While main mainstream Italian media consider the attack on the Italian consulate earlier this month an attack ‘directed against Italy as a country,’ as reported by Ansa, the leading wire service in Italy, and the private-owned Italian Il Giornale, relations between the two Mediterranean nations appear unscathed.

Bilateral relationships between the two countries have so far been marked as a longstanding friendship, based on international cooperation for development in rural areas like Fayoum and Upper Egypt and cultural exchange opportunities in the fields of the higher education and culture par excellence.

In an interview with Al Jazeera the day following the attack, Italian Prime Minister Matteo Renzi said: “I am proud of my friendship with [El Sisi] and I will support him in the direction of peace because the Mediterranean without Egypt will be absolutely a place without peace.”

Mainstream international and national Italian media had immediately reported that Da’esh, otherwise known as the Islamic State, were responsible for the attack which left one dead, nine injured and resulted in major losses for the consulate.

Meanwhile, civilians have been warned to keep far from what have been defined ‘legitimate targets,’ namely diplomatic and governments’ headquarters.

In an AP report, Italian Foreign Minister Paolo Gentiloni said the attack was against Italy and that Italy would increase security at Italian sites in Cairo and greater Egypt.

However, it is worthy to point out that Italy’s fight against terrorism in the Mediterranean region is not more crucial or in the frontline when compared to the declared U.S-led war on terror since 2003, or the UK political line in the international and domestic fight against radicalism.

Furthermore, Gentiloni had mentioned on his Twitter account that “this is not a challenge that the West will win by itself. It is a challenge that we will win together with the large majority of the Islamic community and of the Arab governments.”

Yet despite the peaceful relations between the two countries, it was inevitable for the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs after the attack to instruct Italians through its website not to travel to the country.

Unfortunately however, the economic consequences may be even worse than expected should the security threats continue in a country that typically depends on tourism and foreign investments, but has found itself unable to do so in the turbulent years that followed the January 25th uprising.

Undoubtedly, violence must be firmly condemned and measures taken before the attacks escalate in Cairo.

Still, a simplistic reading of this episode of violence is not enough and will not provide the answer as to why the Italian consulate was the target of this violent attack.

Examining ties between Egypt and Italy over the past decade shows no major or minor symptoms of attrition.

Despite Italian media stressing that the attack was a response to the fight against terrorism which Italy is front lining, it is important to look more closely into the context of the attack and the dynamics of terror attacks in Egypt.

Terrorism is driven by two main principles: unpredictability and randomness.

The history of terrorism in the region shows that low-income areas and tourist attractions are the most obvious targets at the basis for collective violence. In a crowded and urban capital such as Cairo, terrorism is, at least theoretically, in that position to escape from total state-imposed controls in order to destabilize and damage the social and political Egyptian fabric by causing casualties.

It is by building on how terrorism works that the IS warnings addressed to Muslims through Twitter -to some extent, as an attempt to limit casualties- effectively contrasts with the political ‘tactic of violence.’

This leads to questioning the extent to which the escalation of attacks in Cairo is effectively an IS-led matrix, as well as whether it obeys precise domestic political goals from which IS benefits. Such benefits take the form of challenging the regime by addressing the demand of Islamists’ legal reintroduction into the social-political fabric. What we know about Da’esh is that it follows indiscriminate use of violence carried out also against intra-Muslim communities.

Additionally, this gives the hypothesis room to also question the extent to which the IS’s virus answers to a logic of global power-contention, in which Da’esh is used as source of global threat in order to create attritions.

A counter-reading to today’s terrorism may show that soft targets (civilians) are at this stage of history not mainly considered in Egypt, differently from 1980s’ and 1990s’ dynamics of terrorism, where soft targets in the country used to be attacked next to hard targets (namely: military and police personnel).

