It does not matter if you are in your bedroom, squeezed on a crowded bus, walking through the streets, or sitting on a tiny balcony, because once Raï’s melodies begin to pour into your ears, your body responds without hesitation.

Suddenly, you are on your feet, swaying, moving, and maybe even smiling without meaning to. There is a certain kind of pull in this North African music, a certain energy that feels like a return to an atmosphere reminiscent of a time that was both ancient and raw. It feels like it was created to awaken the body as much as the ear, with your body becoming an instrument within the music itself.

And this is because Raï music was always born in raw, unpretentious spaces, sung and played in local cafés, smoky cabarets, and the everyday corners of Algerian life. It emerged in an era when the body was understood as its own instrument, and when music was made to bring people together in one room, moving in sync, fully swept up in the emotion of the song.

While the pop version of Raï music, popularized globally by figures like Cheb Khaled and Cheb Mami, has long captured the attention of international audiences, the genre’s roots are far more raw, rebellious, and complex.

Born in the 1920s in the cabarets (nightclubs) and working-class cafés of Oran, a bustling port city in colonial Algeria, Raï music first emerged as a voice of resistance. It tackled taboo subjects head-on, such as desire, sexuality, partying, and freedom from colonial rule, at a time when such themes were considered dangerous.

For years, Raï was pushed to the margins, criticized by religious leaders and political figures alike. And yet, it endured, morphing and modernizing into different sounds, ultimately becoming a cultural legacy.

Today, a new generation of artists is returning to those roots, reconnecting with the original rawness of Raï music. In France, French-Algerian rapper Danyl has made this fusion a cornerstone of his music, while French-Algerian artist Elias is helping drive the revival forward with his modern take on 90s-style sentimental Raï.

In his latest single, Plus Se Quitter (No More Leaving Each Other, 2025), produced in collaboration with Berlin-based artist Zouj, Elias revives the grit and soul of 90s-style sentimental Raï while blending it with a modern sound. The track delves into themes of exile and long-distance love, providing today’s youth a fresh yet familiar way to connect with the spirit of classic Raï.

“We’re losing the respect we had for the pioneers of the genre,” Elias tells Egyptian Streets. “So that’s really what I tried to do with this song. I wanted to rethink traditional Raï, keep the melodies and the sounds, but bring them into a world that feels true to today.”

