“On November 15, 1920, an elderly man living in the al-Labban district of Alexandria, Egypt, reported a shocking discovery to his local police station. While installing a new sewage system in an apartment building managed by his family, he dug up the skeleton of a woman,” writes Nefertiti Taklan, an Assistant Professor of Modern Middle Eastern History at Manhattan University, in her Ph.D. dissertation to the University of California.

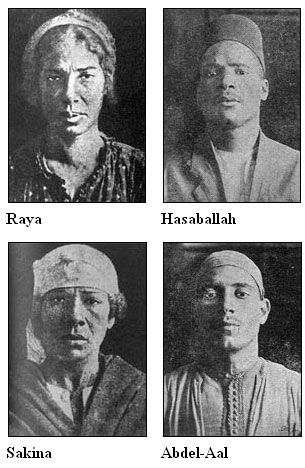

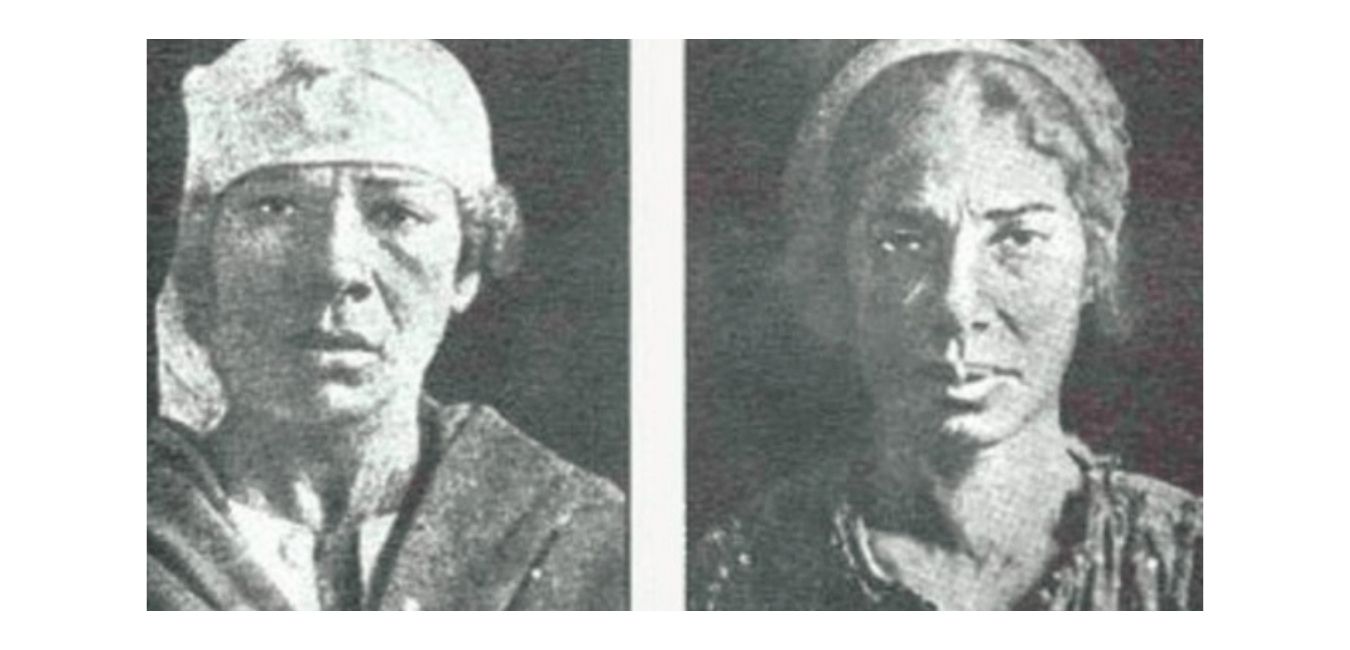

The discovery was connected with two of the most infamous characters of Egyptian popular culture: Rayya and Sakina. Both were the first women to receive the death penalty under the modern Egyptian judicial system.

Theirs is a story of a series of homicides that caused communal panic in Alexandria in the early 20th century under British colonial rule. The murder case started in 1919 and ended in 1921, with a total of 17 bodies of women and men buried underneath Rayya and Sakina’s house.

According to Taklan, the case of Rayya and Sakina is much deeper than a grisly serial killing crime. Primary sources such as handwritten legal reports and investigations in Dar al-Mahfuzat and the Bibliotheca Alexandrina suggest that the two women were used as scapegoats, to target clandestine sex work in Alexandria. The case was widely molded into a story of infidelity and moral bankruptcy when, in reality, it was a series of homicides carried out by a gang of six members for money.

