For years, Egypt’s music industry has always been largely supported and produced by the government. From the likes of Abdel Halimm to Um Kulthum, who were key players in promoting nationhood and “al musiqa al arabiyya” (Arabic music) to achieve soft power in the Arab region, music no longer came to symbolise art, but a symbol of the nation.

While it is true that all arts are largely shaped by a society’s culture and identity, many forget that art should mean freedom. Music is freedom. It does not need to express any nation or any flag, but simply the people that perform and enjoy it.

This freedom for Egypt’s metal fans faced many setbacks. In the early 1990s, Egyptian state newspaper Rose Al-Youssef published a ‘study’ on youth who dressed in black, wore piercings and listened to metal. The article linked the metal fans to Satanism, which sparked a reaction from the state and led to the arrests and shutdown of many concerts.

Later in 1997, the issue skyrocketed. Security forces arrested more than 100 young metal fans and charged them with promoting Satanism. While they were eventually released due to lack of evidence, they still faced huge criticism and opposition by the media.

Of course, the loud music, frenzied dancing, Baphomet shirts and use of dark imagery can create an uncomfortable and scary atmosphere for many Egyptians. However, this is only a superficial understanding of the genre in general, neglecting the fact that, just like other music genres, it also serves a purpose and has its own unique composition.

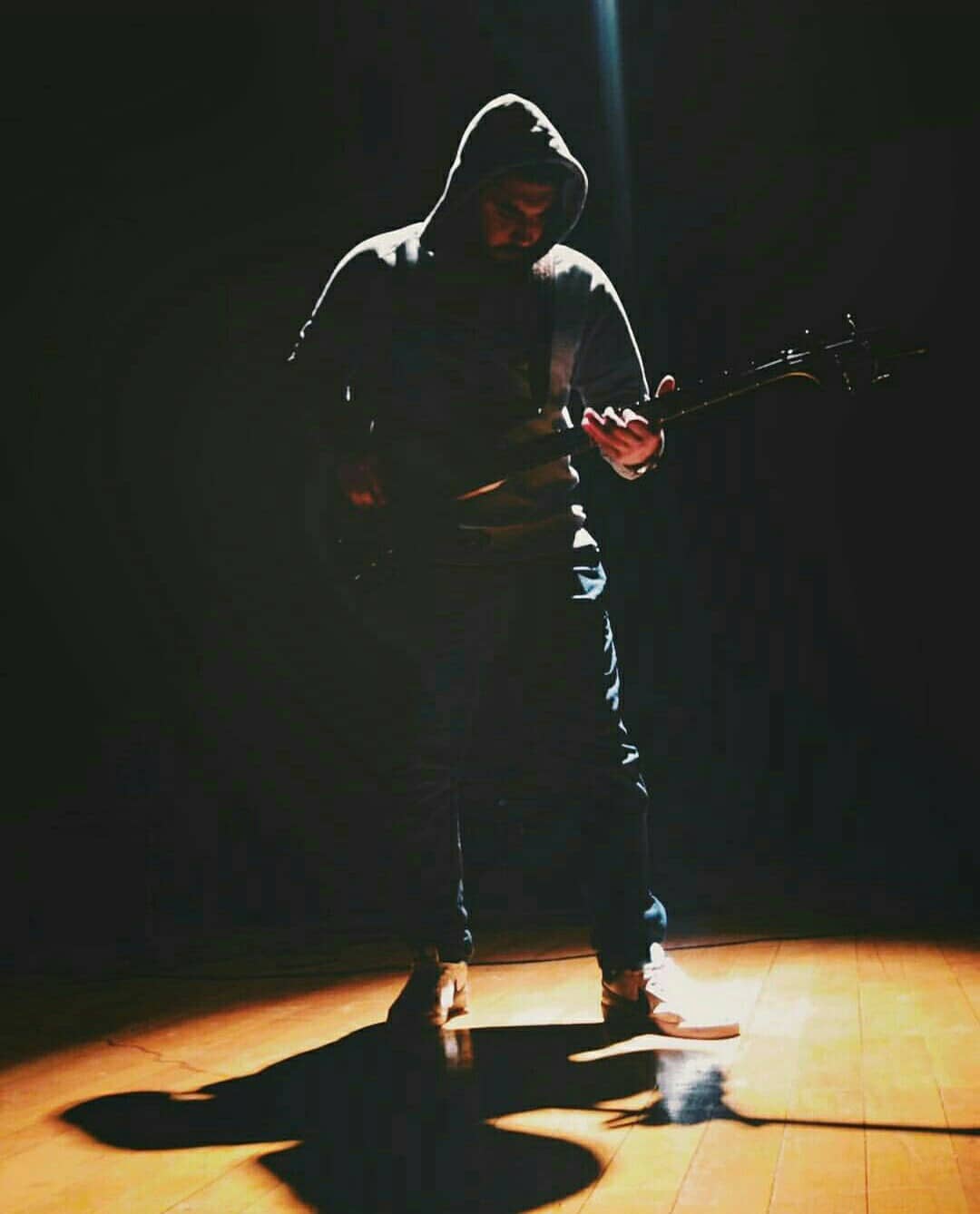

“Don’t judge what you don’t understand,” Omar Monem says, a recent graduate and founder of Egyptian based hard rock/heavy metal band Dystopia. Since birth, he always had a passion for metal music – particularly heavy metal – and despite studying Business Administration at university, this did not prevent him from taking a step further to create his own band.

Monem explains that the music composition of metal music, which includes the lyrics and the sound, the lyrics need to send a message, a story or a purpose to tackle an issue in society.

“For instance, the song ‘Aces High’ by Iron Maiden, an English heavy metal band, tells the story of a British RAF pilot fighting during the Battle of Britain in 1940, which was an event in history the the British were particularly proud of,” he says.

“Another song is ‘Master of Puppets’ by Metallica, which tackles the harms of drug taking and how drugs can have the power to control you, as seen in the title of the song.”

If metal music, then, can indeed have such positive messages to send to the society, then why does it remain unpopular and attacked in Egypt?

“Music here is constricted to one genre, people are used to the old school romantic songs with the same rhythm and beat, and even when new bands like Cairokee tried to enter the scene with a new kind of style, they faced many problems in the beginning until the younger generation gave them space and accepted them,” Monem explains to Egyptian Streets.

“Culture is also a big challenge, as it is not really in line with Egypt’s folk music and it did not yet develop to include songs with Arabic lyrics, it is still very much played in English,” he adds.

“Finding places to play is also still very difficult, apart from Zamalek’s art venue El Sawy, and there isn’t enough support or finance to help the bands become more mainstream or popular.”

Despite the challenges, however, the metal scene still has hope to witness a revival. In 2007, two international bands performed in Cairo, including Wyvern, a leading metal band in Egypt, as part of the SOS music festival.

Moreover, in 2011, the Metal Blast concert attracted almost 1,000 fans at El-Sawy, followed by an entire metal festival a month later, which was covered by state television.

For young metal fans aspiring to become musicians, Monem tells them to “never lose hope” and “to always invest in your passion, but to acknowledge that there is still a ceiling that many tried to break before you.”

It is not just the ceiling for metal music that must be broken, however, but the ceiling for expression, art, and freedom.

Comment (1)

[…] Source link […]