Known as the capital for various forms of arts in the entertainment industry, Egypt has become known for its belly dancing providing an opportunity for female performers to advance the entertainment industry.

Although there is a constant debate on the origins of belly dancing, the art was, and still is, eroticized by many travelers and tourists, some of which visit Egypt just to explore that scene.

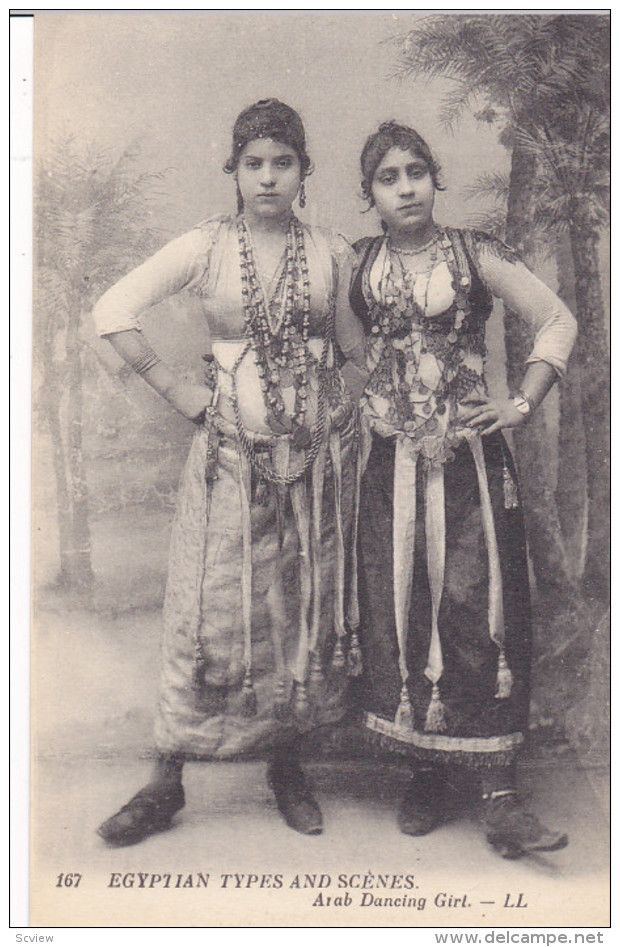

The origins of the dance in Egypt can be traced back to the 19th century, where there were two groups of women who participated in the entertainment industry; ‘awalim’ and ‘ghawazi’.

The ‘awalim’ were a group of scholarly women who wrote poetry, sang songs and composed music, and improvised lyrics for ‘mawal’ or ballads, a feat they were highly valued for. They were an exclusive celebrity-like group who performed in the harems in the presence of women only, however their voices were audible by both women and men.

The ‘awalim’ were not accounted for in any travelers’ book. Perhaps because the travelers have not been exposed to them. The other group of women were called ‘ghawazi’ who mainly danced unveiled in public spaces like coffeeshops and performed in occasions such as ‘mulid’ or public celebrations of feasts. They were described in the travelers’ accounts as a “separate time, as Gypsies or gypsy type wanderers”.

Some of the traveler’s descriptions, such as that of Swiss historian Jacob Burckhardt, are not very accurate. His description almost resembled an “inversion of the usual mode of like amongst Egyptians,” as Kathleen Fraser writes in her book ‘Before They Were Belly Dancers’.

It is mentioned in Burckhardt’s account that the ‘ghawazi’ were prostitutes who married within their communities. He also noted that ghawazi were given away by their fathers to marry the highest bidder.

Burckhardt noted that after marriage, the ‘ghawazi’ continued to dance and work as sex workers while their husbands depended on them for “food, cloth and protection.” They were servants, musicians, and pimps, according to Burckhardt, and the ‘ghawazi’ could renounce them at any time.

Other early travelers described ‘ghawazi’ differently, depicting them as only dancers whose most striking features were their unveiled faces.

Some mentioned that these women had nose rings and tattoos and performed with different objects like “scarves, sticks, and sabres,” which, along with their performances of local dances, made them more admirable.

A more of a hybrid category between ‘awalim’ and ‘ghawazi’ also existed. Some ‘awalim’ were a lower class who performed for “the poor in the working class quarters,” resembling some of the ‘ghawazi’. Meanwhile, there were ‘ghawazi’ who sung like the ‘awalin’.

However, as many travelers were not familiar with the lingo, it caused confusion in their accounts, preventing them from forming a distinction between the two forms of entertainment.

Historians resort to this because it facilitates the study of each group and establishes a common characteristic or persona for all its member or participants, while in reality, it is never black and white. There is always a grey area in the middle that is lost in these distinctions.

One of Egypt’s most famous and written about belly dancers in the 19th century, Safiyya of Esna, practiced the profession for more than 20 years, from 1830 at the young age of 15 to 1850.

Fraser collected the memoirs of Combes, Didier, Flaubert, Hamont, Prisse d’Avennes, Romer, Eliot Warburton, and Bayle St. John who wrote about Safiyya to compile them together and make and extensive biography of her.

On the other hand, their memoirs are written from a personal perspective and their portrayal of Safiyya is subjective.

Flaubert’s account indicates that Safiyya was still in Esna during March 1850, however, according to Bayle St. John’s account, Safiyya had “retired to a respectable marriage.” St. John criticizes her marital choices and life by saying her fame and money probably attracted her new husband.

Although Combes wrote about her body and its movement to the music and his admiration of both, and Romer wrote about her fame and success, crowning her “one of the most accomplished Ghawazee in Egypt”, these memoirs along with the rest of Safiyya’s biography never really talked about who she was as a person, making it hard to get to know her.

Safiyya was considered a pioneer in the belly dancing industry, but her success and influence in the field was often overshadowed by Kuchuk Hanem, another belly dancer who rose to fame following Safiyya’s retirement.

Egypt allowed women from different parts of the world to explore belly dancing by providing them with a larger audience. Sadly, some accounts might lack accuracy because of the orientalist view that many European travelers had on the Egyptian society.

Comments (2)

[…] عشر مع النساء الغجريات اللاتي كان يطلق عليهن “الغوازي(“دخيل”) لأنهم غزا مهنة الراقص وقاموا بحركات غير […]

[…] dance appeared at the start of the 19th century with Gypsy girls who had been referred to as “ghawazi” (“intruders”) as a result of they invaded the dance occupation and made actions that had […]