In a noisy café in downtown Alexandria built in the early 1920s, Mohamed Gohar, a cultural heritage researcher, activist and practicing architect, attentively gazes around the spacious room while sipping on a small cup of sweet Turkish coffee. If you mingle in Alexandria’s cultural circles, you likely know Gohar, and chances are, he knows you as well.

Before we begin our conversation, someone approaches him to express their appreciation for his work in documenting the city’s architecture. “I just wanted to say that I really like what you upload on your page,” a young woman in her twenties says. Letting out a humble smile, Gohar thanks her, and sits back down again at the dark-brown wooden table across from me.

Architecture in Alexandria has been attracting attention in recent years. A spotlight has particularly been directed towards the numerous demolitions of historical buildings that have occurred here. This has paved the way for lucrative housing development schemes led by contractors and investors.

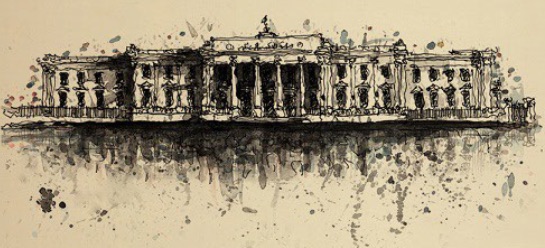

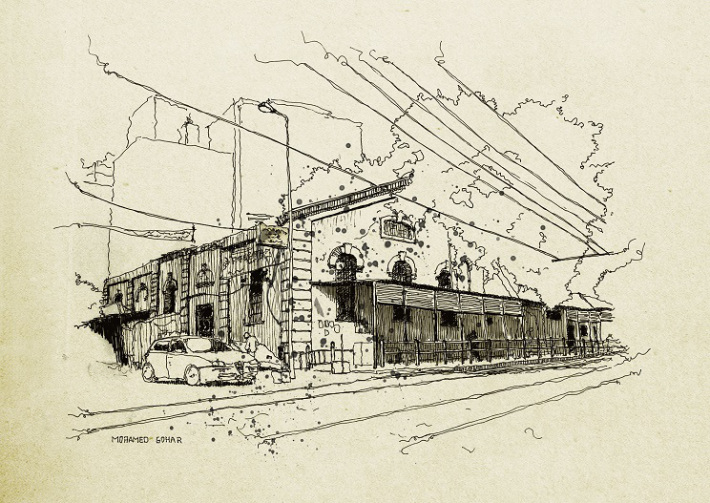

Mohamed Gohar has gained local notoriety for his efforts to document the architectural and cultural legacy of Alexandria through an arguably creative method. By way of sketching – accompanied by written descriptions – he captures snippets of buildings, their history and other aspects of the built environment as a means to safeguard the un-matched value he argues they bear.

“There is a famous quote that says ‘if you have no history you have no future’ which means that architectural heritage is an asset you cannot neglect,” Gohar says, highlighting how the history and culture of cities especially can be utilized to attract tourists.

The 34-year old architect, who currently works at a consultancy firm as a designer, is also the founder of a heritage preservation project called Description of Alexandria. The project aims to document the city of Alexandria through sketching, while also seeking to raise the public’s awareness of threats to the built environment by providing historical descriptions of the buildings that are recorded.

The results are continually published on the project’s website and Facebook page. Gohar is also the founder of a journal with the same name, which so far has been published in five issues.

Having graduated from Alexandria University in 2005, Gohar has more than 13 years of experience working as an architect. During his studies he focued on the historical roots of traditional local architecture and its connection to modern urban society. After graduation, he moved to Dubai where he witnessed the upswing in architectural development that was taking place there at the time.

“There was an architectural boom happening there; it was a dream for every architect to experience. But after one and a half years, I discovered it was not my world, I couldn’t live there because, for me, it was too perfect, it lacked history and layers of culture, so I decided to come back to Alexandria, even if it was not the perfect situation,” Gohar explains.

Disconcerted about the approach Dubai-based architects were following, he says they were trying to construct buildings that aimed to express a well-grounded history and culture, which in reality, he exhorts, were non-existent.

“Besides the modernist movement in architecture, many architects in Dubai were trying to apply traditional Arabic architecture to a modern city without any grounded roots. They just took the essence and the external image of the Arabic traditional architecture […] that had no relation to the people living there.”

Repeatedly stressing the importance of taking into consideration the interaction between buildings and a city’s residents when designing new structures, Gohar points to the lack of vision that characterizes contemporary Alexandrian architecture and urban development.

“We don’t produce any architecture in Alexandria, not at all […] and we don’t have a real vision for the city,” he says, adding “we just build some blocks to contain some people, that’s it, it’s totally functional thinking”. He takes the example of a recently-built bridge on the seaside corniche. When the city administration decided to build it, it didn’t initiate a dialogue with the people inhabiting the area, nor professional architects and planners. “They built it and just thought about the investors,” Gohar says with an apprehensive tone.

The architect first became interested in heritage documentation during his master’s studies. He was doing research in the poor al-Max fishing village located in the western parts of the city. When he finished the research, he went back to the village to show the residents what he had produced; a set of drawings and sketches of the village and improvements that could be made. “That was the very beginning of trying to document what we have without neglecting the old and [instead] starting building from scratch”.

The power vacuum that emerged with the eruption of the 2011 revolt meant that the country’s building codes and regulations could be overlooked; something that was vigorously exploited. “After the revolution, due to the lack of rules and police implementing the rules, people looking for quick investments [could] demolish old buildings and build new ones. The people I’m talking about are mainly contractors working without plans or visions, they are only driven by personal interest,” he explains.

Through his documentation project, Gohar aims to engage both the public and fellow architects alike about the rich cultural and architectural heritage of Alexandria. “When you lose a building you don’t only lose some walls and bricks; you lose their historical content, and that is why I believe we have to fight to keep them alive not because they’re special in themselves, but because of the connection that exists between the city and the people.”

Comments (2)

[…] Read here […]

[…] a noisy café in downtown Alexandria built in the early 1920s, Mohamed Gohar, a cultural heritage researcher, activist and practicing architect, attentively gazes around the […]