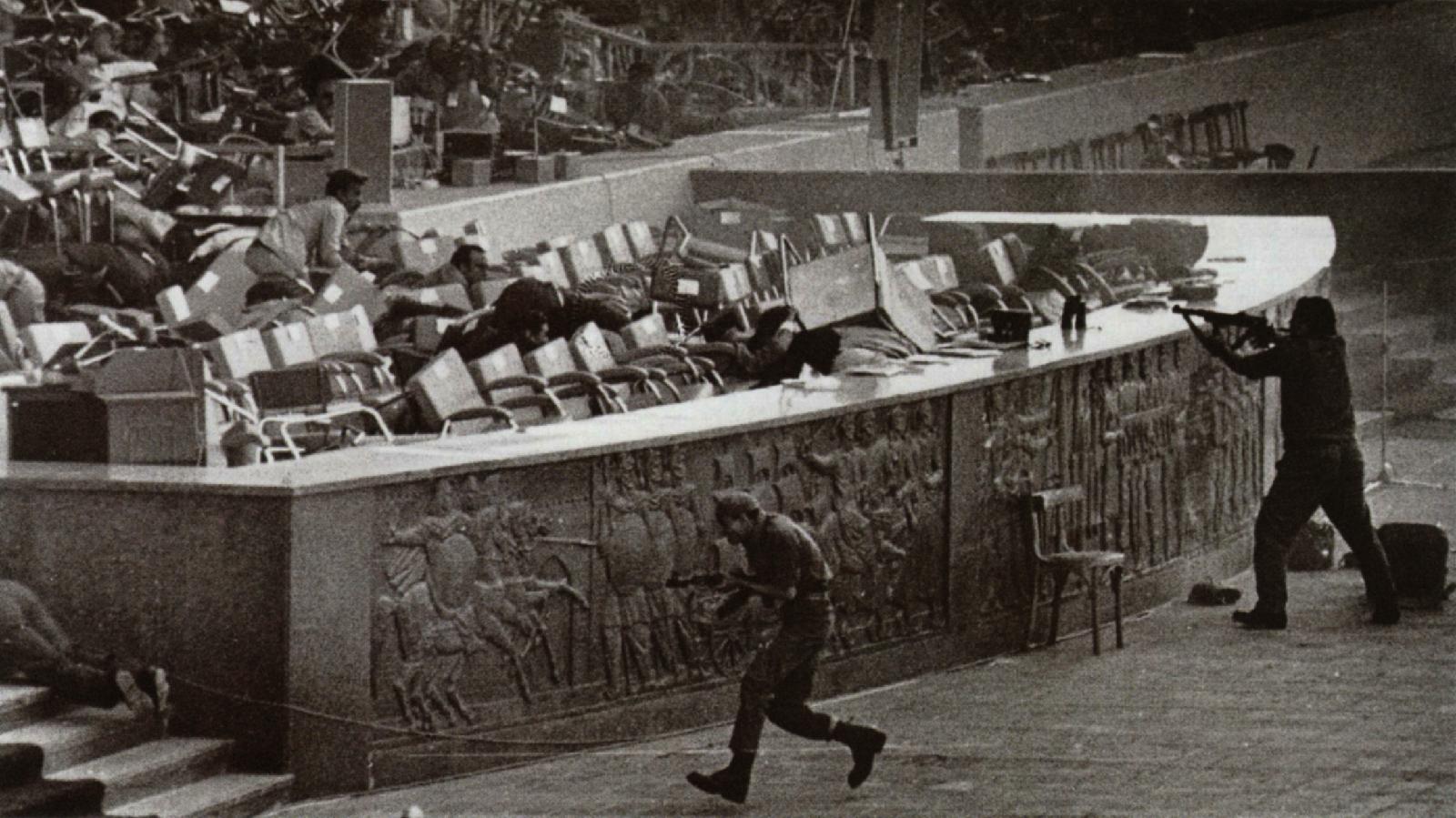

Among the most remarkable incidents of the 1980s’ attacks on soft targets was the 1981 assassination of president Anwar al-Sadat by a member of Tanzim al-Jihad.

Sixteen years later in 1997, an infamous massacre occurred in Luxor –thought to have been instigated by exiled members of Al-Jamaat Al-Islamiyya- reaping the lives of more than 60 people, mostly tourists. At that time and stage of history, soft targets were still a preferable tactic for inciting terrorism.

In addition, ousted president Hosni Mubarak had escaped assassination attempts twice in the 1990s. Broadly, between 1989 and 1999 the number of attacks in Egypt reached 467, causing the country $USD 2 million damage to the national economy (estimated at 15 percent of the GDP at the time).

Today, more than ever, Western state-actors are expected to act in the direction of this crisis management by reassessing political and economic agendas. But more importantly, states are called on to reassess the debate about moderate Islamism and security with intellectuals and spiritual Islamist groups to mitigate and hopefully dismantle the basis for the recruitment of terrorists.

If it is true that terrorism is an equation obeying the equation: L (leadership) added to F (fighters) equals the variable S (strength), then it is by acting globally on the variable S and locally on F that the solution can be found.

Edited by Nadine Awadalla

Comments (2)

[…] What the Italian Consulate Bombing Tells Us About the Latest Terrorism Tactics – Bilateral relationships between the two countries … equation obeying the equation: L (leadership) added to F (fighters) equals the variable S (strength), then it is by acting globally on the variable S and locally on L that … […]

[…] in July, a bomb struck Italy’s Consulate and Cultural Centre near downtown Cairo and Egypt’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The Saturday morning bomb killed […]