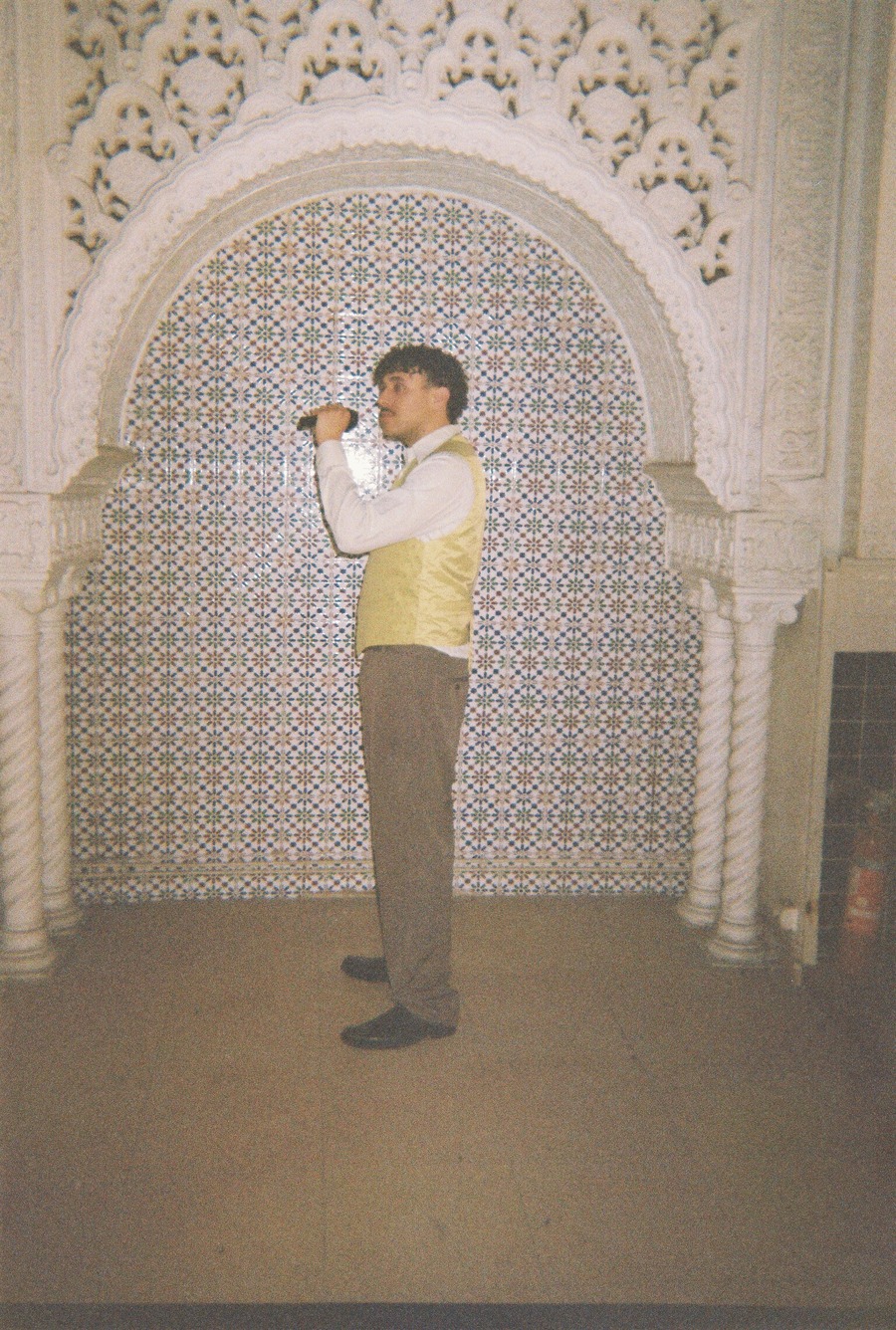

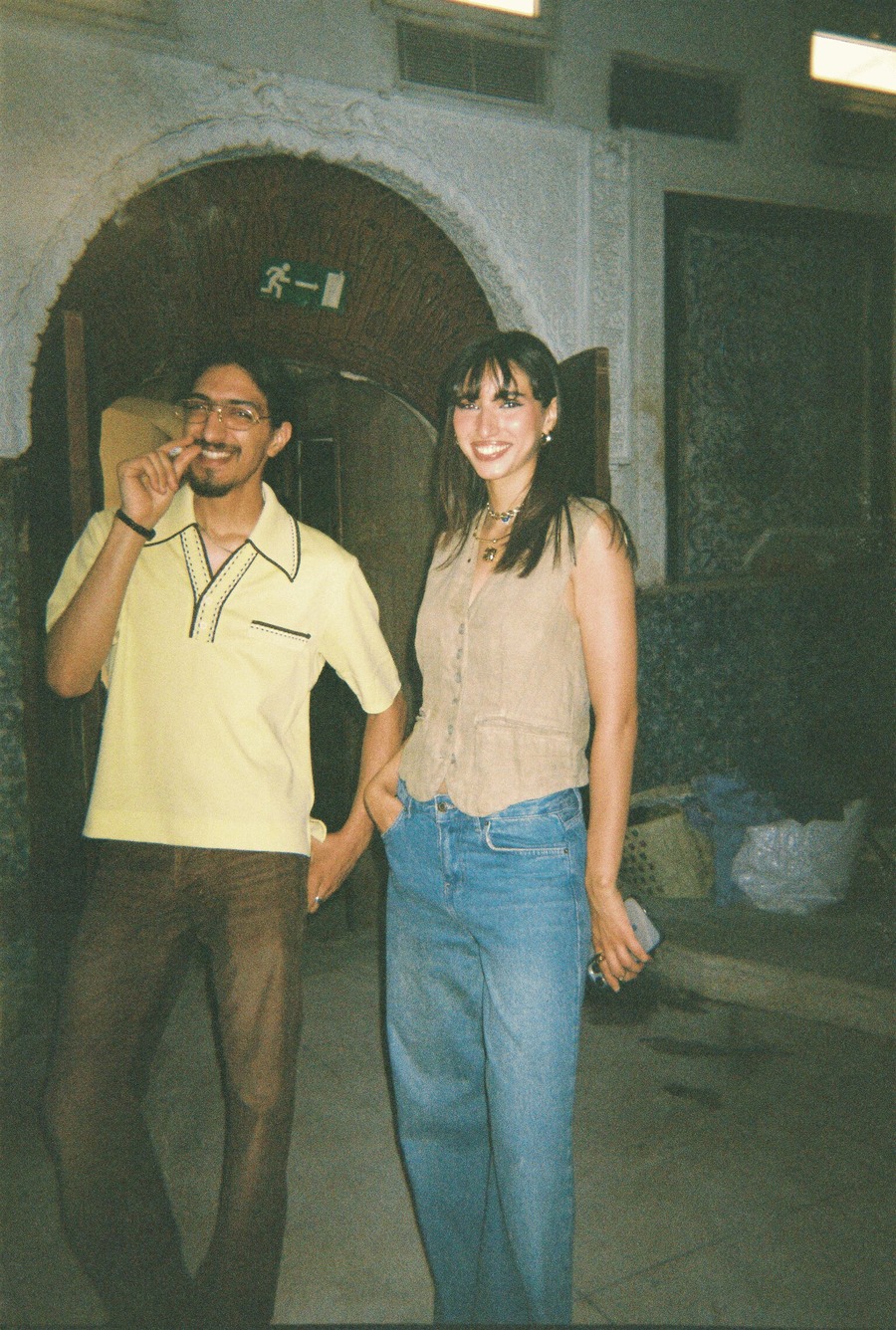

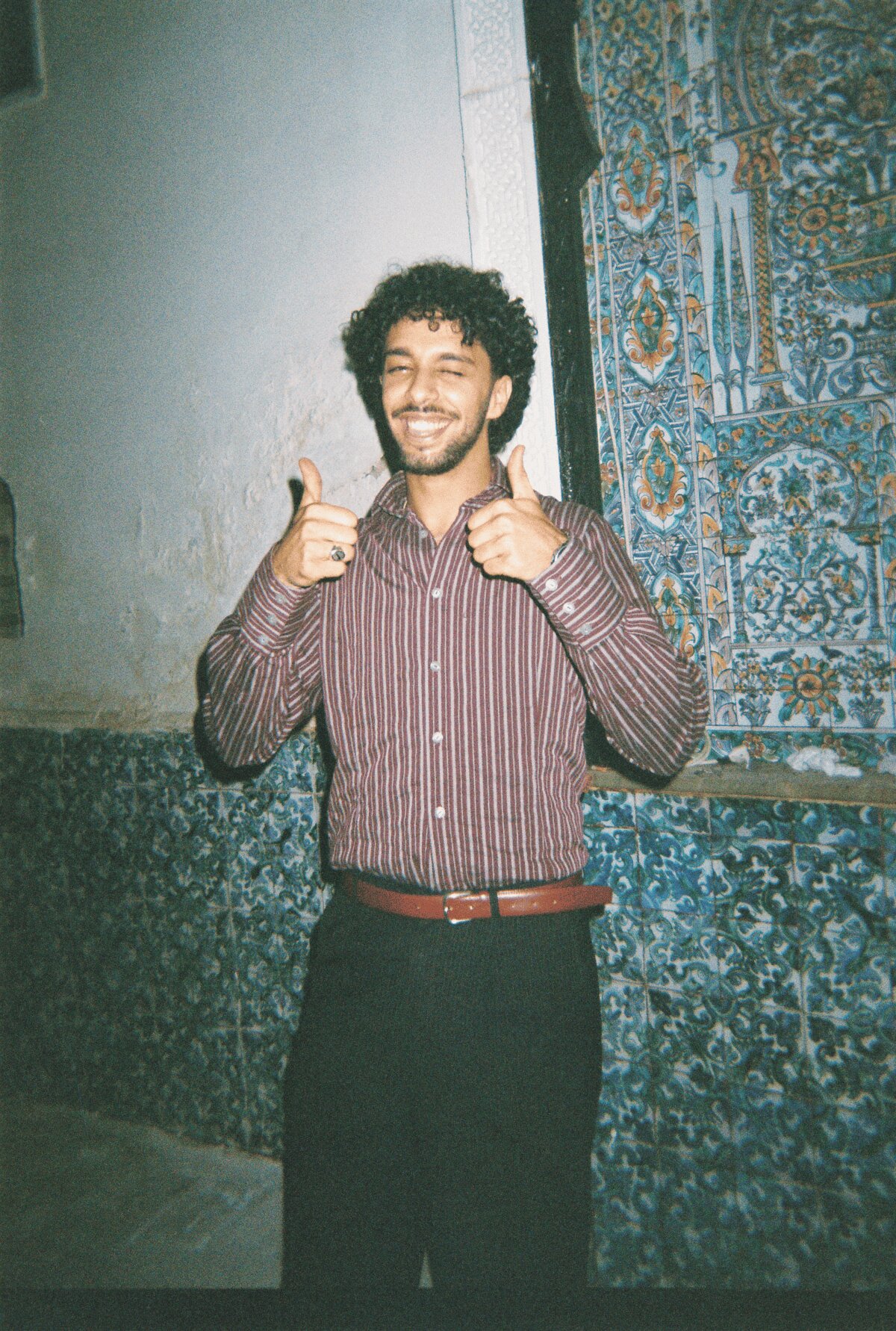

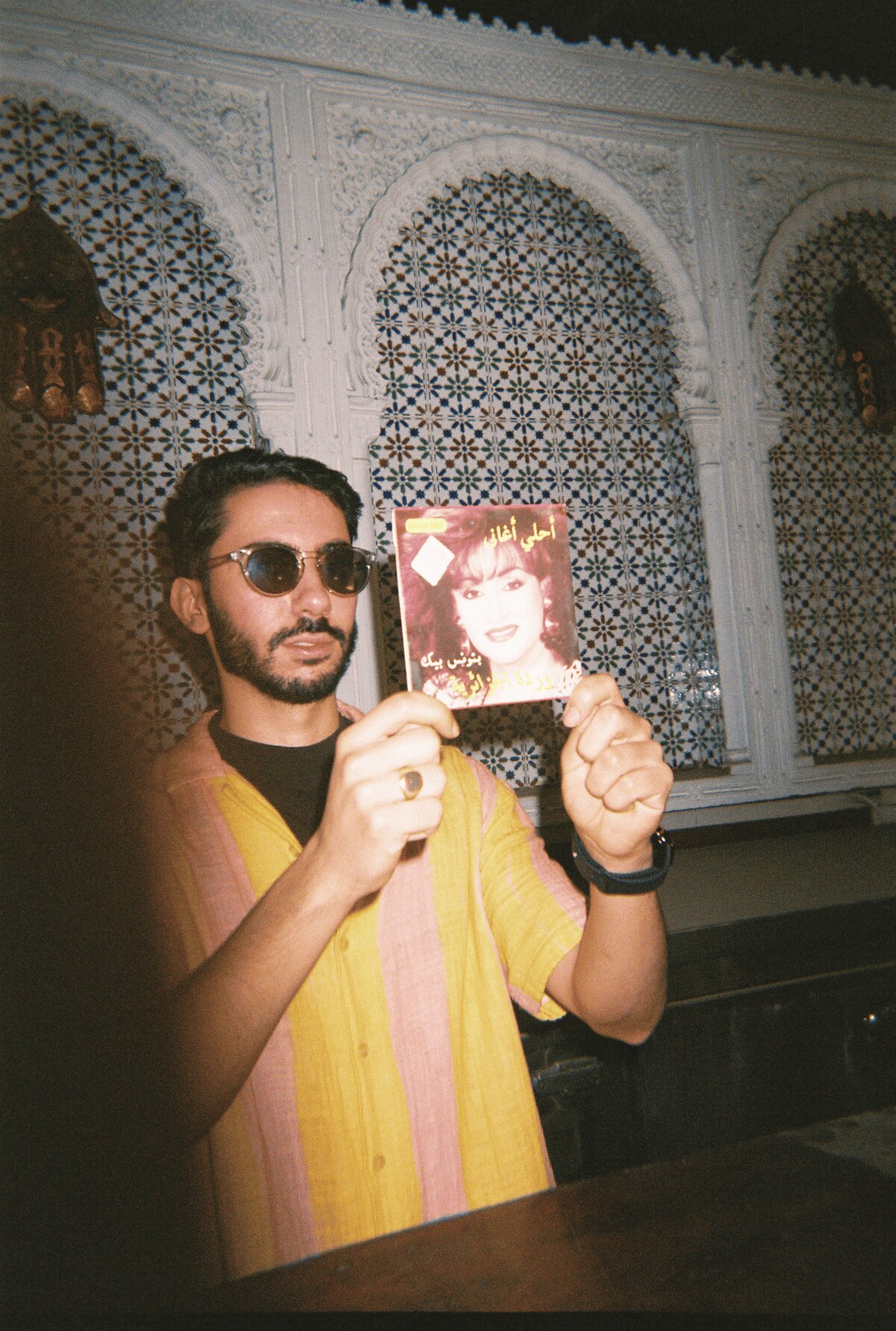

