Souad, a refugee from Syria and a mother of four, lost her husband on a failed illegal trip to Europe. Authorities never found his body and the family, which had escaped the airstrikes in Latakia in 2012, ended up with the same fate as thousands of others: broken, through the circumstances of war and political instability.

However, Souad’s story was not an obstacle to her career as a certified human development trainer. She resolved to better herself and continue her practice, even while her husband was in Libya, prior to his tragic accident.

Initially, the harsh reality of relocating to Egypt forced her to consider starting her own business. Having witnessed the positive effects of communication and training in Syria, namely through a Neuro-Linguistic Programming (NLP) course, Souad was keen on sharing her training with other refugees and Egyptian disenchanted from the Egyptian revolution.

With time, Souad started giving conferences and talks at numerous universities across the Middle East, inspiring others and taking the stage regularly. Today, she is working on increasing her outreach and empowering other women to follow suit.

Indeed, Souad is not the only refugee to have carved a success story for herself and her family in Egypt.

Refugees like Souad are admitted to Egypt on the basis of humanitarian need; they are integrated within society rapidly with children successfully enrolling in Egyptian schools. They have typical endured years of dislocation and instability, fuelled by disorientation and a lack of knowledge on the countries willing to receive them.

Once arrived and coming to terms with the need to build a life from scratch, however, most refugees develop an entrepreneurial spirit.

Fostering a taste for startups

“Migrants are more likely to become entrepreneurs globally,” says Ayman Ismail, founding director of AUC Venture Lab.

“Any individual immigrating, whether it’s a migrant or refugee, usually is someone who left their life so they have higher risk-taking and perseverance. They are hungry to build something new wherever they’re going so that behaviour and attitude makes them want to push hard,” he explains.

This is furthermore fuelled by a lack of belonging to the local network and the opportunity to consider having a career with the government or within corporate.

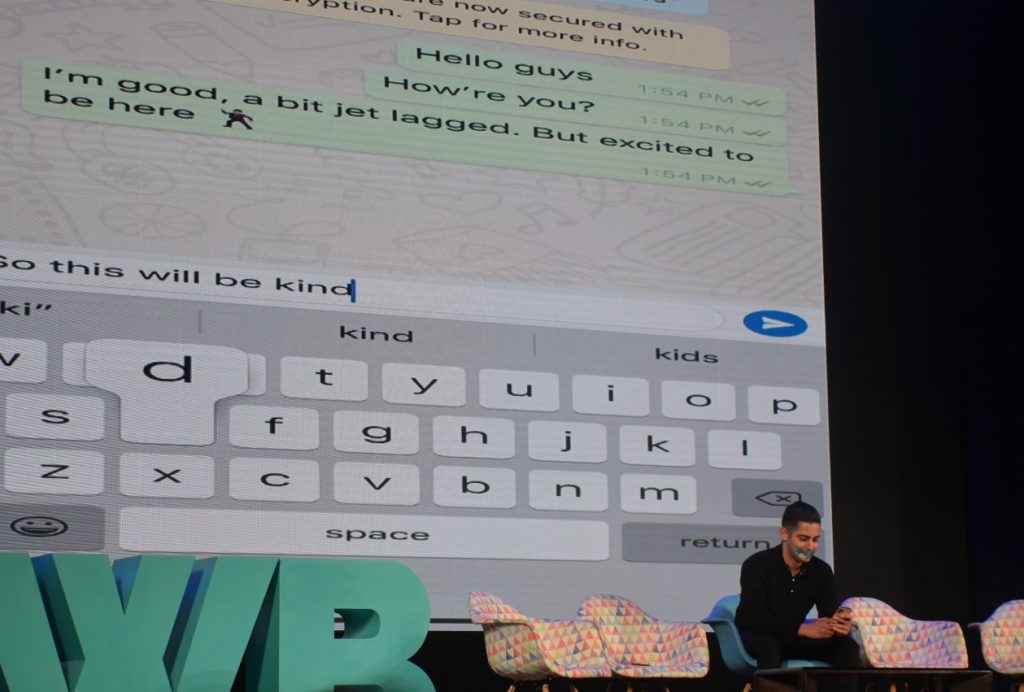

During Startups Without Borders’ summit, Country Director of Startup Grind in Jordan Mohamed Salah and Angel investor Amr Shereen echoed this observation when speaking about university students’ engagement in entrepreneurship in the United Kingdom.

International students more likely to become entrepreneurs and then migrants as opposed to local students as the latter are happy in their comfort zones.

“International students who become immigrants are a key when it comes to economic development that’s why universities are trying to increase the number of international students,” explains Salah about the global trend.

Refugee entrepreneurship: success stories

Dedicated to helping refugee entrepreneurship grow, Startups Without Borders (SWB) links migrant entrepreneurs with the resources to establish their business and startup.

