“We were told not to look beyond the wall and the Libyan Auxiliary Police made the rocky hills shake while they searched for us.”

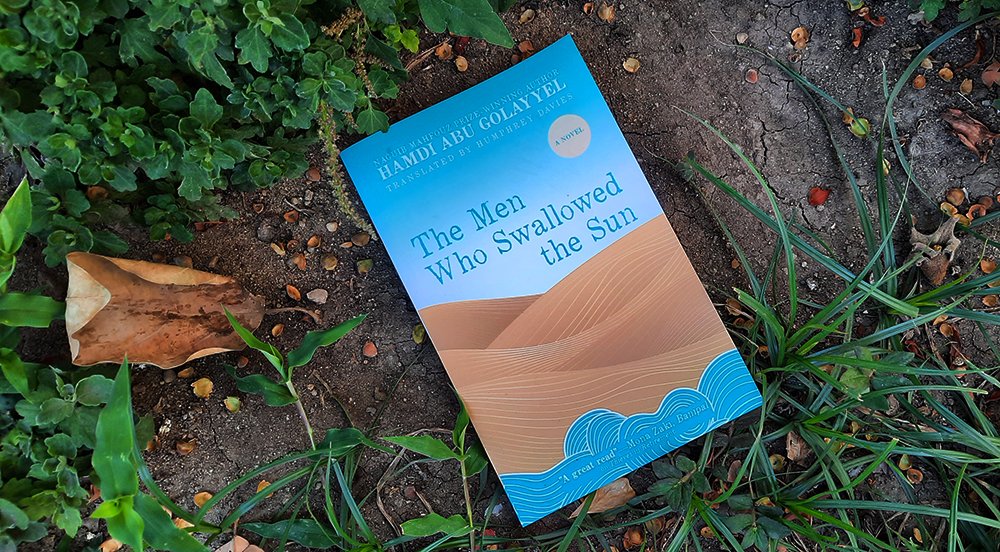

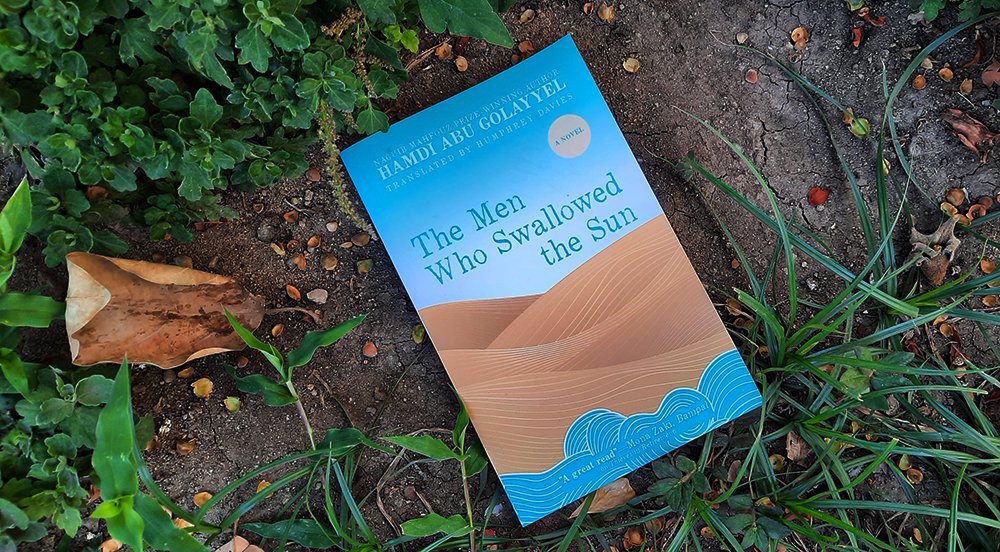

It is a raw, concise vision of an otherwise unsentimental reality. Hamdi Abu Golayyel’s ‘The Men Who Swallowed the Sun’ (2022) spins a furious, unapologetic tale of illegal immigration, discrimination, and erasure. Here is a book that not only attempts to understand the calculus of poverty and aspiration, but also the flawed politics that undercurrent North Africa.