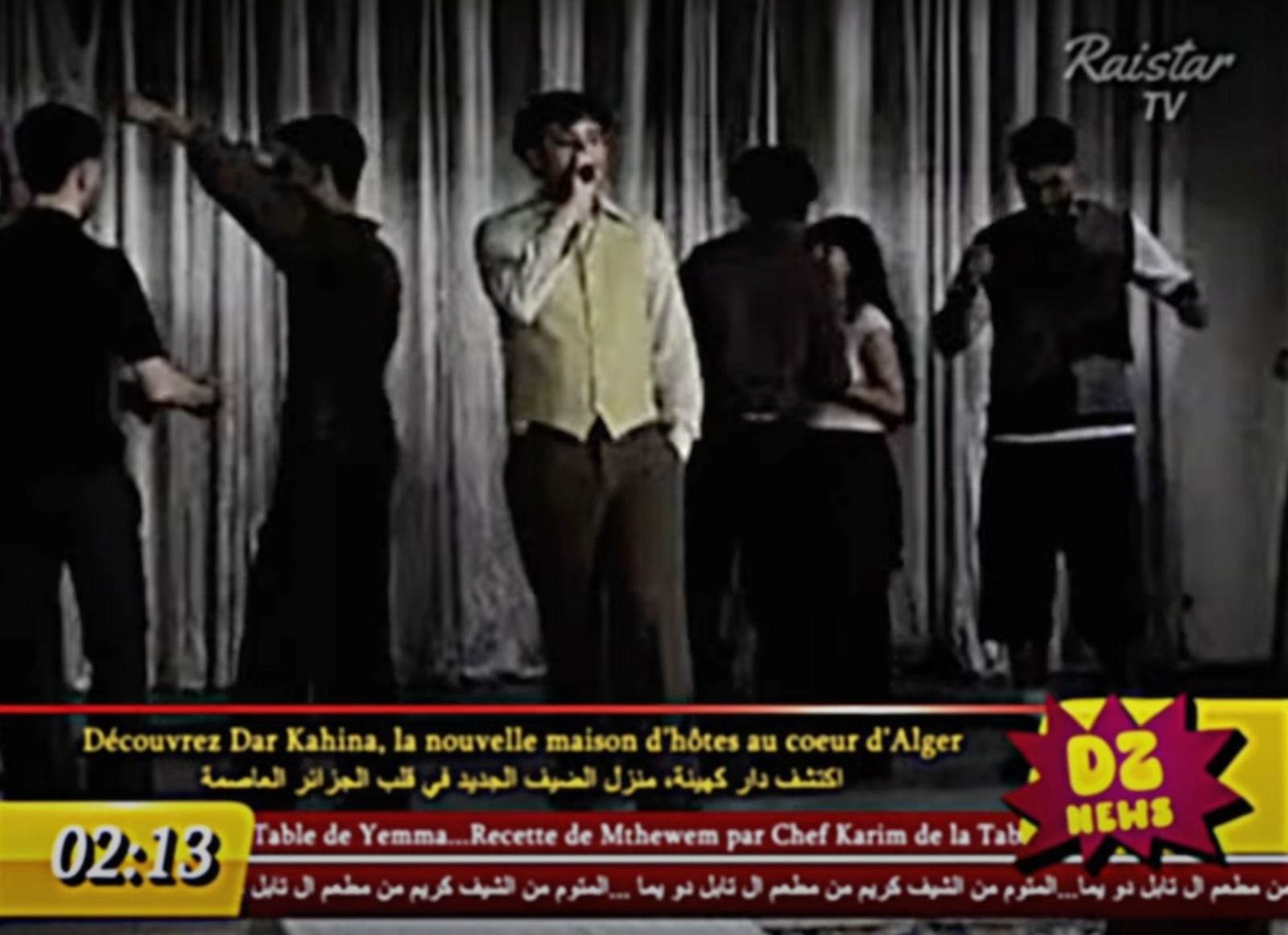

Filmed at Koutoubia, a legendary cabaret in Algiers that once hosted Raï icons like Cheb Mami, the music video revives the aesthetic of 90s Algerian television. From the retro visuals to the traditional fonts and graphic design, every detail serves as a heartfelt tribute to that iconic era.

It also became a revival of cultural memory and place. The venue, closed for years, was reopened especially for this project, turning it into a rare moment to reconnect with the very spaces where Raï was first born and lived.

