Only eight African countries have national pavilions at the 2019 Venice Biennale. At this year’s Cairo International Fine Art Biennale (Cairo Biennale) we have ten, including Algeria, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Cote d’Ivoire, Morocco, Nigeria, Senegal, Tunisia, Uganda, and Zimbabwe.

Having said so, black and African artists still face many challenges, despite a recently surging global interest in African art. It is not always easy to fund African artists’ participation in exhibitions outside of their continent. Finance is one issue, but political instability in some countries leading to prolonged power struggles that affect the normal functioning of cultural agencies is another.

Against this backdrop, Cairo has the unique advantage of its geographical proximity, prevailing artisanal traditions, the relative depth of its art industry as well as the willingness of cultural professionals and institutions to support one of the oldest biennales in Africa and the Middle East.

The recent focus of the media and market on art created by black and African artists comes as a result of decades of patient advocacy and persistent hard work by generations of thought leaders and publishers, including Okwui Enwezor and Simon Njami (Revue Noire).

Egypt’s warm embrace and strategic interest directed at countries beyond her southern border is not a new phenomenon, yet is the first time since the founding of the AU in 2002 that Egypt is heading the organization. Egypt’s President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi took over as chair of the African Union (AU) this year, taking the helm from Rwandan President Paul Kagame.

In his 1964 memorandum (No. 1-64) to U.S. President Lyndon Johnson, Yale history professor and former CIA intelligence analysis director Sherman Kent suggested that Egyptian president Gamal Abdul Nasser had made multiple attempts and plans to expand and strengthen his nation’s African relationships. As an avid supporter of the non-aligned movement and anti-colonial efforts, president Nasser strove to achieve a larger role in the ‘freedom fight’: for himself and for Egypt, against the South African government as well as Portugal’s continued entanglement in Mozambique and Angola.

Half a century ago, Nasser’s African dream was miffed by what at the time was still existing distrust between black Africans and Arabs due to the history of slave trade and the challenges brought upon by religious differences. It remains to be seen if political ambitions and economic necessity will lead to the cross-fertilization of contemporary art scenes across various African art hubs.

After a 10-year hiatus, this year’s 13th Biennale entitled “Eyes bound East”, which is curated by Ehab Ellabban, is scheduled to open on 10 June for two months.

Founded in 1984 and organized by the Ministry of Culture, the Cairo Biennale is a comprehensive contemporary group art exhibition. Past exhibitions have received their share of criticism, from lacking transparency and efficiency, and making anachronistic thematic choices, to the committee’s apparent overemphasis on the more traditional art practices of painting and sculptures.

This year, head curator Ehad Labban has promised to deliver a more artistically diverse, inclusive, and socially relevant exhibition. Regarding the theme “Eyes Bound East,” a selection committee member commented: “It is not necessarily a focus on our eastern neighbors of Saudi Arabia or China, it is more about looking past our traditional partners and standard mode of thinking.”

What are Egypt’s alternatives, options, and opportunities? Where do we go from here? Where will our new collaborators China, Japan and South Korea take us? How about our brothers and sisters along the tributaries of the Nile and beyond?

This year’s participants notably include the following African artists:

Admire Kamudzengerere (Harare, 1981) is a multimedia artist from Zimbabwe, who experiments with a self-adhesive memo pad and sticky notes to create a wall; through this, he exposes his inner psychology, the political struggle of his personal histories as well as the parallel narratives of society and his country.

Ivorian Artist Ernest Duku (Abidjan, Paris, 1958) is fascinated by “the cultural chaos of African countries after independence.” His triptych “Kolonial Alite code A”, “Kolonial Alite code J.C” and “Kolonial Alite code M” comment on the relationships and interactions between civilizations, colonial legacies, technological development, and spiritual beliefs visualized through the mystical puzzle of numbers, symbols and DNA codes.

