Bridges old and new adorn the city of Cairo, crossing the Nile river and serving to connect the city’s constantly expanding and newly emerging districts.

While they are indispensable for enabling movement between certain neighborhoods as well as for dispersing the city’s heavy traffic load, they also carry broader historical and cultural significance. Looking into some of the stories behind their construction and taking a glimpse at the various key stakeholders involved, reveals much about modern Egyptian history and politics.

The very recent inauguration of the Rod El-Farag Bridge by President Abdel-Fattah El Sisi on 15 May once again drew nation-wide – even worldwide – attention to the huge construction work currently underway in and around Cairo; the bridge was notably entered in the Guinness Book of World Records as the world’s widest suspension bridge to date.

The Rod El-Farag Bridge, which has come to be named the Tahya Masr Bridge (‘Long Live Egypt Bridge’), is one of the latest ambitious infrastructural projects to have been inaugurated by the Egyptian leadership. The six-lane, 540-meter long and 67.36-meter-wide suspension bridge was completed in a mere 32 months, requiring a total of 4,000 Egyptian technicians and engineers.

Costing six billion Egyptian pounds, it was built by the Arab Contractors Company, which began working on the bridge back in 2016 under the supervision of the Armed Forces Engineering Authority. The main vision driving its construction was that it would reduce traffic congestion along the 26 July Corridor and 15 May Bridge.

The Arab Contractors have in fact dominated Cairo’s bridge-building scene for a while, with many of the more recent bridges and bridge renovations a product of their vision and labor.

Established in 1955 by the Egyptian entrepreneur Osman Ahmed Osman, the Arab Contractors (AC) is one of the leading construction companies in the Middle East and Africa, working in more than 29 countries, according to their website. They focus on projects including public buildings, bridges, roads, tunnels and airports, among many others. The company notably participated in the construction of the Aswan High Dam and provided surface-to-air missile bases in the 1973 War.

Besides the most recent Rod El-Farag axis, the 6 October and 15 May bridges, alongside several others, were crucial national infrastructure projects that the Arab Contractors played a role in.

6 October Bridge

Considered the main artery of Cairo, the 6 October Bridge crosses the Nile twice, connecting the western Agouza district to Gezira Island and then Downtown, before proceeding to the Cairo International Airport towards the east.

Its name is inspired by and meant to commemorate the date of 6 October, when Egypt defeated Israel in the 1973 October War. Its name also evokes the 6 October 1981, when former Egyptian president Anwar Sadat was assassinated. During the January 2011 Revolution, the 6 October Bridge constituted the main route to Tahrir square, itself even becoming the scene of protests.

This bridge was constructed by the Arab Contractors over the course of nearly 30 years, from 1969-1996, albeit distributed over various phases. It was not until 2005, that Phase 9 completed the final 21.1-kilometer-length bridge, rendering it one of the longest bridges in the world. Since its opening, it has become one of the most important bridges in the capital, with around 500,000 people crossing it every day.

If we look further back to the beginning of the last and even the late 19th century, however, it was mostly foreign construction companies that were influential in the sphere of bridge-building in Egypt.