“Before performing there, I didn’t know about its cultural impact,” Elias says. “I’m from a city called Annaba, far from Algiers, so I didn’t grow up with the same references. A friend helping with the video said, ‘I found this incredible location,’ and once I did my research, I realized how iconic it was.”

Passersby even paused with curiosity, some asking if they could step inside, a space many had never entered before. “A woman who passed by during the shoot told us she’d never dared to step inside when it was open because of the stigma around Raï,” he says. “She asked if she could just look around, just once before someone buys it and turns it into something else.”

The venue may have stood empty for years, but its walls still echoed with history, alive with the memory of what once was. With a Gen Z cast and an electric energy in the air, the shoot transformed into a moment of cultural reawakening in a place still echoing with the weight of its past. “Even without tables or music, you could still feel it. The spirit, the culture, it was all there,” he adds.

As someone born and raised in France with Algerian roots, Elias carries themes of exile, identity, and longing deep within his sound. His latest work pays tribute to the sentimental, melancholic essence of 90s Raï music, which could also be dubbed as his own love letter to the 90s, to nostalgia, and to long-distance love.

“I wanted to highlight the social reality of that time,” he explains. “There was a wave of first-generation Algerians coming to France, and a lot of couples were living apart, because husbands were moving to France to earn money, while their wives stayed in Algeria. I wanted to sing about that moment of separation, the hope they held onto, and the belief that one day they’d be reunited.”

It is also a personal story, one that mirrors his own family’s experience and reflects a broader reality in Algerian culture. “When my parents met, my mom was living in France and my dad was still in Algeria,” he shares.

“So for me, long-distance relationships were never unusual, they were just part of life. It is something that has become normalized in our culture. I wanted to honor that experience, not just through the lyrics, but through the sound, the aesthetic, and the feeling of that era.”

While music has long been a vessel for migrant expression, with the example of the American Blues, what sets the Algerian migrant experience apart is its recency. With independence gained just over 60 years ago, the sense of being a ‘stranger’ or living in exile still lingers heavily.

For many Algerians, and North Africans more broadly, this feeling is still ongoing, as it stems from generations of having their identities shaped, suppressed, and distorted under colonial rule, leaving a lasting search for selfhood in its wake.

“I think my lyrics often touch on exile because it’s part of my existence,” he explains. “The Arabic word ghorba (alienation) cannot really be translated into French or English. It’s a feeling, not a place. And it’s something that even people born in the diaspora feel. It lives in you.”

That feeling is especially potent in Algeria, where the legacy of French colonialism remains deeply felt. “Our colonial history only ended a little over 60 years ago,” Elias says. “A lot of people alive today either lived through the war or left the country back then. So exile is still a huge part of our identity, even if we don’t talk about it every day.”

Raï music itself emerged as a form of resistance to that colonial past. In the post-independence years, artists like Cheb Khaled turned Raï into a tool for reclaiming cultural identity, a counter to racism, censorship, and the pressure to conform to Western or sanitized versions of North African and Arab identity.

Whether through lyrics, cassette tapes, or underground radio, they used sound as a weapon to assert their presence and push back against both marginalization and extremism, building a new identity from the fragments left behind.

What makes Raï music continue to resonate so deeply with today’s youth, perhaps even more than with older generations, is its honest reflection of the struggle to navigate in-between identities. It is a tension that still defines the lives of many young people, especially as the Middle East remains shaped by the aftershocks of war, displacement, and fractured histories.

In this search for meaning, Gen Z is looking back, revisiting the sounds of the ’90s and turning to the wisdom of their ancestors to make sense of how colonial legacies still ripple through their present.

Elias observes that today’s youth are connecting with Raï in ways that are distinctly different from generations before them. “Now it’s accepted,” he says. “You hear it on the radio, at weddings, no one questions it anymore. But that wasn’t always the case. Today, we have all kinds of Raï, such as sentimental Raï, vintage Raï, and even the new-wave stuff that’s blowing up on TikTok.”

In his view, young people are revisiting earlier eras with fresh eyes and a newfound sense of pride. “The songs we used to roll our eyes at are the ones we fall in love with later,” he reflects.

“It’s the same with fashion and aesthetics. Nostalgia hits differently as you get older. And that’s why I feel so driven to rethink old Raï sounds. This generation is ready to appreciate it.”

“And honestly, in our culture, artists can last forever,” he adds. “Even if they haven’t dropped an album in years, people still listen. It’s not like in the Western industry where everything’s fast. This music is part of who we are, and that’s never going away.”

Comments (0)