While the debate on the existence of a side-chamber in Tutankhamun’s tomb has been a hot topic in national and international news in recent months, few people realize that British artist Adam Lowe has created an exact facsimile of the young pharaoh’s burial chamber in the grounds of Howard Carter’s house on the West Bank in Luxor. Having visited the original many times, the precision of the replica is slightly unnerving. But perhaps more important than the discoveries made during the scanning of the original tomb are the aesthetic issues surrounding the reconstruction which are shifting our general perception of art history.

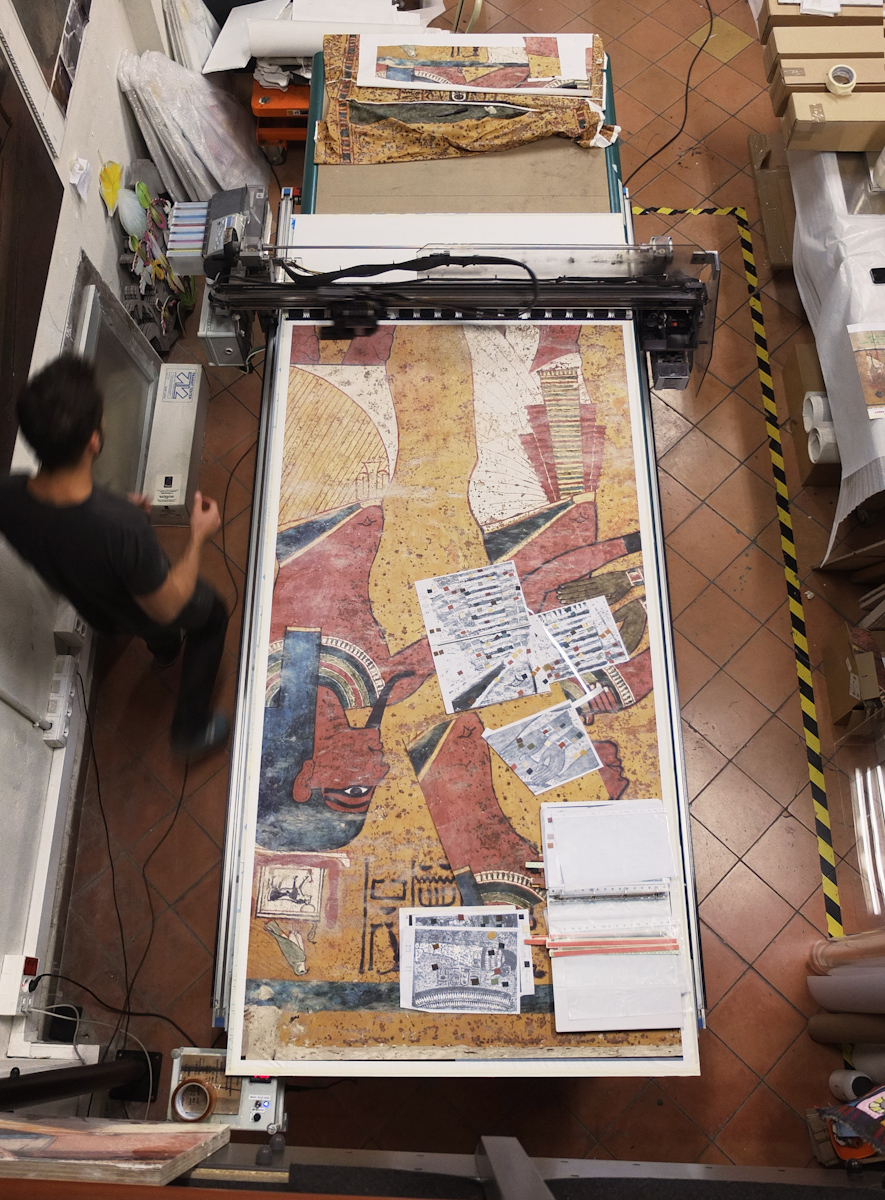

Adam Lowe is what is called a “copyist” and he has produced reproductions of some of the greatest masterpieces in the world. Lowe founded Factum Arte in 2000 with Spanish artist and engineer Manuel Franquelo. Its aim, Lowe told Egyptian Streets, is to bridge the “gap between new technologies and traditional crafts – it’s all about mediation and transformation.” Factum Arte has developed its own 3D scanners and printers, which Lowe says “allow us to to see the surface as the eye sees it, but also some of what lies beneath.” Only the Rijskmuseum in Amsterdam has equipment capable of revealing a similar degree of detail. It is this cutting-edge technology that has allowed one of his core projects – the replica of Tutankhamun’s burial chamber – to be opened to the public in April 2014 and since donated to the Egyptian government.