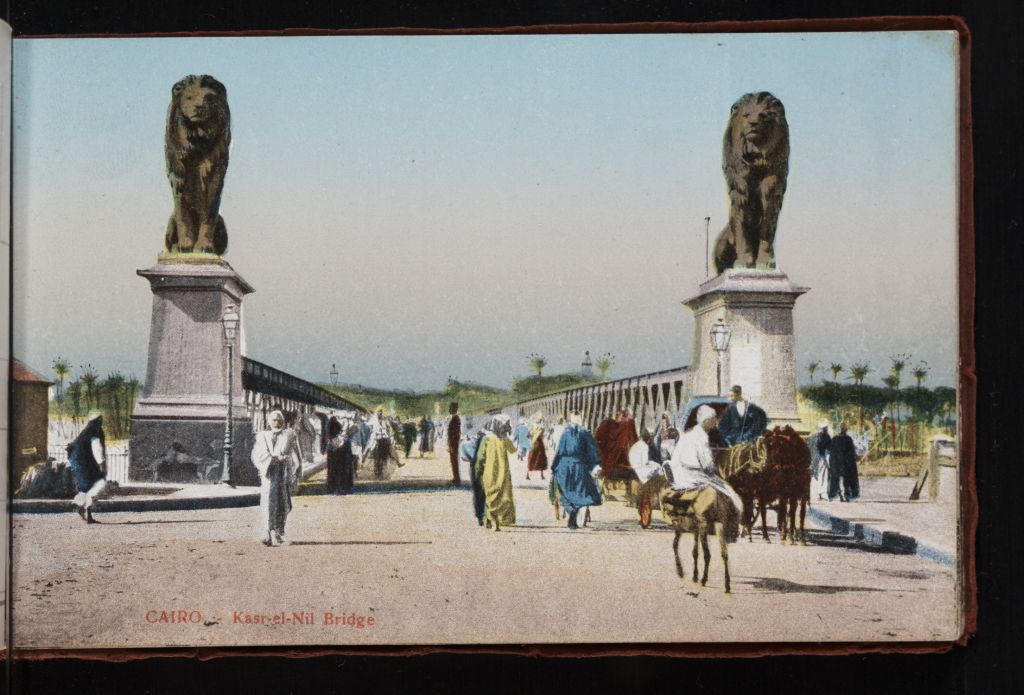

Qasr El-Nil Bridge

The idea to build the Qasr El-Nil Bridge – Cairo’s first ‘modern’ bridge to cross the Nile – stemmed from Ibrahim Pasha, son of Mohamed Ali Pasha, and formed part of a larger 19th century vision of rebuilding Cairo.

Once Khedive Ismail came to power, he placed the construction in the hands of the French, commissioning a bridge across the Nile in central Cairo, one that now links the Cairo Opera House in Zamalek to Tahrir Square downtown.

The first of two construction phases took place as early as from 1869-1871, with the bridge opening to the public in February 1872. Linant de Bellefonds, who was the chief engineer of Egypt’s public works from 1831-1869 as well as an influential engineer of the Suez Canal built the bridge with the participation of the French Five-Lilles Company.

After 60 years in operation, the Qasr El-Nil bridge had to undergo intensive renovation; the newer version that was built in its place between 1931-1933 was built on a steel frame, making extensive use of concrete and weighing around double the weight of the older one at 3,360 tons. This time the British engineering company Dorman Long and Co. was put in charge. Having started out as a major steel producer in 1875, the company soon diversified into bridge-building. It is the same company that built the famous Sydney Harbour Bridge in Australia as well as London’s Lambeth Bridge, among many others.

Naming it after his ancestor, the Khedive Ismail, King Fouad inaugurated the new bridge in 1933. It was only following the 1952 Egyptian revolution, that it took on its current name, Qasr El-Nil Bridge (Palace of the Nile), derived from the palace that Mohamed Ali Pasha had built for his daughter Princess Nazli, allowing her to live on the banks of the Nile.

Boulaq Bridge

The Boulaq Bridge which, having been demolished in 1998, in fact no longer exists today, similarly underwent several name changes, being renamed to Fouad Bridge and then later to Abou El-Ela Bridge.

Also crossing the Nile river, by linking Gezira Island to Boulaq, this bridge was designed by the American engineer William Donald Scherzer (1858-1893), an engineer known for having invented the so-called rolling lift bridge. As such, it seems only fitting that the Boulaq Bridge too, had a rolling and locking mechanism allowing it to open to river traffic.

Actual construction was conducted over the course of three and a half years (1908-1912) by the two French metal construction companies, Five-Lilles and Schneider, the former producing the bridge’s steel girders, the latter its beams. Opened to the public in July 1912, the bridge ultimately measured 274.5 meters in length and 20 meters in width.

Imbaba Bridge

One of the more mysterious cases of Cairean bridge-building, in that its original designer seems not to be known, or at least agreed upon, can be found in the Imbaba Bridge. Rumors even suggest it was designed by the famous French engineer, Gustave Eiffel.

The only railway bridge to cross the Nile, it witnessed two versions, similar to the Qasr al-Nil bridge. The older construction was completed in 1890, measuring roughly 495 meters in length, and designed to allow railways to cross the Nile River heading westwards to the Giza Train station.

While the older one was still in operation, the new Imbaba Bridge as it is currently known, was constructed, between 1912-1924 and during the reign of King Fouad the First, son of Khedive Ismail. Yet it was halted midway due to WWI.

The Belgian engineering firm Baume-Marpent was contracted to build this new version of Boulaq Bridge, which would include two railroad tracks, two passages for vehicles as well as two passages for pedestrians – an expansion demanded by the rapid increase in traffic across the bridge. Baume-Marpent was in fact one of the most important railway construction firms in Belgium and in Egypt, according to Karima Haoudy, who works in the Ecomusée in Belgium that holds one of the firm’s most important archives. “In fact they built more than 158 bridges in Egypt.”

There is much left to be said about and added to the history of bridges and bridge construction in Cairo. What a preliminary glance at the various construction companies and stakeholders involved reveals, however, is that bridges have generally reflected a dominant vision of their time: both in terms of architectural style and in the purposes they were meant to serve.

In a constantly expanding city like Cairo, one might wonder how many more bridges will become necessary in the future and in whose interests they will be built.

Comment (1)

[…] handed a certificate to the new Rod Al Farag Axis Bridge in Egypt for being the widest cable-stayed bridge, which measures 67.3 m (220 ft 9.6 in) […]