A World Bank inspection team arrives at an Egyptian village to assess its transformation of agricultural management. A TV presenter is making a series about women living in the countryside. A group of schoolgirls visits the Agricultural Museum in Dokki and takes selfies with its life size dolls, supposedly representing farmers. Through documenting a series of intrinsically different visits, Azziara (The Visit) deconstructs how stereotypes about the Egyptian countryside are shaped. The film questions the role of mass media, and rural people themselves, in this process.

The main driving forces behind this medium duration documentary are Marouan Omara and Nadia Mounier. Marouan teaches Film Production at the American University in Cairo and directed Crop, his first documentary that was entirely shot at Al-Ahram newspaper’s headquarters. Nadia is a freelance photographer who is into street photography that revolves around the city and the dialogue between the people and the space they move into. Azziara (The Visit) is the result of their first professional cinematic cooperation as a couple, in collaboration with Islam Kamal.

Where does the idea behind Azziara come from?

Marouan Omara (MO): “I was commissioned to make this film by a German organisation that focuses on agriculture. The task was to make a film revolving around the villages in the Delta, and around two elements in particular: water problems and water management, and the problems women living in these villages face and their empowerment. It turned out to be really complicated because the Ministry of Agriculture was gaining more control over the work of NGOs at that time. Because they worked under the umbrella of the Ministry of Agriculture, there were many regulations they were not aware of. We discovered these regulations together, throughout the process. The film project had to fit to their needs yet not cause problems for the collaboratives, the Ministry of Agriculture. That’s why they actually rejected the long version of the film. The scenes they did select don’t contain the visit of the World Bank and the elements that portray the human aspects, and the part of the filming process, which are included into Azziara.”

Nadia Mounier (NM): “Their version is 13 minutes, while the one we have is 43 minutes. We knew they wanted a video of 15 minutes, but throughout the process we decided it would be a good idea the extend the duration of the film to more than 20 minutes.”

MO: “The fact that the long version was rejected gives you a slight view on how NGOs work in Egypt, and how the ministries work. It adds another perspective to their version and it makes Azziara more authentic.”

Let’s go back in time. How did the process behind the film start?

MO: “From the very beginning I decided to work with Fig Leaf, an Alexandrian film company, because they were more aware of the places we were going to film than I was at the time, and to get permits and access to the people living there. Then I started thinking about the place, the villages, and how I could imagine the film to be. From day one I was expecting the film to have some kind of absurd feeling. This is exactly what shines through in Nadia’s photography work. Wherever she goes, she can just get out her phone and take a picture of something of which people would question its importance. But once you look at the final result, you ask yourself how she managed to get all those elements included in one frame. I was exactly in need of that element, the out-of-the-ordinary in a place. But she refused at first…”

NM: “…Because videos have the type of exposure photos don’t have, and filming is a long term process of working on the idea and the shooting itself. It’s also never a one-man show. With videos you always work with a team, whereas I am used to working by myself.”

A substantive part of the couple’s pre-filming research comprised of visiting villages on the Egyptian countryside every weekend over the time span of two months. In Damanhour, Kafr El Sheikh, Baheira, Beni Suef and a number of other places, they spent several days – without microphones or cameras – to collect interesting stories, ideas, and metaphors.

What do you aim to convey with this film?

MO: “The core message is about the media and their power. It is about how the media manipulates. Going from Cairo, where we have been living our entire life, to Kafr el Sheikh was an experience in itself. I remember that when we’d go there, I would be looking around looking for villagers, cows… But instead I saw very tall buildings, BMWs, asfalt everywhere… I had expected to see something totally different: an open landscape with farmers, villagers… The farmers are not wearing galabeyas anymore – they’re wearing jeans. They are farming but they have Android and Facebook. I came with a stereotype image in my head myself, which is built on what I have seen on TV. Going there, I didn’t go to the village I used to see on TV. This was the case in all of the villages we visited.”

NM: “This is also another layer within the title: our crew were also visitors, commenting on the differences we’d see, just like the World Bank visitors, the school girls at the museum, and the presenter and her crew.”

MO: “This is also why I am not sure that what we show through this film is reality. It’s still a selection, our selection.”

Could you explain the presence of the TV presenter in Azziara?

MO: “By making this film I discovered that there is a TV channel called Masr El Zaraʿeya. It is the only TV channel focusing on agriculture and farming in the Middle East. Their headquarters are located in the Ministry of Agriculture building in Dokki. When I met them I talked about my idea for the film, how I thought media misrepresented the village, and how I wanted to do something different. We met the TV presenter, Abeer, and decided to follow her and her crew while making a TV program.”

NM: “When the people of the village noticed a camera and a TV presenter, they took us more serious. They were more tended to answer questions and complain about their life. It was difficult to get information from them during our research trip because they were rather suspicious. In every house, as basic and simple as it could be, you would find a TV. So tagging along a TV crew really made a difference.”

MO: “By getting in touch with this TV channel we found out that their film crew meets every two weeks, when they go on a trip for one day to shoot four or five episodes at once. The presenter is making a series called Sitt el Dar, about women in the villages. She interviews them but she actually uses more general, expected questions.”

NM: “The difference between them and us is that they are part of the media that produce these stereotypes. The presenter kept on making the same kinds of representations and she was searching for the same kind of problems and people. Even the people themselves gave her the expected, cliché answers.”

