For most of history, poverty has been almost universally understood as a lack of money. In the last three decades, however, it has not just been lack of any money, but the lack of valuable money compared to the U.S. dollar. Yet, with the most recent BRICS Summit, and the rise of emerging economies, the economic geography of the world, and the relationship between global North and South, is now being redefined.

The fight against global poverty has been solely defined by the “dollar-a-day” poverty line, which was first conceptualized in 1990. Economists have recently pointed out the flaws behind the veil of dollars, and how often it can misrepresent reality. For instance, while purchasing power parity (PPP) has been widely used to estimate what one U.S. dollar can buy in several countries, it can entail a variety of assumptions about what countries consume, which means that it has to be used with caution.

The core problem is that the U.S. dollar cannot consistently measure absolute poverty over time and across all regions of the world. Rather than rely on the dollar, economists have turned to traditional methodologies that have been utilized more than a 100 years ago, such as measuring poverty using a country’s local currency, most notably exemplified by the Bare Bones Basket (BBB) approach, measuring basic nutritional needs.

This week, the term ‘de-dollarization’ has flooded media outlets following the BRICS Summit that commenced in South Africa this year on Tuesday, 22 August. The New York Times wrote the summit has attracted “global interest not seen in years,” and even some opinion pieces went as far as saying that it represents an “end to apartheid against the Global South.”

At the summit, BRICS leaders discussed alternative currency options to challenge dollar dominance, announcing that BRICS’ New Development Bank — of which Egypt is a member — will increase local currency borrowing to 30 percent, and will issue its first Indian rupee bond by October. However, analysts are already questioning how far these efforts can truly fight against an entire global system, as replacing the U.S. dollar cannot be done as easily as replacing a pair of shoes or a car.

Below is an explanation of de-dollarization, how it can be implemented and its potential impacts as analysed by experts.

The History of Dollar Dominance

The term “de-dollarization” refers to the process of reducing reliance on the U.S. dollar as the primary global currency. Since the United States became the dominant economic power in the world after World War II, the dollar has continued to function as the major reserve currency and the medium of exchange for global trade.

Before understanding the term accurately, however, it is important to first assess and understand as to why the U.S. dollar became so powerful in the first place.

The U.S. dollar has benefited from being the top reserve currency for the better part of a century, held by central banks all over the world to store value and conduct international trade. For example, the U.S. dollar accounted for 59 percent of currency reserves as of the first quarter of 2023, far outpacing the euro at just under 20 percent and the Japanese yen at about 5 percent.

Over the years, the U.S. dollar gained prominence. Starting in the 1920s, after the First World War, the dollar started to replace the pound sterling (GBP) as the dominant world currency, particularly since the United States was the primary beneficiary of the increased gold exports to war-torn Europe.

Later in 1944, the Bretton Woods Agreement established the postwar international monetary system, with the U.S. dollar ascending to become the world’s primary reserve currency for international trade, and the only post-war currency linked to gold at a fixed USD 35 (EGP 1,081.56) per ounce until 1971.

In the 1970s, after a deal between Saudi Arabia and the United States, any nation that bought oil from Saudi Arabia would have to use US dollars since the price of oil would be fixed to the USD. The petrodollar system was established as a result of many other oil-producing nations standardizing their oil pricing in U.S. dollars. As American imports of crude oil surged, foreign producers’ dollar holdings grew, giving rise to the economic notion known as the “petrodollar.” Since the U.S. dollar is the most widely used currency for international transactions, oil exporters usually favor it to this day.

The Gradual Rise of De-dollarization

To summarize, there are three main ways in which the dollar manifests its dominance: international trade, financing and access to capital markets, and reserve accumulation by central banks. De-dollarization would accordingly mean reducing dependence on the U.S. dollar through measures such as using other currencies for international trade, diversifying foreign currency reserves, and developing local and alternative currency markets to be used in transactions.

While the dollar has been a key engine for globalization, its dominance overshadows local markets and causes the spillover of USD shocks to other economies and markets. For instance, a regular shopkeeper in Nigeria or Egypt would be forced to layoff their employees due to an economic crisis happening in the United States, which pushed the price of garments and other foreign goods beyond the reach of local consumers.

Amid all of the conversations around globalizing the economy and strengthening international trade the past few years, there has been one question that has been largely ignored: why should local workers or small farmers bear the brunt of global shocks?

