Two tributaries of the world’s longest river, one intimate struggle in the making for centuries: the Renaissance Dam. Sitting near-completion and only partially full, the Ethiopian structure has been deemed an aggressive – if not viscerally dangerous – encroachment upon the Blue Nile’s basin.

As things stand, Egypt dines with speculation, its media outlets saturated with justifiable anxieties and not-so-justifiable fear-mongering. While the world looks on, eyes fixed on the spectacle that is the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), Egypt and Sudan grapple with this newfound life-source tourniquet.

So, what brought on this cutthroat antagonism?

A simple answer: water.

A not so simple answer: decades upon decades of slow-burning tension over the Nile river.

Between British imperialism and the looming paranoia of drought, there is plenty worth unpacking but few willing to do so. Rather, for the past decade, people have been quick to cut their teeth on the subject with heart and little context. Egypt and Ethiopia’s lack of rapport can be credited to century-old claims, now dampened and delegated to the margins of thought in favor of more recent developments – as is the case with most multifaceted, fury-inducing issues.

Given that most sources are muddied with peripheral observations and straw-man arguments, let’s break down the milestones of Egypt and Ethiopia’s long-reigning conflict with a bite-sized timeline.

It’s 1898 and Britain has complete control over Egypt, Sudan, and most of the Upper Nile. Between referring to Egypt as “the gift of the Nile” (per political scholar Haggai Erlich in: The Cross and the River: Ethiopia Egypt and the Nile) and their desire to make the most of the massive river’s resources, Britain’s keen attitude towards developing Egypt as a profitable colony puts Egypt at an advantage regarding its water usage and control.

1929: Britain grants Egypt, in a post-imperialist treaty, the authority to veto “any project involving the Nile by upstream power.” Despite involving more than one upstream state, this agreement excluded Ethiopia at the time of signing, and is the cornerstone of future contention. Much of current Egyptian argumentation stems from here, too; professor and scholar Nader Nour El-Din argues that since Egypt was “founded, and continues to depend, on the particular water allotted to it” this would threaten the foundation of its economy and actively growing population.

