During high-school, in Kuwait, we would chant We Will Rock You to intimidate our opponents, and later chant We are the Champions to declare victory. I also remember quizzically wondering if Queen really did in fact sing bismillah in Bohemian Rhapsody. And though, back then, I could sing along to many of Queen’s songs with no memory of when I learned the lyrics, I knew nothing about the band members until I watched the biopic, Bohemian Rhapsody, in the theaters. Outrageous, I know.

Is this the real life? Is this just fantasy?

When Rami Malek won the Oscar – and earlier the BAFTA and Golden Globe – for Best Actor for his role in Bohemian Rhapsody, I woke up the next morning to a bustling Facebook newsfeed. There were aunties, uncles and friends, as well as cultural and political organizations – homophobic and not – claiming Rami as one of their own: A Copt! An Egyptian! An Arab! After his recent success, their Facebook posts were accompanied by a selection of Rami’s speech: “I am a son of immigrants from Egypt, a first-generation American, and part of my story is being written right now.” With minimal visibility of Egyptians, and especially Copts, in Hollywood, many have taken to social media to celebrate how Rami has achieved the alleged American Dream. Even AMIDEAST.Egypt comically shared an image of Rami Malek holding his Golden Globe to advertise their English language courses as a pathway to global success.

Open your eyes, look up to the skies and see…

I am struck by the widespread intensity of praise and applause.

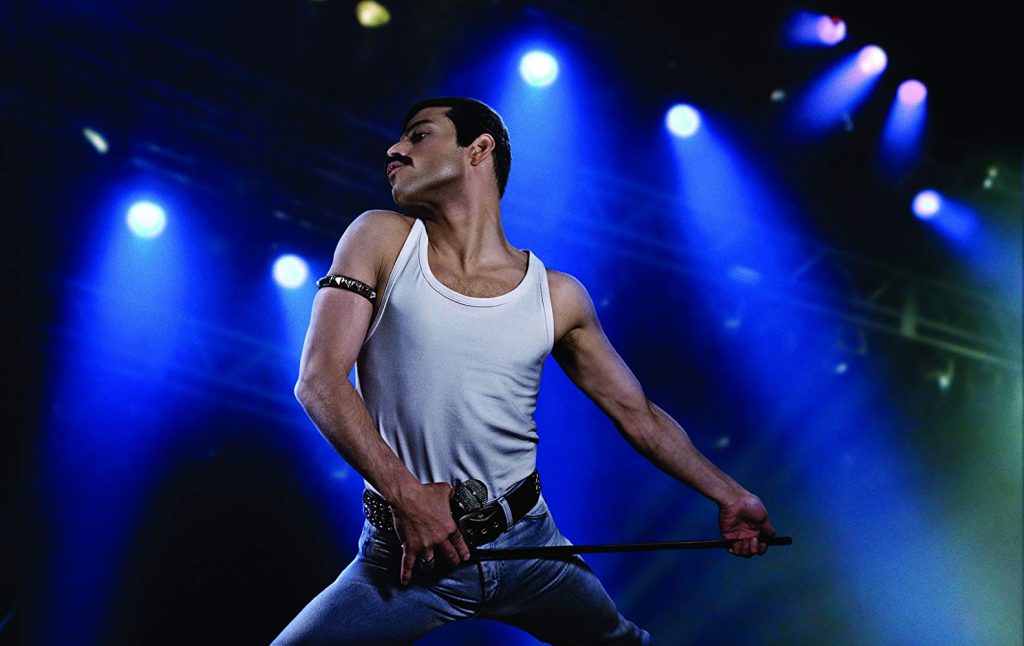

Rami Malek owes his recent success to his role in Bohemian Rhapsody as Farrokh Bulsara, popularly known as Freddie Mercury, the lead singer of Queen. Freddie, too, is a story of immigration and success; he is a descendent of Parsi Indian parents who moved to Zanzibar and later settled in England. To date, Freddie Mercury is widely regarded as one of the greatest singers and performers of all time. What is striking here isn’t the celebration of Rami’s success. Rather, it is the utter invisibilization and outright denial of queerness.

Unlike Rami, Freddie is bisexual. And unacknowledged in the celebrations of Rami’s success is the significance of representing the sexuality of a brown immigrant on screen. My Facebook feed is engulfed with images of Rami Malek winning awards, and none of his role playing Freddie Mercury – a flamboyantly androgynous and queer legend.

Erased from their Facebook posts – intentionally, I think – is part of Rami’s speech where he emphasizes that the film is, indeed, “about a gay man, an immigrant, who lived his life just unapologetically himself.” The selective celebration of immigration and not of queerness is blatant, and the heroization of Rami Malek as an immigrant makes me wonder if he would have been so quickly claimed as “one of us” had he, himself, been queer.

Bismillah! We will not let you go. (Let me go!)

Will not let you go. (Let me go!)

Perhaps, in some ways, Rami Malek has also contributed to the invisibilization of queer people. He belongs to a legacy of straight and cis actors who have won Oscars for playing queer roles. Additionally, while Rami has acknowledged his Egyptian and Coptic origins – and quite charmingly so –, and also even nodded to the violence against Copts in Egypt, he has remained deafeningly silent about the horrific crackdown on queer individuals in Egypt. For years, while LGBTQ+ Egyptians have been incarcerated and tortured en masse, the Coptic Church and other religious institutions have held conferences to “treat” homosexuality.

So you think you can stone me and spit in my eye? So you think you can love me and leave me to die?

Once, I watched a Coptic Orthodox priest tell a room of high-schoolers that no queer Copts exist. He said this during Sunday School, in front of a room that was undoubtedly inhabited by queer and questioning Copts. The claim is outrageous, and it both denies the existence of queer Copts and justifies rampant homophobia and transphobia within Coptic communities. To combat such instances, recent efforts by Coptic Egyptians – namely CopticQueerStories and LGBT Coptic Christians – have sought to elevate the existence, reality and theology of queer Copts. These platforms highlight the struggle of queer Copts who often feel like they are “the only one” as they navigate and juggle their multiple, and seemingly competing, identities.

So, in his speech, when Rami Malek says that “we are longing for stories like this”, indeed, we are. We are longing for queer, brown and immigrant success stories. And I am longing for a Facebook feed, and broader communities, that celebrate immigration without invisibilizing and erasing queerness. Any way the wind blows.

Comment (1)

[…] Source link […]