It is the results of Factum Arte’s original scans for the construction of the facsimile that revealed that one wall in the tomb was painted using a different technique from others as well as the vague outline of a doorway or opening. Drawing on these results, British Egyptologist Nicholas Reeves published an academic paper in which he claimed that Tutankhamun’s tomb usurped part of what was originally the burial place of Queen Nefertiti. The day after it ran, Factum Arte’s website had nearly two million hits. Reeves’ core argument was that the floor plan of the tomb shared no similarities with anything else in the Valley of the Kings. He drew further evidence to support his argument in the fact that much of the treasure found in Tutankhamun’s tomb originally carried the Queen’s name.

The hype surrounding the potential hidden chamber was only amplified by another radar scan performed by the Japanese specialist Hirokatsu Watanabe. His findings seemingly supported those of Reeves and the original Factum Arte scans. But Watanabe’s refusal to share his results has led to much skepticism as to the validity of his claims. He has been quoted as telling the National Geographic website that after nearly four decades in the field his equipment is so fine-tuned that only he can read the results. “I trust my data completely,” he said. “When someone says that they want to check the data, I am so sad.”

More recently, new advanced ground penetrating scans carried out by National Geographic seem to contradict these earlier theories. Dean Goodman, a geophysicist at GPR-Slice Software who analyzed the data from these scans, has been quoted saying that “if we had a void, we should have a strong reflection” but that in reality “it just doesn’t exist.” National Geographic claim to have sent the report to the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities.

A conference on Tutankhamun at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo earlier this month was supposed to shed some light on the debate. The National Geographic team were not, however, allowed to present their findings, leaving the limelight for Reeves and Watanabe to present their research in full. Egyptologist Zawi Hawass, Egypt’s former Minister for Antiquities Affairs, who has been outspoken for quite some time on the potential discovery, went so far as to criticize the debate at the conference. Speaking to National Geographic, Hawass said, “If there is masonry or [a] partition wall, the radar signal should show an image’ but that ‘we don’t have this, which means there is nothing there.” The Ministry however, has yet to provide a conclusive statement on the validity of their original claims.

Whether a new chamber is discovered behind the wall of Tutankhamun’s tomb or not, the controversy surrounding Reeves’ theory has been good for Lowe’s project. Firstly, he has been thrilled with the amount of attention afforded to his work as a consequence of it. Secondly, the potential discovery of the side-chamber was not the purpose of his work but a by-product of it.

“What we are doing is a form of archaeology” with the principal aim of conservation, he told Egyptian Streets, adding, “This and other things we are doing will overturn many accepted opinions and theories in art history.”

And he has a point: The tomb of Seti I is already so damaged by years of tourists’ visits that it is now closed to the general public and can only be seen by paying a USD 10,000 admittance fee. Are we really going to wait until the rest of the Valley of the Kings follows suit?

Lowe says the “critical thing now is to document. Later we can decide what to do with the material we collect. But if we lose the data these things contain then we lose something that could influence future generations.”

It is this obsession with perfect preservation that is central to his philosophy. Lowe hopes that the attention gained by the Tutankhamun debate will allow him to reproduce the three other main tombs in Luxor: Seti I, Tuthmosis III and Nefartari. He intends to place them next to the Tutankhamun replica at Howard Carter’s house and also hopes to train Egyptians to use his hi-tech scanners.

But the point is not just to save those tombs. It is also to challenge our assumptions of the originality and authenticity of works of art. The idea of visiting a “copied” Valley of the Kings rather than the original one will have many Egyptian and foreign visitors scratching their heads. And no doubt the Egyptian antiquities ministry is not keen on future tourists skipping the Valley of the Kings and instead flocking to Howard Carter’s house to visit the replicas. Is it really the same? Does it hold the same power, or magic, as walking into a tomb that is thousands of years old? In a “tomb or no tomb” scenario, it is definitely better to have these replicas commissioned for future generations than to leave them with absolutely destroyed original tombs.

In 2007, Italian art critic Dario Gamboni said of Factum Arte’s replica of Veronese’s masterpiece The Wedding at Cana, “I would like you to consider that originality is rooted in the trajectory or career of the object – it is not a fixed state of being but a process which changes and deepens with time.”

For Gamboni, the Factum Arte copy that lives in the Refectory in Italy was a more complete and authentic experience than the original painting taken out of its original context and now hanging in the Louvre. There are very important parallels to be drawn with the Valley of Kings. Although the idea of replicating the pharaohs’ tombs, in theory, means that they could be relocated to anywhere in the world, Egyptians can rest assured that although Factum Arte funded the project in Egypt, Adam Lowe has given the copyright to the work to the Egyptian state.

Lowe’s work is necessary because he is preserving Egypt’s heritage for generations of Egyptians. Tucked away beneath the ground of Howard Carter’s house, these replicas could one day represent the most accurate depiction of what these tombs were once like. And in this sense, the issue of whether or not there is another chamber in Tutankhamun’s tomb should not cloud the fact that Lowe should be hailed for his work.

Comments (0)