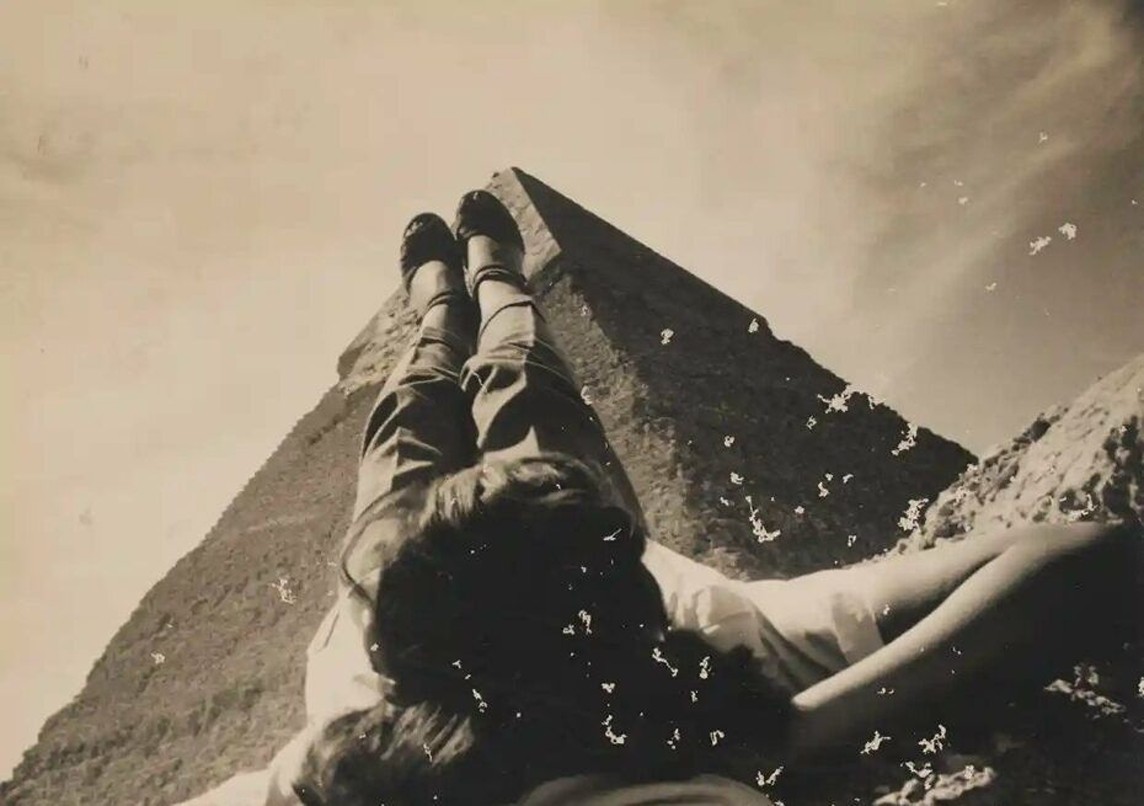

“Have you seen the Egyptian Museum? Much of pharaonic art is surrealist,” wrote Kamel el Telmissany, an Egyptian surrealist artist closely associated with the Cairo-based Art and Liberty Group, in a 1939 journal entry.

As el Telmissany insightfully pointed out, surrealism — an artistic movement that delves into the subconscious, while challenging conventional perceptions of reality — was not “specifically a French movement,” as many art critics often claim. Instead, it goes beyond nationality and religion, embodying a universal movement that has existed for millennia, even in the ancient times of the pharaohs.

Though surrealism has evolved over the years, its essence — its primary goal — has remained consistent: to explore the subconscious realms of human emotion, thought, and action, and create art that illuminates rather than obscures, and liberates rather than confines.

‘Degenerate’ Egyptian Art and Sexual Freedom

The year was 1938, a time marked by the growing spread of totalitarianism, a political system that imposes control on all aspects of human life, and fear across the globe, with Hitler’s Germany at its epicenter.

In this climate, art faced intense repression, and was labeled as “degenerate art” by the government and art critics in society. Under these authoritarian regimes, art was stripped of its ability to inspire and provoke. Instead, it became a tool to further political and nationalist goals, rather than be cherished for its power to challenge, to evoke emotion, and, above all, to connect with people on a much deeper level.

That year, a collective of Egyptian surrealists united to take a stand against these authoritarian regimes. They released a manifesto in 1938 titled “Long Live Degenerate Art,” a bold statement in defiance of the art critics and the Nazis. The manifesto can be viewed as a reinterpretation of the Egyptian phrase “hawareek” (meaning “I will show you”), but with an artistic twist.

