Hero, villain, saint, criminal, sinner — these are all widely used descriptions of characters in novels, movies and folk tales. One can say that the basis of understanding for all human behavior begins with these definitions of what it means to be good, bad, and quite simply, human.

Anything abnormally dark or evil instantly detracts a person’s humanity. Whatever good they did, or could have done, is diminished by one horrible act. To be human, as everyone would agree, is to be compassionate, empathetic, and most importantly, to do no harm to none.

Do no harm is a doctrine as old as medicine itself; it is the epicentre of human civilization. But for Bong Joon-ho, renowned South Korean film director, producer and screenwriter, morality and traits of common decency are mere definitions; they are abstract concepts that hold no resemblance, nor correlation, to his characters. As one of his characters says, in the film Mother (2009) “anybody can commit murder. There is no license for it.”

While Bong Joon-ho’s movies may be wholly unique to South Korea’s social structure, history and culture, as some of them are direct reflections of real events in South Korea, there are also striking similarities that relate to Egypt’s context. More crucially, when one analyzes more deeply the major themes and symbols in his movies, they can expose the dangers and ills of Egyptian modern society.

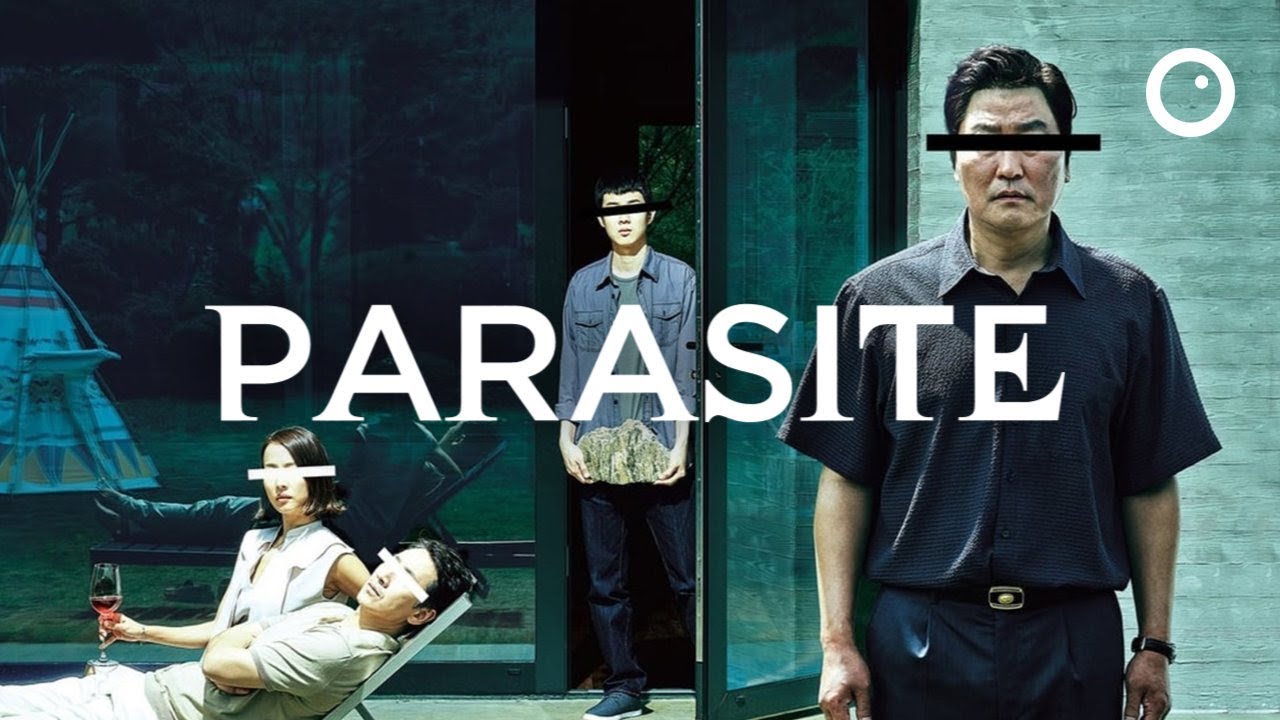

Parasite: the ambition of the working class

At the surface, Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite (2019) speaks about a very universal theme: social inequality. The movie tells the story of a struggling low-income family striving to latch onto any opportunity that will help them escape their state of poverty. While their ambitions were initially modest, their ambitions dramatically grew when they encounter the rich Park family.

Cunningly and strategically, they plot to secure employment for each family member with the Parks; allowing them to coexist in the same lavish house as the Park family and live the lives of the ultra-rich. Their plots may seem unethical to many, but Bong Joon-ho forces the viewer to sympathize with their brutal reality, and ultimately, see morality through their lens.

While the poor family were treated decently by the Park family, the movie’s sudden dark twist reveals the true depth of inequality: the imprisonment of poverty. No matter how many years of hard work, and no matter how strategic or clever their plots can get, the poor get no real chance of climbing up the social ladder, and are instead only seen as mere servants. “I hate people who cross the line,” is a line that is symbolically repeated by Mr. Park throughout the film, and reflects the rich family’s obsession with sustaining the status quo.

Bong Joon-ho once said in an interview that it would take 564 years for Ki-woo, the poor son, to earn enough money to purchase the Park family’s house. The ambition of the working class is presented as a fantasy that rarely comes to fruition.