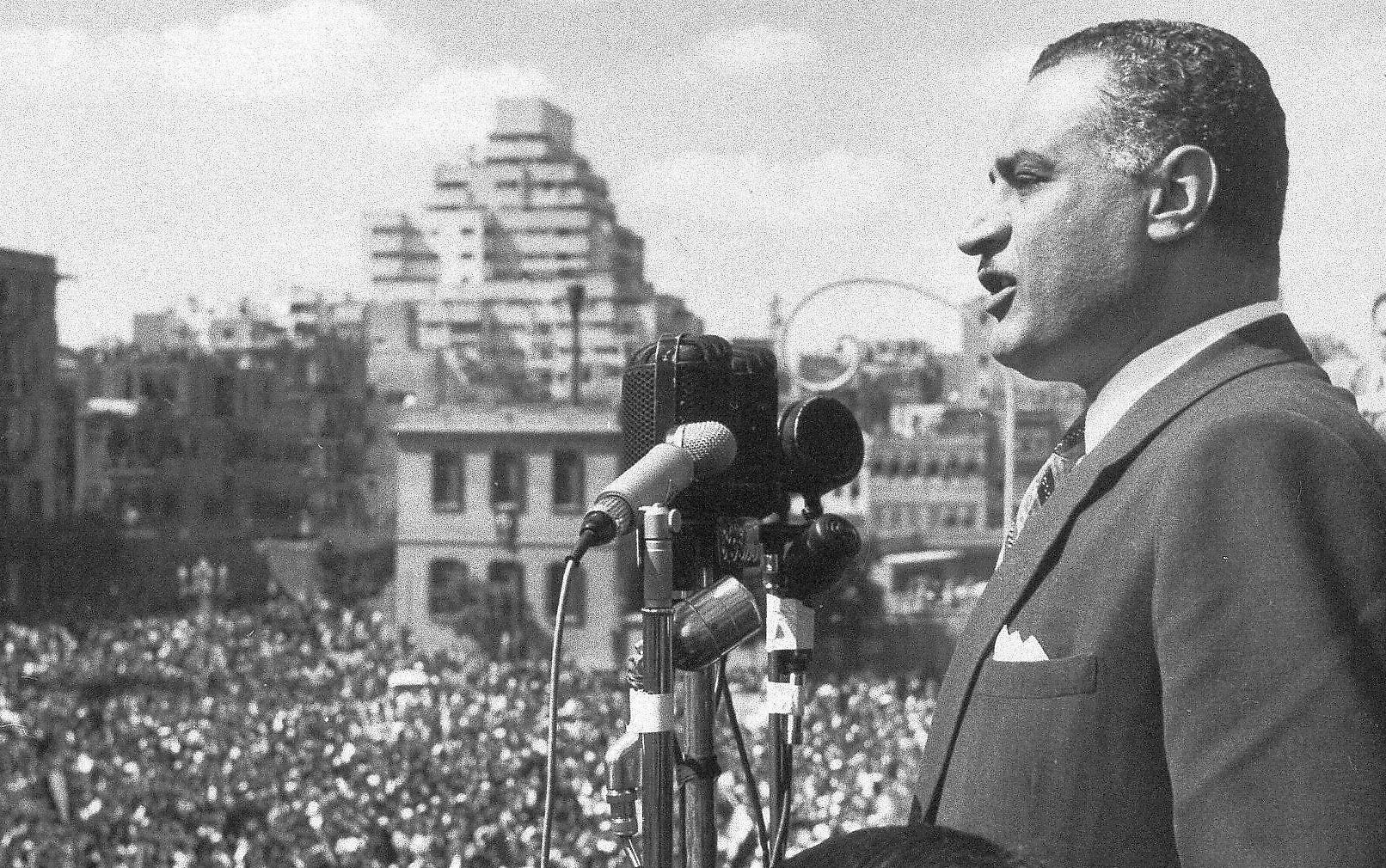

1960: The age of nationalism and revolutionary Arabism brings Gamal Abdel Nasser to the reins of power – and with it, a sundry of issues with Ethiopia when he sets into motion the world’s largest embankment dam: the Aswan High Dam. Around this time, Nasser actively dismisses any and all notions that Ethiopia is the sole source of Nile water. With Ethiopia on the brink of civil war, the issue of water rights and shortages is put on temporary hiatus.

1987-1988: Dismissal of Ethiopia’s importance provides Egypt with a cautionary tale. When Ethiopia is hit with a drought that threatens both Nasser Lake and Egypt’s water provisions, it becomes impossible to ignore Ethiopia’s vitality as the heart of the Nile. The vulnerability of losing its water supply had Egypt reconsidering ways in which to secure itself for decades after, spawning the very fear still present today. Many believe that the Aswan Dam was “the wrong dam, in the wrong place” (per political scholar Haggai Erlich) and an opportunity to negotiate a better location, strategy, and treaty was missed by the Nasser cabinet.

1993 sees the Framework for General Co-operation between the Arab Republic of Egypt and Ethiopia, a treaty determined to “consolidate ties of friendship” by securing their respective resources and agreeing to abide by international law and commitment to the United Nations.