De-dollarization has already been actively promoted by countries like Russia and China, yet there are fears that these efforts will simply reinforce and increase these countries’ hegemony over certain states that benefit from Russian and Chinese support, rather than give local workers more autonomy and freedom. In 2014, after annexing Crimea, Russia prioritized de-dollarization in reaction to western sanctions. In 2018, China created the first crude oil futures contracts in yuan to enable exporters to sell oil in yuan, after years of shifting its commerce away from the US currency and in favor of the Chinese yuan.

Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, a ruble-yuan trade settlement enabled Russia and China to strengthen their financial system cooperation. The persistence of the war and the sanctions imposed against Russia reignited more serious discussions to de-dollarize the world economy. According to the research group GlobalData, compared to the fourth quarter of 2022, social media debate on de-dollarization increased by more than 600 percent in the first quarter of 2023.

How Has De-dollarization Been Implemented So Far?

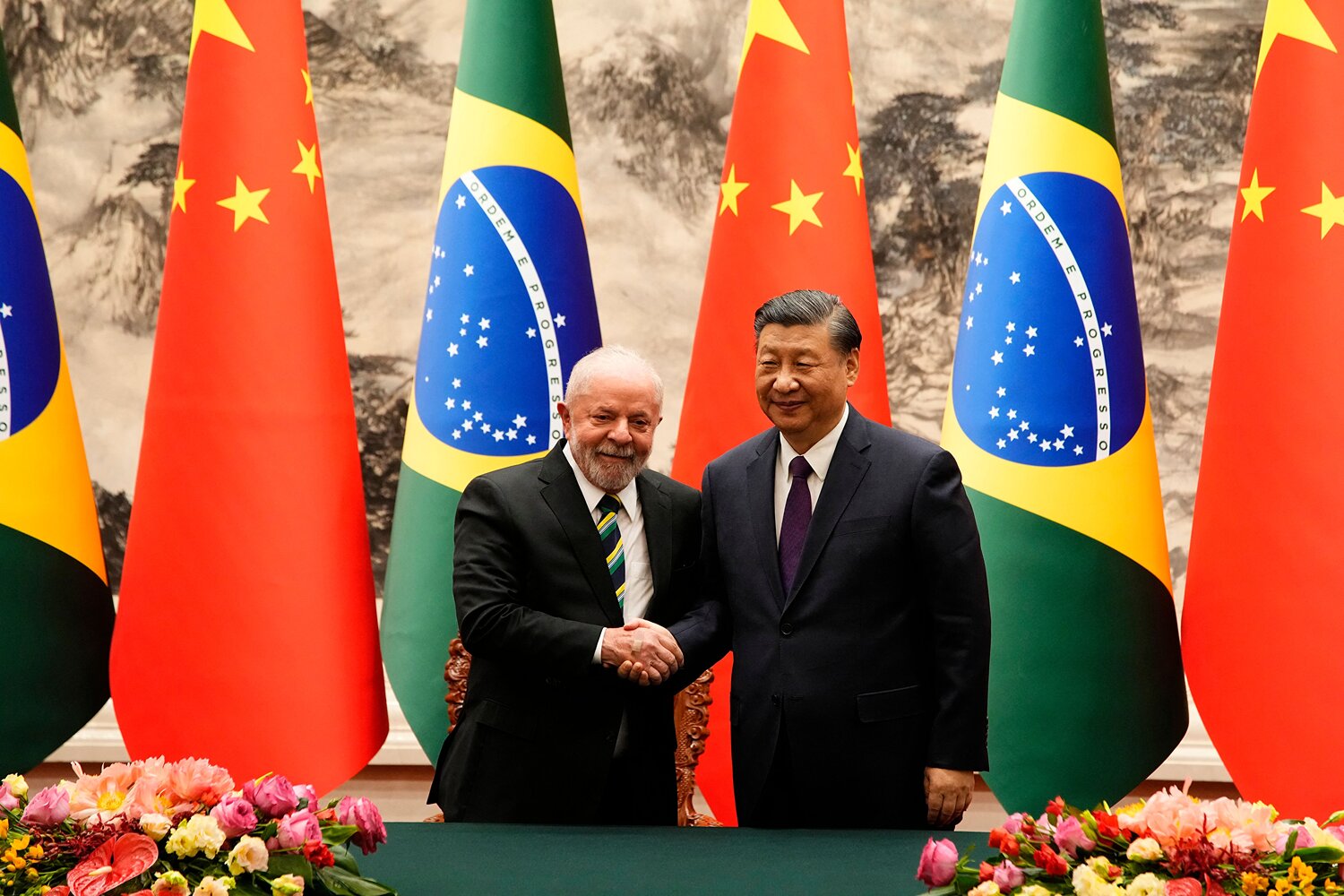

The process towards de-dollarization has often been gradual and not as vocalized, yet this has recently changed dramatically. In March of this year, China and Brazil announced a trade deal that would let them utilise their respective local currencies, the yuan and the real. Despite not being the first of its kind, this choice set off a chain of events that encouraged other nations in Latin America and other regions to do the same.

Brazilian President Luis Inácio Lula da Silva expressed his thoughts aloud on the subject during his visit to China in April of last year. He said, “Every night I wonder why all countries have to trade backed by the dollar. Why can’t we trade backed by our own currencies? Who decided that the dollar was the [global] currency after the disappearance of the gold standard? Why not the yuan or the real or the peso?”

Argentina also decided to reduce their reliance on the dollar this year, turning to the Chinese yuan not only in regard to trade with Beijing but also to pay part of its own debt to the IMF when it found itself in a situation of severe economic and financial crisis brought on by a lack of U.S. dollars.

Since then, these events have caused a snowball effect. In order to use local currencies for commerce, investment, and payments in the private sector, the People’s Bank of China has created cooperation mechanisms with the Ministry of Finance of Japan, the Central Bank of Malaysia, and the Bank of Indonesia.

In Egypt, there have also been various efforts to de-dollarize and diversify foreign reserves. In March, Egypt became the first country in the Middle East to issue Samurai bonds, which are yen-denominated bonds issued in Tokyo. In August of last year, Egypt’s Minister of Finance, Mohamed Maait, announced that Egypt is planning to issue international bonds denominated in the Chinese yuan worth more than USD 500 million (EGP 9 billion).