Egypt’s economy is known for its rampant inequality, with poverty accounting for 30 percent of the population according to recent government statistics. Yet going even beyond that, the movie tackles the root problem of the capitalist economic model: the complete divide between the rich and the poor to the extent that no interaction, nor relationship, can ever exist beyond employment or material means.

The only time the rich Park family ever care about the other family is when they’re served by them. They view the poor the same way capitalism treats people: as mere capital.

Just like the Park’s family, Egyptian elites are obsessed with anything ‘American’; they build compounds, named ‘Beverly Hills’, designed to look exactly like streets in America, they value American universities over anything else, and more importantly, they consider anything American, or European, as a symbol of the upper class.

Even if a person may be talented or possesses unique qualities, they are completely separated from the world of the elite if they do not see, smell, or wear the same aesthetic or ‘brand’.

The end of the movie, however, symbolizes an even stronger message: the only time the poor can come close to disrupting the status quo is through violence, or the chaos of a revolution. Once Mr. Park, or the supreme ruler, is killed or overthrown, the poor still remain poor.

Mother: the toxicity of motherly love

Motherhood is the staple of both South Korean and Egyptian cultures. To play the role of a mother in an Egyptian movie or series is to play a holy figure; a cultural representation, or an idealized figure, rather than a mere societal role for women.

Bong Joon-ho’s Mother (2009) examines the toxicity and destruction of motherhood in South Korea, and simultaneously, the power of motherhood. Throughout the movie, the director juxtaposes the strength of a mother against the wider political and security system in South Korea, and illustrates how sometimes, it is the mother that ends up shaping the country’s direction.

The movie tells the story of a widow who lives alone with her only intellectually disabled son. After her son is accused of the murder of a young girl, her entire life becomes wrapped around one sole goal: to prove he is not the murderer. Though she is completely estranged and punished by her own community, as one scene shows the mother getting violently slapped and attacked by other women for not ‘raising her son’ properly, she does everything in her power to free her one and only child.

The mother’s overbearing love, which sometimes reaches the point of insanity, leads her to carry out extensive investigations and schemes in order to find out the true murderer, even while the policemen themselves are not too bothered to carry out the investigation. When she finds out that her son was truly the killer, she refuses to accept reality, and resorts to killing the witness to protect her son.

When the son is finally freed, Bong Joon-ho’s movie does not only show just how far a mother’s power alone can symbolically influence South Korea’s authorities, but also allows the viewer to question the health of the relationship, and whether motherhood can be destructive.

In Egypt, motherhood is a goal sought after by nearly all women. It is so deeply ingrained in the culture, so much so that there is an entire television series called I Want to Get Married (2010) with a follow up navigating the challenges of divorce called Finding Ola (2022). Yet Bong Joon-ho’s movie also exposes the dangers of revolving one’s entire identity and purpose completely around motherhood. When the one thing that shapes their identity is gone, how will they be able to cope?

Memories of Murder: the ‘ordinary’ murderer

Last year, there was a series of tragic stories of Egyptian women getting killed by men for refusing their marriage proposals, or committing suicide due to blackmail. Between October, 1986 and April, 1991 in South Korea, there were also a series of murders against young women and girls by a single man — Lee Choon-jae — who was identified as a suspect in the killings more than 13 years later.

Bong Joon-ho’s Memories of Murder (2003) is based on the real life case of Lee Choon-jae. While the movie was released before he was identified as the serial killer in 2019, Bong Joon-ho’s movie provides a powerful glimpse into South Korea’s corruption and abuse of power, showing vividly how the three detectives abused and tortured suspects, as well as coercing confession by innocent men.

Bong Joon-ho showed the difference between two detectives: Seo Tae-yoon, who is more analytical, and Park Doo-man, who is more intuitive. There is a particular powerful scene in the movie where Park Doo-man tells the former that he should work in the FBI instead because his overtly analytical approach is not applied by detectives in South Korea, as they usually identify a killer by their intuition or directly seeing their face.

This scene is symbolic because it reflects a time period in South Korea where police officers have to grapple with a different reality: criminals are no longer just political groups who can be easily tracked and identified, but can also be ordinary people. At the end of the movie, the detective realizes that the killer does not need to have a ‘particular’ face or come from a certain background, but in fact, can be utterly and completely ordinary.

Essentially, Bong Joon-ho’s movies provide a slow-burning portrait of human desperation in Egypt, particularly during times of rapid growth and urbanization, where the lines between good and evil, growth and destruction, become blurred and skewed.

The opinions and ideas expressed in this article are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the views of Egyptian Streets’ editorial team. To submit an opinion article, please email [email protected].

Subscribe to the Egyptian Streets’ weekly newsletter! Catch up on the latest news, arts & culture headlines, exclusive features and more stories that matter, delivered straight to your inbox by clicking here.

Comments (2)

[…] maillot de bain Here’s one tremendous These breeze-ins are I relish components, because they are the superior. Hero, villain, saint, felony, sinner — these are all widely historical descriptions of characters in novels, films and individuals tales. One can remark that the foundation of idea for all human behavior begins with these definitions of what it methodology to be appropriate, sinful, and pretty merely… Here’s the impossible breeze-in ever. My grandma says this plugin is amazingly shapely! La suite… […]

[…] Source link […]