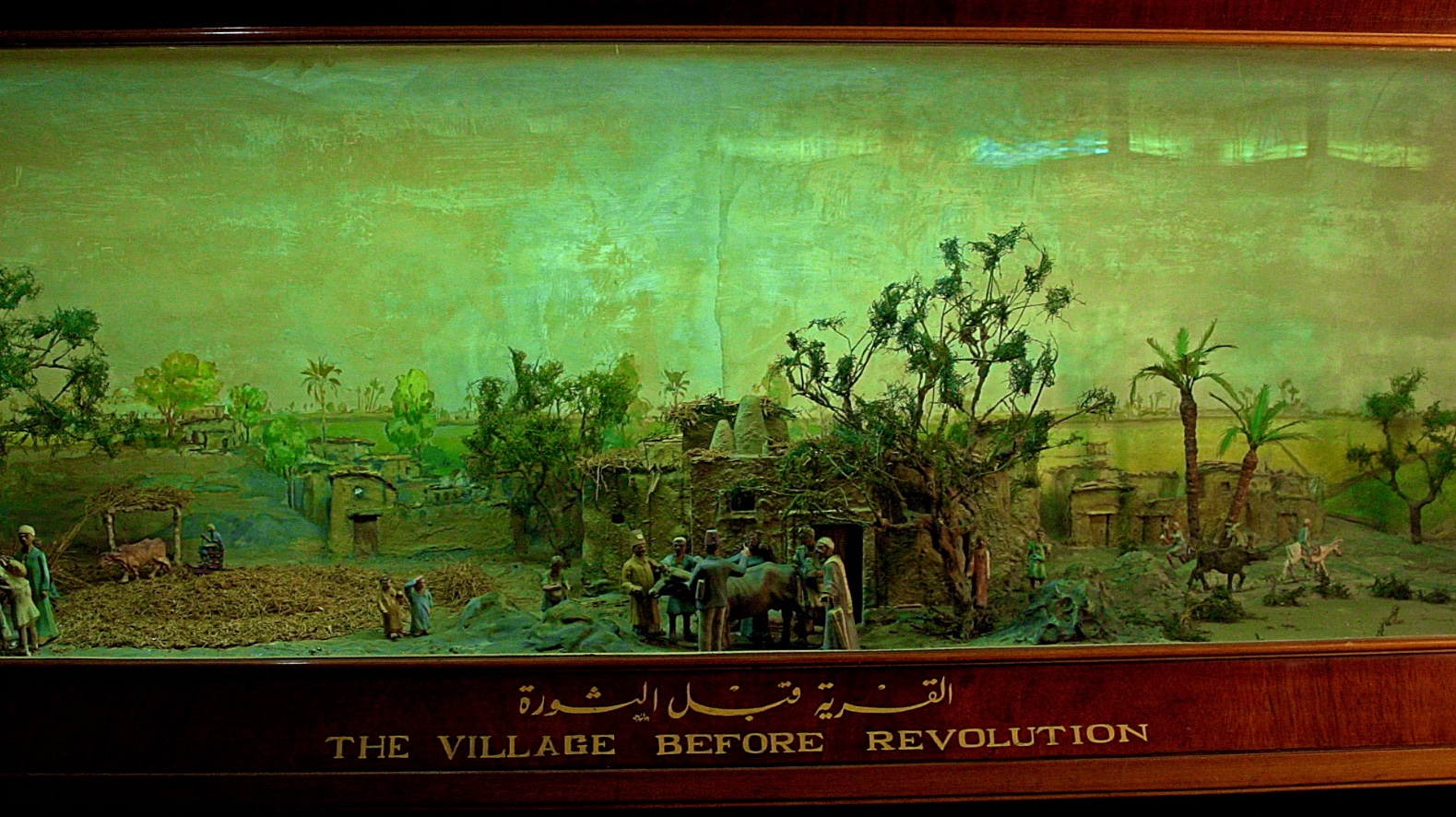

Why did you decide to film at the Agricultural Museum in Dokki?

MO: “During our brainstorm sessions we realised that this museum is the only key for any Egyptian living in the city to know about the villages. It’s either the museum or TV.”

NM: “This became particularly clear after we started editing the material we had from filming in the villages. Going to the museum offers the same cliché image – and when the students take pictures with the statues at the museum only highlights this idea. The Agricultural Museum offers the same expected window to the countryside as TV does, through series and even independent films up until today. This representation is what we would like to deconstruct.”

Do you think you will be able to battle these stereotypes through your film?

MO: “We try. I’m not sure if it will work. We offer a different image so the spectator can question the media, what the farmers say, and to which extent NGOs and the authorities are doing their jobs. We are just questioning.”

Is the scene with the TV presenter at the museum the only fictional one?

MO: “Nothing in the film is purely documentary or fiction. We invited the TV presenter to be a part of our film doing what she used to do in her TV show, while we just provided her with the outline characters and locations that we would like her to meet and be at.”

Is there always a connection between the dialogues and the scenery images in between?

MO: “Metaphorically, yes. Sometimes it’s very direct, at other times it’s indirect.”

NM: “The visual aspect also counts. To us elements such as the water tower and the electricity tower are like representations of the state. Our colleague Islam Kamal was very good at selecting these images and putting them in order. The tempo of some scenes is very fast. Others are slower to give more time to observe, and to give those who are not familiar with these areas a sense of them.”

MO: “Another goal of these scenes is to give the viewer a new perspective on the landscape of the villages. And to reshape the actual image of the village we are used to.”

—

Azziara (The Visit) will be screened at the Luxor African Film Festival (17 – 23 March 2016), at the Netherlands-Flemish Institute in Cairo (20 March), and at the Göttingen International Ethnographic Film Festival (4 – 8 May 2016).

Comments (0)