The infamous sisters are frequently portrayed in a comedic frame in popular culture and are the immediate go-to reference for female serial killers in Egypt. Surrounded by a group of accomplices which included their spouses and two other men, Rayya and Sakina certainly did not act alone – why, then, are they always depicted as the main characters?

The Truth Behind the Tales

The story begins with the move of Rayya and Sakina, and their respective husbands from Upper Egypt to Alexandria in search of a better quality of life. Taklan argues that during the 19th and 20th centuries, as a result of the Egyptian economy’s crash due to World War I, the informal economy emerged, allowing Egypt’s poor to earn money through unconventional jobs.

It was this economic crash that also led Rayya and Sakina’s spouses to lose their cotton industry jobs. Accordingly, the two couples ran a brothel business that hosted a myriad of people from various social backgrounds. Each one of the four individuals had their role in running the brothel and recruiting prostitutes and male customers. And, as their financial situation worsened, they became increasingly reliant on the income it generated.

Their first brothel was established near the British army base, attracting a large clientele of British soldiers along with local businessmen and married men. Both couples, Hasaballah and Rayya, Abdel’al and Sakina, eventually opened more than one brothel in different parts of Alexandria to meet the demand of the rising number of patrons. Yet, prostitution was illegal, a fact which prompted the sisters to consistently deny providing such services.

With the end of World War I and the outbreak of the 1919 revolution in Egypt, the economy’s deterioration persisted, and so did Rayya and Sakina’s business. Realizing the precocious position of their recently accumulated wealth, the gang’s homicidal tendencies began to surge.

The gang’s crimes had a consistent pattern: Rayya and Sakina would befriend and lure wealthy women at the market into their house in the Labban neighborhood, offering them alcohol until they became intoxicated. Subsequently, their spouses, Hasaballah and Abdel A’al would strangle the victims, take their jewellery, and bury their bodies underneath the house.

At the time, wealthy women in Egypt did not place their money in banks, preferring to solidify their wealth in the form of gold jewellery. The flamboyant and eye-catching jewellery would render the victims easy targets for the gang.

Despite a precedent case in Tanta, where a man named Mahmud Allam committed a series of murders on exclusively female victims, the case of Rayya and Sakina gained more attention as media coverage focused on the fact that the perpetrators were women, linking Rayya and Sakina’s misdeeds to ‘public immorality’ in society, casting the women, and their crimes, through a specific lens

Reports on Rayya and Sakina in newspapers delved into the victims’ profile and their sexual activity, or on Rayya and Sakina themselves, thus neglecting Hasaballah, Abdel A’al, and two other men’s contributions to these crimes.

According to Elena Chiti, professor of Middle Eastern and Turkish Studies at Stockholm University, newspapers focused on shunning the sexual activities of women who were frequent to the brothel by calling them ‘immoral’ and called different areas of Egypt to protect Egyptians from ‘satanic desires’.

Therefore, this tone used in reporting focused on brothel business and the role of Rayya and Sakina in managing it rather than the gang’s homicides, using Rayya and Sakina as the front despite them being only two members of the six-member gang.

Chiti’s paper ‘Building A National Case in Interwar Egypt: Raya and Sakina’s Crimes Through the Pages of Al-Ahram (Fall 1920)’ highlights that despite the gang’s arrest, newspapers mainly used Rayya and Sakina as the main perpetrators and referred to their spouses as “Rayya’s husband” and “Sakina’s husband” rather than their names. She deduces that newspapers took advantage of the fact that they were women, branded them as immoral, and accused them of public indecency to “captivate the public.”

Theirs is a story where economic hardship and the socio-political reality of Egypt of the period intersect. Yet, while Rayya and Sakina were inaccurately portrayed as the only perpetrators in one of Egypt’s most high-profile serial killings, they were ultimately still complicit murderers. What is worth nonetheless revisiting is the lens by which they are remembered, while removing gender bias from the case. Taklan suggests that it would be more accurate to refer to their crimes simply as the ‘1921 murder cases’ rather than the case of ‘Rayya and Sakina’.

Over the years, the gruesome, complex story of the murders continued to captivate mass audiences and imagination, culminating in the story embodiment in film (1953, 1955, and 1983), a 2005 TV series featuring Egyptian actresses Abla Kamel and Somaya El Khashab, and theatrical productions.

Comments (2)

[…] الأمثلة المبكرة لأفلام الجريمة ريا وسكينة (ريا وسكينة ، 1953). ما يميز هذا الفيلم أنه متجذر في […]

[…] examples of crime films include Rayā wa Sakīna (Raya and Sakina, 1953). What is distinctive about this film is that it is rooted in local culture […]