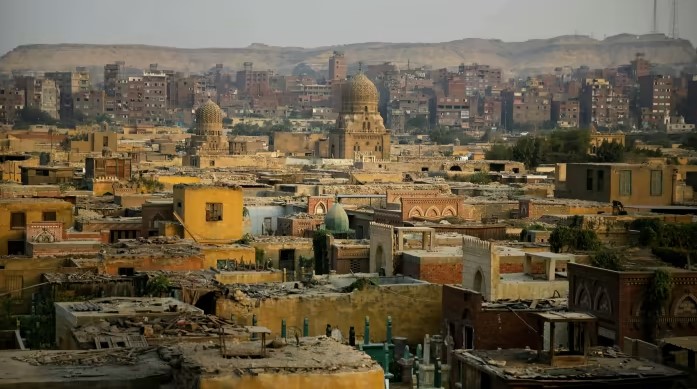

The heart of Egypt’s capital is home to an immense wealth of historically significant monuments and districts – from the ruins of Al-Fustat, to the Cairo Citadel, and Mamluk palaces dating back to the thirteenth century. Just as monumental is the debate over the preservation of this heritage amidst rapid urban development. Over the past week, the ongoing demolition of cemeteries in Historic Cairo, an area of the capital listed by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) as a World Heritage Site, has stirred public outcry and reinvigorated arguments over heritage conservation in Egypt. In the past two years, dozens of cemeteries in Cairo’s City of the Dead – a vast necropolis sitting at the foot of the Citadel and dating back to the seventh century – have been marked for demolition. The removals aim to make space for the construction of new main roads, to improve traffic flow in the congested capital. In 2021, UNESCO expressed concern about the demolition of tombs and mausoleums in the City of the Dead, noting that this “could have a major impact on the historic urban fabric of these parts…

Demolition of Historic Cairo Cemeteries Stirs Public Outcry in Egypt

June 2, 2023