The ambitious platform, founded by Valentina Primo, also provides investors with an entry-point to new or small-scale startups with innovative potential.

In November 8 and 9, it launched its annual summit where it gathered pioneers, startup founders, international speakers to expose the Egyptian startup scene and the successful practices of entrepreneurship at large.

One of its key features, through the exposure of refugee’s success stories, was to inspire and give entrepreneurs concrete tools to transform their ideas into businesses.

Among the migrant refugees present was Reem Sabouni, a founder of Mom’s Club aimed at supporting single mothers. Her business has expanded to countries such as Algeria, the United Emirates, Syria and soon, Sweden.

As for Refaa Al Refai and Souad Mohamed, they’ve been working in training and human resource development.

“Egypt is the space any businessman needs,” says Al Refai at the summit. “ I wouldn’t have been able to do what I did in Egypt in other places.”

Al Refai’s center ‘Soryana’ aims to reduce gaps between indifferent communities and cultures, as well as fostering integration efforts through multi-ethnic workshops.

Her center has helped 16,500 refugees of a multitude of nationalities. in over 15 governorates across Egypt.

Similarly, Souad expressed that her entrepreneurship spirit and appreciation of work were refined in the host country.

“I learned the importance of women in the culture of work here [in Egypt],” she says.

“The original statue of liberty of the United States of America was inspired by the Egyptian falaha [female farmer]”.

Primo believes that the migrant entrepreneurs often lack the network in the countries they relocate to, since they haven’t been sufficiently exposed. This is also taking into consideration that the startup scene in their countries of origins were usually in its early days as they were leaving.

As such, despite certain setbacks, such a proper understanding of legalities to start a business in the Middle East’s most populous country, migrants are usually capable of launching their projects.

What does a migrant/refugee’s participation mean for the economy?

At the 2019 Munich Security Conference, Egyptian President Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi stated that Egypt hosts approximately five million refugees who also receive governmental healthcare and work licenses.

Despite Egypt’s slow, recovering economy, Syrians in particular have a reputation for being industrious and work-driven.

From providing a steady stream of Levantine mezzes, shawarmas and, surprisingly, Indian cuisine, to fashion retailing in Cairo, their businesses have proven to be particularly lucrative and popular.

Most have resettled in areas now famous to house Syrians and other migrants, such as ‘Little Damascus’ in 6th of October, Maadi, Rehab and Mohandessein.

A 2017 report by UNDP, World Food Programme (WFP) and the International Labour Organization (ILO) illustrated that Syrian refugees have contributed $800 million in investment to Egypt’s economy.

Moreover, according to SWB, Syrian entrepreneurs have set up 2,000 factories, employing a large number of citizens, since the war began.

Ismail credits this success to Egypt’s large informal sector and its capacity to absorb newcomers.

“Egypt has a huge population and it’s already acknowledging that Syrians are amazing with food and textiles,” enthuses Primo who believes that the Egyptian market readily welcomes migrants into the workforce.

“You create GDP for the country, economic growth, jobs and you’re innovating. You’re bringing in something new and you’re solving a problem,” she says regarding the importance of including migrants and refugees into the workforce worldwide.

Nonetheless, the engagement of refugees in Egypt’s entrepreneurship scene remains limited due to legal instability and limited funds.

“Being an entrepreneur is a privilege, you cannot become a tech entrepreneur if you cannot feed your family,” says Ismail, who believes that refugees are more likely to innovate and get take their first steps into entrepreneurship once they feel secure.

“Most of the time, I see them [migrants] in small and medium enterprises rather than tech. The reason is they’re not usually settled yet; they don’t have a lot of capital or a network, so the main objective is to get into business to generate cash quickly and work hard, more than long-term, high-risk investment,” he explains to Egyptian Streets.

The path to getting started: steps in Egypt

To be able to fully engage in entrepreneurship in Egypt, this requires a strategic approach which makes this choice viable for those who are resettled across Egypt.

Souad believes that migrants and refugees need to develop their skills, partake in courses, and strengthen their drive to succeed.

For Primo, the steps are more defined.

“Gather a team, try to access an incubator, and start serving your customers. Listen to what is needed, take their feedback, keep iterating your product until you find there is traction,” she recommends while also stressing the importance of partnerships and networking.

It is to migrants, and the host country’s, advantage, that initiatives such as Startups Without Borders exist as the platform helps connects pioneering entrepreneurs with local and international expertise to launch their ideas.

One thing is clear: refugee’s entrepreneurial enthusiasm and motivation are the optimal tools for starting out. While this would entail a bumpy start and needed patience, it’s an investment that tends to yield economic returns and innovation.

Featured image DFID – UK Department for International Development.

Comments (0)