Instead of rejecting the label “degenerate,” the artists adopted it with pride, turning it into a symbol of defiance. They used it as a badge of honor, channeling it into art that was boldly unconventional and most importantly, unapologetically degenerate. This marked the official founding of the Art and Liberty group, with the manifesto signed by 37 individuals, uniting all the Egyptian surrealists, including writers and photographers.

One might ask: what exactly is degenerate art? Is art not supposed to be beautiful? This is the very question the surrealists sought to challenge. They opposed the idea that art’s sole purpose was to uplift and entertain, to never confront or reveal life’s darker realities. As El Telmissany once put it in one of his articles, “art will not be a tool for the pleasure of people to bring joy to their idle minds.”

Since the founding of Art and Liberty group, the surrealists organized numerous exhibitions and launched Al Tatawwur in 1940, an Arabic-language literary and cultural magazine. It was the first avant-garde, surrealist, and Marxist-libertarian publication in the Arab world. During its brief existence, Al Tatawwur boldly tackled subjects like sex and women’s sexual freedom.

Some scholars have even argued that its exploration of sexuality was integral to the liberation of Egypt from colonization, subverting the dominant narratives of the regime and creating space for Egyptians to engage more freely with taboo topics. Research has also shown significant connections between the persistence of colonial governance and the control of sexuality.

This regulation serves not only as a crucial mechanism of social control, but also plays a key role in contributing to the construction of the European identity by defining and differentiating what is deemed normatively sexual in European terms. To decolonize, then, means to critically examine ourselves, which calls for a deeper understanding of who we are —not only as citizens of a nation, but as human beings.

This call for humanism, which el Telmissany consistently championed in his writings, lay at the core of Egyptian surrealism. His aim was to shed light on and “liberate people from the false night” of ignorance and tyranny that had overshadowed them.

The call also sought to empower Egyptians to forge their own distinct sexual identity, independent from European sexuality, and to confront their darker, often overlooked, realities.

Through their paintings, many surrealist Egyptian artists placed a strong emphasis on the raw aspects of human nature, often focusing on the body in various forms, highlighting the body as a key element of identity while also exploring its potential for exploitation.

Ramses Younan, a leading figure in Egyptian art and a co-founder of the Art and Liberty group, exemplifies this theme in his painting Untitled (1940). The painting depicts a distorted woman sleeping against a backdrop of wooden panels, with exaggerated, disproportionate breasts and arms, underscoring the objectification and exploitation of the female form.

Fragmented bodies also frequently symbolized oppression. Inji Efflatoun’s Girl and Monster (1942) is another powerful example, with its haunting depiction of contorted figures. The distorted, trapped bodies reveal the anguish of women driven into sex work by the harsh realities of war and poverty.

While some may label these paintings as ‘degenerate,’ this was a deliberate choice—to provoke and challenge societal norms. They aim to make viewers question their perceptions of their own bodies and those of women, as well as to confront war and poverty.

Sorrow and Struggle

Egyptian surrealists also did not stray far from reality.

While the term ‘surrealist’ may suggest a detachment from the real world, much of their work is actually deeply rooted in it. In other words, surrealism delves into the unconscious emotions and thoughts that influence daily life, exploring how sorrow and struggle manifest in various forms.