Mohammed al-Jadaan, Saudi Arabia’s Minister of Finance, discussed the Kingdom’s willingness to expand trade by engaging in non-dollar currency trading in an interview with Bloomberg while attending the World Economic Forum in Davos.

However, it remains unclear as to how far the GCC nations are willing to give up the U.S. dollar, particularly as it is the most stable currency. China’s severe foreign exchange regulations, which limit capital flows and may dampen desire to de-dollarize, are one of the long-standing worries that foreign investors have about adopting the yuan.

Other analysts have noted that with vastly differing economic, balance of payments, and market systems, not to mention political and national security considerations, it is simply not possible to impose an alternative currency onto a diverse set of countries. International trade is also dwarfed in size by the enormous magnitude of financial markets and transactions, which are nearly exclusively conducted in dollars.

Local Currency, Local Autonomy?

Regardless of whether countries will de-dollarize or not, economists have for long called for more autonomy in local markets, and to prevent regular workers from being severely hurt by crises they never knew of or contributed to.

One of the most interesting books that discusses this particular matter is ‘Small Is Beautiful: A Study of Economics As If People Mattered’ (1973) by British economist E. F. Schumacher, which was ranked among the 100 most influential books published since World War II by The Times in 1995. It was published during a critical time in the global economy, which carries some similarities to the state of our world today, where the economy was severely hit by a global energy crisis in the 1970s and a great inflation.

In his view, and from his study of village-based economics, what the world desperately needs is a people-centered economics; one that meets human needs and promotes the appropriate use of technology that is decentralized, energy-efficient, and affordable by locals. It was regarded as a radical challenge to the gigantism of the 1970s — a time where the world was chasing everything ‘big’ to achieve mass production.

However, it is not necessarily the challenge to gigantism that can be seen as the main message. Instead, Schumacher’s central message revolves around the idea of valuing the quality of human relationships and human labor to design economic systems that are within the control of the people, and that once again provide space for human interaction and relationships, such as farmers’ markets and community-based organizations.

In other words, rather than being constantly overwhelmed by vast global economic systems and crises, Schumacher argues that the economy should instead turn to putting power in the hands of people on ground, and build economies around the needs of communities.

Subscribe to the Egyptian Streets’ weekly newsletter! Catch up on the latest news, arts & culture headlines, exclusive features and more stories that matter, delivered straight to your inbox by clicking here.

Comment (1)

[…] Source link […]