The story follows two Egyptian Bedouins who pry open the jaws of poverty and struggle to climb out. Both do so by making their way to Libya—where they are welcomed and harassed in equal measure, called “pissy little Egyptians” and “Gypos”, but still somehow kept safe by the rebellious, potty-mouthed locals of the Suq al-Khamis district in Libya.

Hamdi, an avowedly autobiographical protagonist and narrator, is unable to make it past Sabha, Libya. He labors at a factory, wasting away between swings of moonshine and pulls of hashish. His parallel, a striking antihero who goes by many titles, namely the Phantom Raider for his reprehensible, “devilish” charm, manages to cross the sea to Italy where he battles authority, makes enemies, and dupes every system handed down to him.

Described as a “bird-snatching leopard […] with a fiercely focused face and eyes that were frank and trusting, even when he was lying,” the Phantom Raider is presented as the reckless youthfulness of luck-seeking Arabs: those who act first, only to be confronted by consequence. Hamdi is his reasonable, if not cynical and unsuccessful, antithesis. While both migrate illegally, Hamdi is led by caution; he stays “in storage” (in hiding) for months on end, at several different locations, seemingly unable to take adequate risks despite his mother’s wishes to “go abroad, son!”

Hamdi leads the reader through ethical dilemmas by the fistful, priming the narrative with his own deeply-flawed estimations. His tangents are many—some about the intricacies of life in the Western Desert, others about his exported sense of self when he arrives in Libya, most punctuated with wit and dark, pitchfork irony. He leaves no room for conversation in this tale, and instead, tells the reader all that they need to know dryly. The dialogue is embedded into the tale, as though told in hindsight; a story recited to a friend, rather than written into a book.

There are no invitations into the setting, no easing into the fray; Hamdi is speaking at you, not to you.

Golayyel is keen on adopting the structure of the Arab epic with a stream of consciousness narrative that facilitates the intersection of reality and fiction. Most times, the reader is unsure if Hamdi is a figment of Golayyel’s creation, Golayyel himself by extension, or whether the narration has switched to the crude Phantom Raider altogether

Regional Politics

From Gaddafi’s Saad-Shiin, who embrace Egyptian Bedouin as fellow Libyans and tribesmen, to critique of Sadat’s politics as a “bitter harvest [of] debauchery” it seems that Hamdi’s grasp on politics is largely inspired by that of Golayyel himself, who grew up as a Bedouin in al-Fayoum.

He goes on to explain the strained relationship between the government and the Bedouin, the ‘Othering’ that occurs within one’s own country. This, he maintains, is what led to Gaddafi’s ability to seduce Egyptian Bedouins into leaving home for a questionable living elsewhere. Profound promises founded only on the tenuous attachment these men had to their homeland. “The word ‘government’ meant simply the brutal power of the police, who could arrest [someone] for no reason other than that he existed.”

Golayyel’s understanding of tribal living, being caught between the unforgiving tides of Egypt and Libya, paint more than a picture of desperation; they provide visceral insight into the experience of being in this limbo.

A man, hiding underneath the floorboards of a Sabha farmhouse; strangers who cannot speak the language of the country they find themselves in; Arab companionship and betrayal on foreign soil. It is a fractured, but undoubtedly compelling set of images that Golayyel delivers with sophisticated storytelling.

Experiences of a Renegade

“The wave would roar and raise the boat till we felt like it was flying and then bring it crashing down into the bowels of the sea […]. There is no God but God, some praying, some saying, I swear I’m going to piss myself, which they did. Everyone thought they were going to die. I sat there and didn’t do anything. I just sat there where I was and waited for death.”

This excerpt sits between the Phantom Raider and his newfound life in Italy. It is an unkind, cutting image of what it feels like to traverse the sea on an inflatable Zodiac, unsure of whether or not the next moment will see survival or suffering. This is one of many points in ‘The Men Who Swallowed the Sun’ that help Golayyel paint a devastating image of illegal immigration.

