In Egypt, a single sharply-drawn caricature has often spoken more defiantly than a thousand words. As Egyptians overthrew governments, protested injustice, and sought new freedoms, one weapon has remained constant and quietly mighty: the satirical cartoon.

From colonial resistance to digital dissent, caricature has served as a visual battlefield where Egyptians waged their quiet revolutions.

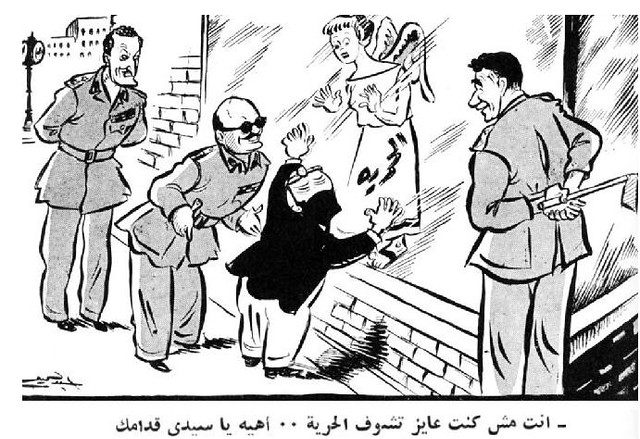

During Egypt’s most turbulent modern moments, such as the anti-colonial protests of the 1919 Revolution and the electrified rallies of Tahrir Square in 2011, caricature amplified the voice of the people against those in power.

Whether sketched on yellowed newsprint or shared with hashtags on Facebook, Egypt’s caricatures have inspired protest, fostered community, and cut through censorship when words grew too dangerous.

Caricature in Egypt has not simply functioned as comic relief, but rather as a fiercely democratic medium, embedding coded resistance within lines and ink. Politically charged artwork often marked the pulse of social unrest, with cartoons reflecting public sentiment and shaping it, fueling debate, encouraging solidarity, and forging new social contracts.

The tradition of political cartoons in Egypt dates back to the late 19th century, coinciding with the rise of the popular press. Early editors and illustrators, often part of the emerging intelligentsia, wielded cartoons as tools of dissent against both colonial and local autocracy.

One notable pioneer, Yaqub Sanua, also known as Abu Naddara, meaning “the man with the glasses,” used satire in 1878 to challenge imperial policies and the corrupt rule of Khedive Ismail and later Khedive Tewfik. His illustrations helped turn public opinion against the rulers, and he continued publishing satirical caricatures from Paris for nearly three uninterrupted decades.

By the time of the 1919 Revolution, Egyptian satirical magazines such as Al-Kashkul (The Notebook) and Al-Lata’if al-Musawwara (Illustrated Witticisms) played a formative role, actively engaging in nationalistic debates and propagandizing social change to end British colonialism and imperialism from 1918 to 1924.

Of the cartoons published in these Egyptian magazines, one hundred and eighty-two humanized political figures, including Saad Zaghloul, portray and interpret events and people, revealing their flaws, strengths, and unique traits, rather than simply documenting them. The satirical pieces lampooned colonizers and transformed sterile records into living memory, making complex political struggles accessible and immediate for the general populace.

The mid-20th century marked the “golden age” of Egyptian caricature. Freedoms briefly flourished after World War II, as Egyptian artists like Bahgat Osman and Mustafa Hussein led a tradition of bold graphic satire, commenting on social and political issues.

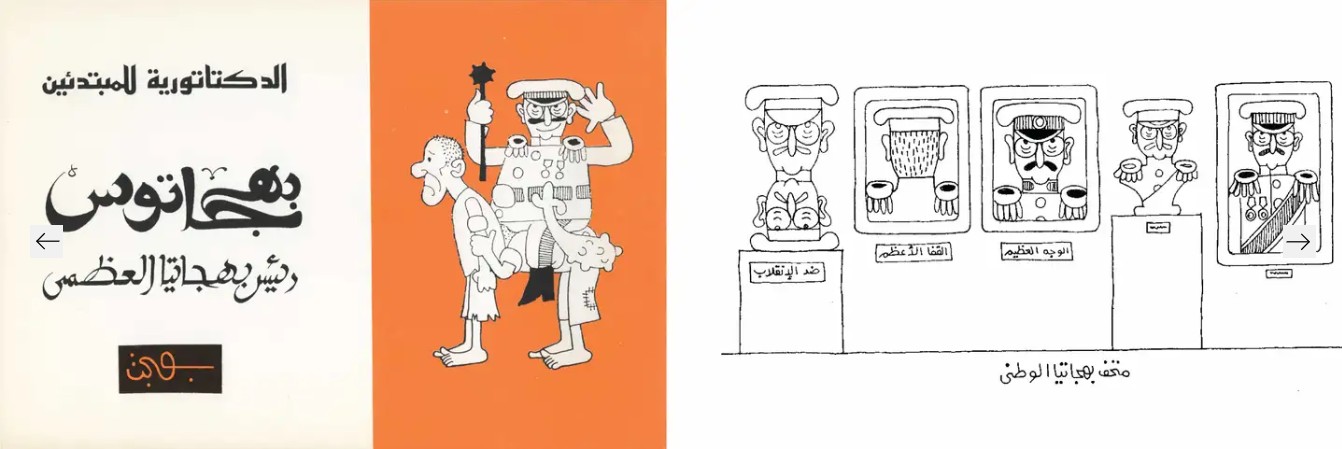

A hallmark of their work was the use of fictional characters to critique the government without directly naming it. One example is “Bahgatos”, a cartoon dictator created by Osman in his 1989 book Al-Diktaturiya lil-Mubtadi’in, which means Dictatorship for Beginners. Set in the imaginary republic of Bahgatiya, the character satirized authoritarian rule, hammering themes like corruption, repression, and poverty through sharp, humorous drawings.