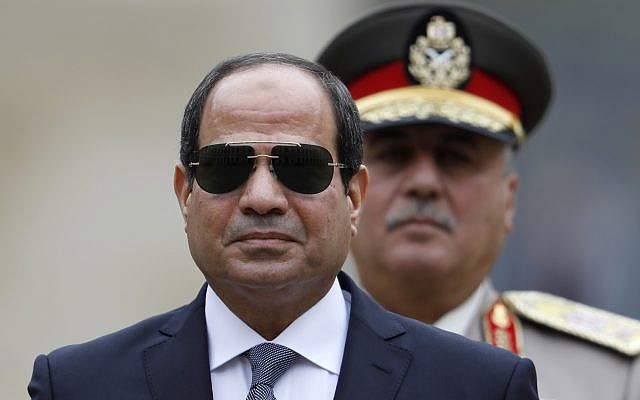

2011: Egypt goes through political upheaval and social unrest, until transient president Adly Mansour takes charge. Parallel to these events, Ethiopia sets in motion construction for the Renaissance dam before agreements with Egypt are reached (i.e. water supply percentages, reservoir filling schedule). Ethiopian prime minister Meles Zenawi claims that the dam is for the purposes of power (i.e. conducting electricity) and that Ethiopia will, in no way, benefit from the GERD for additional water provisions.. Zenawi holds that Ethiopia’s actions are in line with the 1993 Framework. Ethiopia later recants Zenawi’s assertions, arguing its right to a percentage of the water supply filtering through the dam.

2013: Egyptian officials prove hostile under president Mohamed Morsi when an audio-clip is released to the public, suggesting militant approaches to preventing Ethiopia building a dam across the Blue Nile (one of two central tributaries of the Nile). This marks the beginning of Egypt’s and Ethiopia’s outwardly strained relations. Ethiopia refuses to make any claims regarding potential collateral in Egypt and Sudan or impact on water supply as construction begins. Their refusal to give numbers stretches on into 2021, a decade later.

2015: Egypt, Sudan, and Ethiopia embrace the Declaration of Principles, which stipulates that downstream countries should not face adverse effects as the dam is built.

2020: Ethiopia announces its intention to begin filling the massive dam’s reservoir, shutting Sudan off from three of four water diversion outlets in the process. Despite holding several tripartite talks between the three involved parties (represented by their respective water ministers), no halfway point was reached.

And now, 2021:

With tensions escalating, Egypt reaches out to the global community, heading an Arab League meeting regarding the issue. In a letter to the United Nations Security Council (UNSC), Addis Ababa objects to the “unwelcome meddling” of the Arab League in primarily African matters, asserting that the issue “does not fall within its purview.” In response, the Arab League condemns these claims, denouncing them as attempts to “portray the issue as an Arab-African conflict” (per: official source at the General Secretariat).

Cairo produces its own letter to the UNSC, and in it, posits that technical matters were never the source behind disagreement – rather, it is Ethiopia’s pattern of unilateralism. Going further, the letter condemns Addis Ababa for its “substantively intransigent positions, [its] procedurally unconstructive attitude” and the “intent on imposing a fait accompli on Egypt and Sudan.”

Ethiopia announces that the second filling of the dam is complete. A United Nations Security Council meeting leads to little save further delay of decisive negotiations. It is decided that Cairo, Addis Ababa, and Khartoum are encouraged to reach mutually beneficial agreements without the Council.

It stands to reason that, when all is said and done, there is still much uncertainty regarding such a topic. The waters between Egypt and Ethiopia are turbulent, despite both states having emphasized an ardent need for agreement. Egypt maintains that it is not opposed to the Renaissance Dam as a project, but rather is concerned with the outcomes. Ethiopia’s silence on the matter of numbers, water supply, and management continues to pose an issue of security.

Thus far, no trilateral agreements have been reached between the Nile-bound states, and upon the dam’s completion, Ethiopia will have complete sovereignty over the Blue Nile gorge.

While this conflict was predicted as early as the 1980s, and has been fermenting since the start of the 20th century, it remains a risky, volatile conversation. Between Egypt’s full dependence on the Nile and Ethiopia’s laborious efforts to secure water, the sensitivity of the issue becomes increasingly apparent and harder to ignore as time lapses.

Subscribe to the Egyptian Streets’ weekly newsletter! Catch up on the latest news, arts & culture headlines, exclusive features, and more stories that matter delivered straight to your inbox by clicking here

Comments (12)

[…] A History of Turbulent Waters: Egypt, Ethiopia and the River Nile […]

[…] المصدر by [author_name] كما تَجْدَرُ الأشارة بأن الموضوع الأصلي قد […]