There are several scenes of Hamdi and the Phantom Raider running for their freedoms—through forests, into animal manure and sheep pens, reliant only on the kindness of strangers who could very well betray them at a moment’s notice. The gritty nature of the book leaves every possibility open, even tragedy, and Golayyel remains unwavering in his depiction of the horrors of poverty and near-death.

He describes how they had “nothing but the shirts on their back” in Egypt, only to be strip searched and objectified in Italy upon arrival, and heinously treated in Libya.

“I could have gone back,” muses Hamdi. “Egypt was far better. Even our own field, if well farmed, would have been better. But it never crossed my mind to go back.”

Dialogues of Race and Sexism

While Golayyel presents a compelling narrative when it comes to the less-than-romantic images of illegal immigration, the faults of ‘The Men Who Swallowed the Sun’ are many. Between stylistic choices of the writing itself, which at times becomes difficult to follow, to strange and uncomfortable descriptions of fellow Africans. It is hard to differentiate between Golayyel and his characters when it comes to opinion, given the choice to have Hamdi inherit his background. This makes it more and more problematic when observing the flippant comments made by Hamdi or the Phandom Raider with regards to race and sexism.

Golayyel makes it a point to emphasize the “blackness” of characters, the size of their genitalia, going as far to say a “bossy Sudanese […] lorded over us. Especially Egyptians, like he was a Libyan when he was a filthy servant.”

This is not the only time wherein Golayyel’s characters make ill-suited remarks about Africans. At one point, a character describes the complacency and “saggy breasts” of an allegedly unattractive African refugee. This comment, in passing, could be forgiven if not for the Phantom Raider’s asides on how “cute” blonde Italian women were, which provide a stark difference in descriptive diction.

Race is not the only issue found with ‘The Men Who Swallowed the Sun’, either. The Phantom Raider is shown as an individual of little ethicality, and yet he is absolved of nearly every sin. He flashes women entirely naked, but it’s a result of his “shy love;” he rapes a woman in the fields, but it is “not real rape” given she was married into a different hamlet.

This issue of race and absolvance comes alongside banal judgements on women’s appearance and on their behaviors. Italian women are criticized for their promiscuity, while Bedouin women are mocked for their modesty. The niqab, for one, is described as “launching its assault in the nineties” turning women into “black forests.” Golayyel also makes it a point to assign Bedouin women as “ours” or “theirs” —which, whether intentional or not, serves to objectify them.

Golayyel’s attempt at a formidable female character comes in the form of Hamdi’s mother. “[My mother] needed a man and I was there, so she decided I was one,” explains Hamdi. “From the moment my father died when I was five she treated me as though I was her husband. Sex excepted, we conducted our daily life as though she was the strong, sensible wife and I the honest, obedient husband.”

Verdict

It seems that, while ‘The Men Who Swallowed the Sun’ provides biting, continuously impactful insight into the life of poverty-stricken Egyptian luck-seekers, it does no favors for any perceived Other. While Hamdi and the Phantom Raider are afforded the grace of narrative forgiveness, the casual bouts of sexism and racism delivered by both of them seems to ruin the sympathetic facade almost entirely.

It’s unclear whether Golayyel purposely adds this layer of bigotry to showcase the reprehensible nature of his characters, or whether it is just an oversight. Both possibilities have their own supporting arguments. Still, it becomes clear that a critical eye is necessary when reading, regardless of intent.

It is essential then, to read ‘The Men Who Swallowed the Sun’ with an open mind. While it offers some key judgments into the life of Egyptian Bedouins and their struggle to survive, it also showcases a more ignorant and unfiltered view—an Othering that happens to these Bedouins by governments, and by these Bedouins to strangers.

The opinions and ideas expressed in this article are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the views of Egyptian Streets’ editorial team. To submit an opinion article, please email [email protected].

Comments (0)