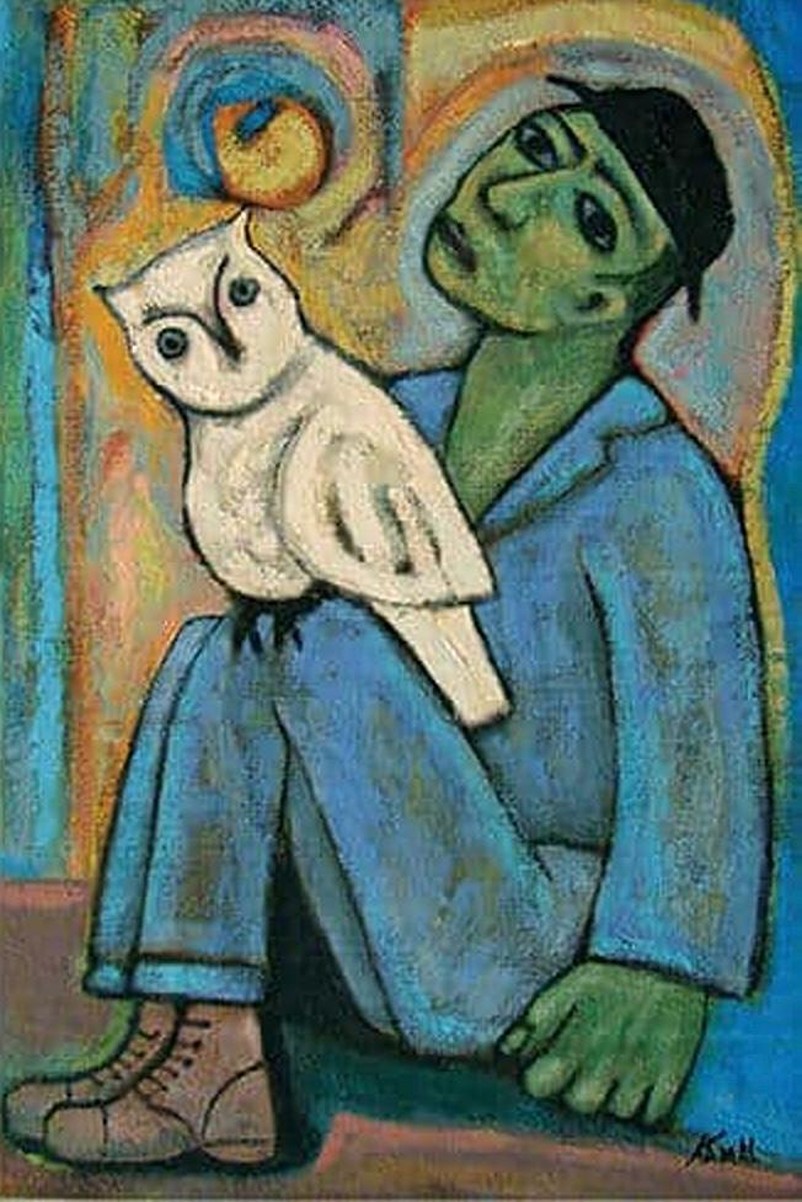

Kamal Youssef, one of the members of the Art and Liberty group, focused on the everyday life of Egyptians, which is often paired with symbolic motives, such as animals or religious iconography. For example, in his painting Reverie (1986), an Egyptian man gazes into the distance, his expression almost hypnotic or somber, while a white owl perches on his lap. The scene exudes a sense of mysticism and exoticism, yet it also invites deeper contemplation, prompting the viewer to ponder the man’s inner thoughts and emotions.

His paintings also often highlighted the struggles of Egypt’s working class, particularly those who labored on the land. He created several works depicting distorted, anguished figures seated before empty bowls, symbolizing hunger, as well as others showing characters bent under the weight of their emotional burdens. While some of these paintings may feel overwhelmingly bleak, their stark, sorrowful imagery is designed to evoke the unconscious, darker realities of people’s lives.

Many Egyptian surrealist paintings sought to highlight the darker aspects of Egyptian history, especially its pharaonic past, rather than romanticizing or glorifying it. Pharaonic imagery had often been co-opted as government propaganda, so when artists from the Art and Liberty group employed such symbols, they typically distorted them to show their defiance against the regime.

For instance, Ramses Younan’s Untitled (1939) painting depicts the body of a goddess twisted into unnatural angles, presenting a fractured and more vulnerable image of Egypt. This painting does not necessarily aim to vilify the country, but rather challenges the dominant narrative of the regime, which frequently co-opted ancient symbols for political purposes, rather than for artistic expression.

In the years that followed, the surrealist movement in Egypt underwent a major transformation after the country’s nationalization, particularly as Egypt emerged as an independent state free from colonial rule. This shift gave rise to new art collectives, such as the Contemporary Art Group and the Modern Art Group, which aligned more closely with the ideals of the newly independent nation. Abdel Hadi el-Gazzar, an Egyptian painter and member of the Contemporary Art Group, created The Charter (1962), a work that honors Nasser’s Charter, a socialist manifesto advocating for the revolutionary redistribution of land to Egypt’s peasants.

While the surrealist movement originally had a strong Egyptian influence, today it has evolved into a highly individualistic style with a more global reach.

In Egypt, several art centers and museums, such as the Museum of Modern Egyptian Art, now provide platforms for contemporary artists. What truly set the Egyptian surrealists of the past apart from today’s artists was their shared ideological commitment and collective spirit of rebellion.

These Egyptian surrealists brought forth a new approach to art, one that went beyond personal expression to adopt a collective voice—unapologetic, free, and defiant—playing a pivotal role in Egypt’s liberation from colonial rule.

Comments (0)