However, this artistic freedom was often precarious.

In the 19th century, rulers such as Muhammad Ali set early precedents for censorship by restricting what presses could publish, and subsequent leaders institutionalized controls through laws like the Censorship Law No. 430 issued under Gamal Abdel Nasser, and expanded during Anwar Sadat’s rule. These regulations, often justified in the name of preserving public order or morality, enabled authorities to suppress content deemed politically sensitive or critical of the state.

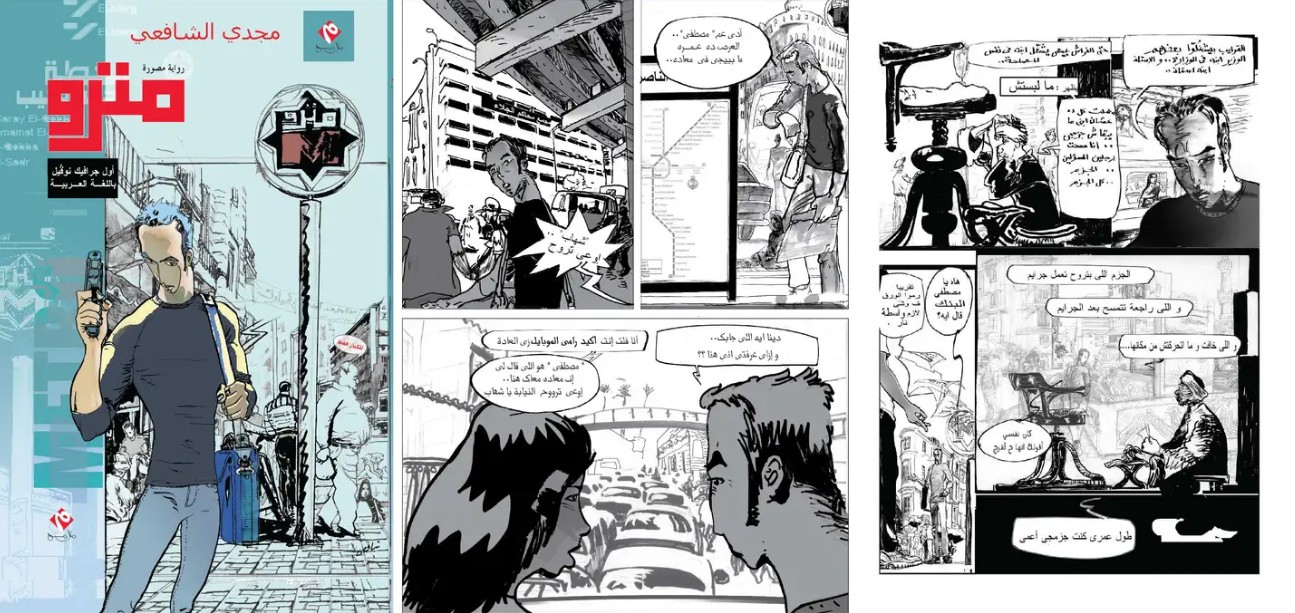

Successive regimes continued to oscillate between tolerating and tightly controlling satirical expression, wary of its ability to stoke unrest. An example of this uneasy relationship between the state and satirical art emerged in 2008 with the release of Metro, a graphic novel by Magdy El Shafee that addressed corruption, poverty, and social injustice in Egypt.

The narrative follows two young men, Shehab and Mustafa, as they navigate their harsh and oppressive daily life. Frustrated by systemic corruption, they turn to crime, plotting a bank heist to steal five million dollars.

The book was swiftly banned by authorities for allegedly “offending public morals,” due to its political commentary and the inclusion of a sexual scene. El Shafee and Malameh publishing house faced legal charges, under Article 178 of Egypt’s Penal Code, which prohibits the publication or distribution of materials deemed offensive to public decency, and were eventually fined 5,000 Egyptian pounds each.

In a 2000 analysis of a contemporary Egyptian caricature column, linguist Bahaa-Eddin M. Mazid noted that even under strict censorship, cartoonists skillfully used symbolism, double meanings, and visual puns to sidestep red lines, often shaping public discourse where direct speech failed. A 2019 academic study by May Samir El-Falaky, a professor at the Arab Academy for Science, Technology & Maritime Transport, further found that Egyptian cartoons during times of political upheaval conveyed powerful socio-economic messages and played a role in shaping national identity.

The digital age would supercharge caricature’s social impact. In the run-up to and during the 18 days of the 2011 Egyptian revolution, satirical cartoons spread through Facebook and Twitter, surpassing the reach of opposition newspapers.

On Tahrir Square, caricature took three defining roles, according to a 2012 study by researcher Eliane Ettmüller. It worked as a direct political weapon challenging Mubarak’s legitimacy, as morale-boosting satire keeping protesters’ spirits high, and as a communicative tool, broadcasting the revolution’s message beyond the square in many languages.

A key theme, as identified in both qualitative studies and real-time surveys of protestors, was that visual satire sharpened collective resolve and democratized dissent. Social media platforms, by multiplying the reach of each cartoon, had turned what was once “underground art” into a public rallying cry.

Today, the boundaries of caricature are being reshaped by shifting political climates. Despite the risks, caricaturists continue to observe and use humor and satire to comment on social and political issues. Their work remains a vanguard for freedom of expression and an enduring mirror for society’s contradictions.

Comments (0)