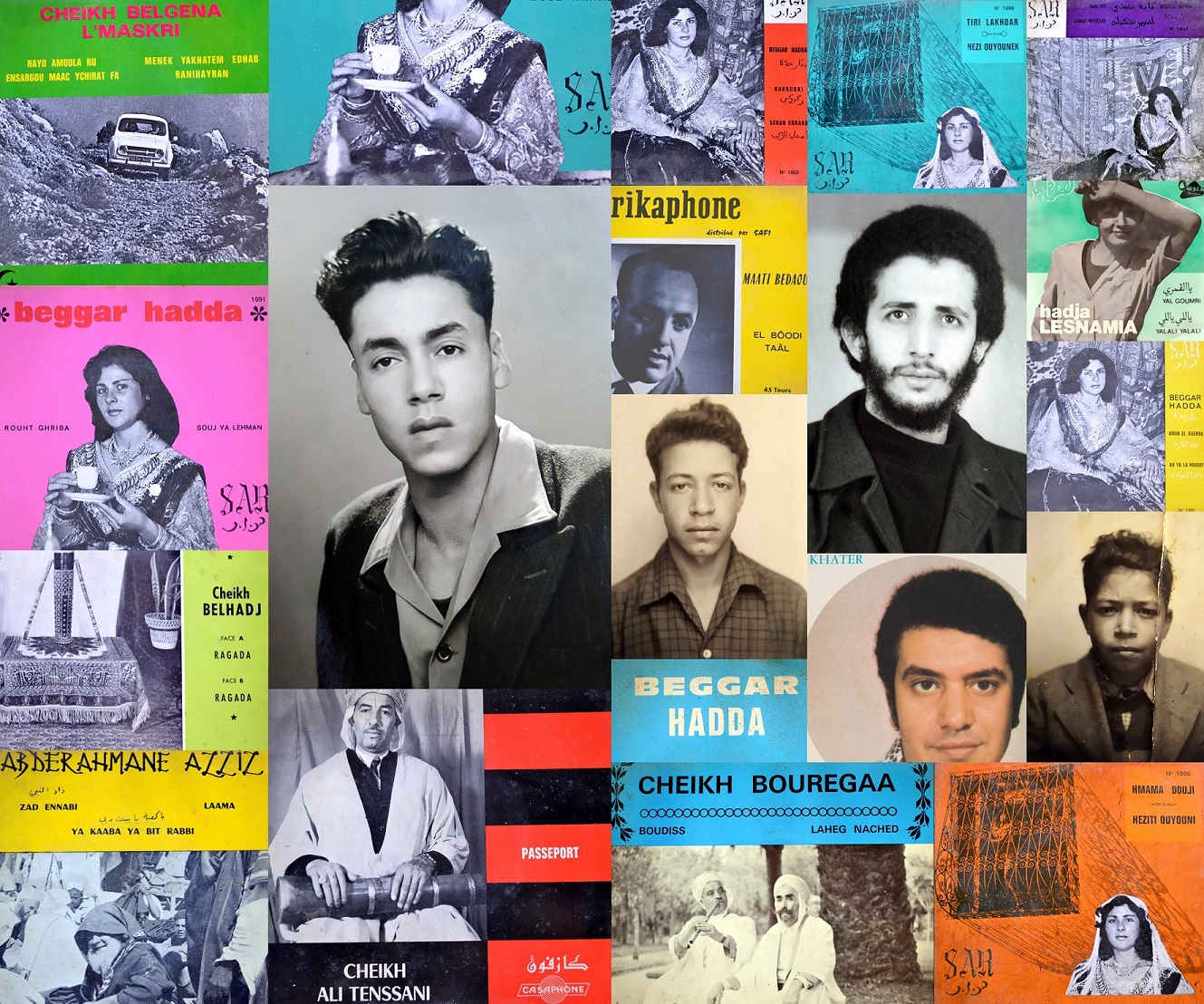

Algerian artist Amina Zoubir (Algiers, Paris, 1983) will be exhibiting her older work “Erase Female Body”, which raises awareness about the patriarchal codes that encourage the infantilization of both women’s spirits and their bodies. In her more recent work “Last Pop Dance Before Darkness” Zoubir shows dancers in unpublished scenes, witnessing Algerian pop music during the 1980’s before the civil war a decade later. With her photography installation “Muscicapidae” she pays homage to her ancestors and predecessors who contributed to the preservation of her country’s unique Berber and Arab heritage.

In addition to these African artists, the Biennale will also be exhibiting work by Omar Ball (Mauritania, 1985), Antoine Tempe (France, Senegal, 1960), Serigne Ibrahima Dieye (Senegal, 1988), Hyacinth Ouattara (Burkina Faso, 1981), Sanaa Gateja (Uganda, 1950), and Mohamed Bourouissa (Algeria, France, 1978).

During the Cairo Biennale, the capital’s dozens of galleries and art centers such as Gypsum, SOMA, and Zamalek Art Gallery will be organizing parallel exhibitions. At the contemporary art and cultural center Darb 1718 for instance, “Roadmap to the Renaissance” is showcasing 13 young and emerging Egyptian artists, taking the pulse of the current mood and undercurrents of society.

“Eyes Bound East”, 13th Cairo Biennale 2019, Palace of Arts, Cairo Opera House, 10 June to 10 August 2019

“Roadmap to the Renaissance”, Darb 1718, Old Cairo, 11 June – 11 August 2019

Comments (0)