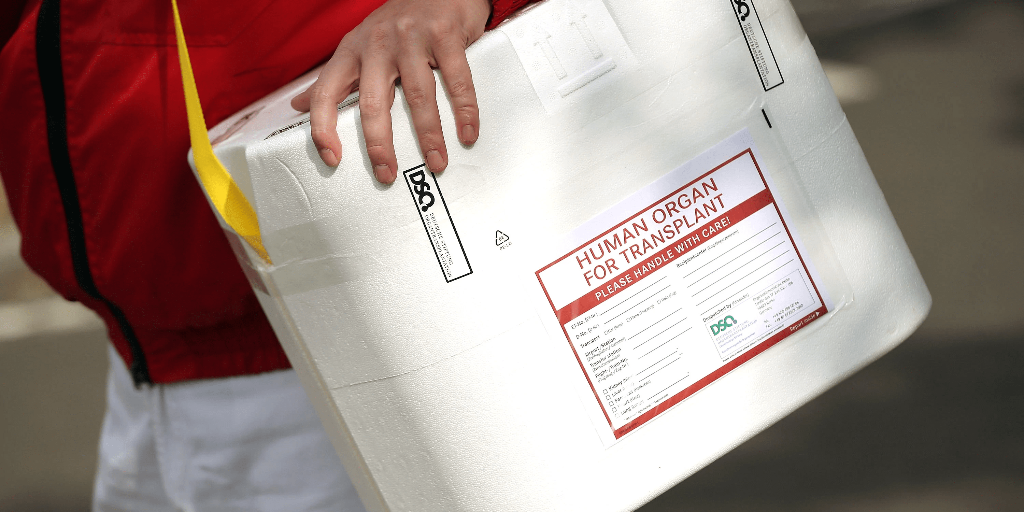

While the religious debate continues to exist, the issues arising from informal organ transplants – primarily trafficking and loss of lives – only continue to increase.

A case study conducted in 2016 by the British Journal of Criminology noted an increase in human organ trafficking in Egypt, with criminal sanctions and existing laws inadequate to address the growing problem.

Egypt’s underground organ market, manifested due to insufficient government regulations and rising demand in buyers from neighboring countries, was a blight on the country’s medical practice, according to the study’s data.

Unethical medics would smuggle organs of deceased patients out of hospitals. Other victims had their organs taken alive, experiencing kidnapping, forced surgery, and waking with a kidney scar.

Asha, a struggling Sudanese mother residing in Egypt, and a victim of organ trafficking, retold her trauma to The Guardian in 2019.

“I know it was Alexandria because I could see the [sea] from the taxi. Then I was in a room with medical equipment, but this is all I can tell you. They locked me in the room and told me to think of my children,” explained Asha.

The recruiters had initially promised her labor in Europe, later revealing that they plan to make her donate her organs for EGP17,000 (USD 2,000 at the time). If she did not comply, her kidney would be taken by force.

What is next for Egypt is the country’s plans to develop an electronic registry that records and waitlists patients in need of organ transplants, edging the country closer to a reality of ethical and legal organ transplants – one that does not require black market ventures.

Subscribe to the Egyptian Streets’ weekly newsletter! Catch up on the latest news, arts & culture headlines, exclusive features and more stories that matter, delivered straight to your inbox by clicking here.

Comments (0)