Most women’s rights defenders in Egypt aren’t quite preoccupied with the alarmingly low number of statues depicting women in the country. Understandably, the issue pales in comparison with more pressing agenda items, like the many forms of de jure and de facto discrimination against women—from legal marital rape and inheritance inequality, to rampant FGM and sexual harassment.

Yet the absence of the female from our public squares and perpetually bustling streets is indicative of a sexist mentality that places far more value on honoring and recognizing men’s achievements than it does women’s.

Public statues and sculptures are a reflection of a nation’s history and identity, fully woven into the fabric of our everyday lives. They are the landmarks that guide our travels through our great metropolis. Once used to cement the status of political figures, such as members of the Muhammed Ali dynasty from the 19th to the mid-20th century, public statues now shape cultural and social perceptions of greatness worthy of commemoration and iconic imagery. And it is usually male figures that dominate this aspect of public life, signaling to the unsuspecting eye the superiority of men.

Things aren’t much better for women elsewhere in that regard. All over the world, men enjoy more representation, with statues of male figures far outnumbering those of women. Among the countless statues scattered across New York City, only five depict women. Many aren’t even named after the women they depict, such as The Statue of Liberty, which was originally inspired by an Egyptian woman holding up a lamp, dressed in the loose fitting garment of a fellaha (peasant).

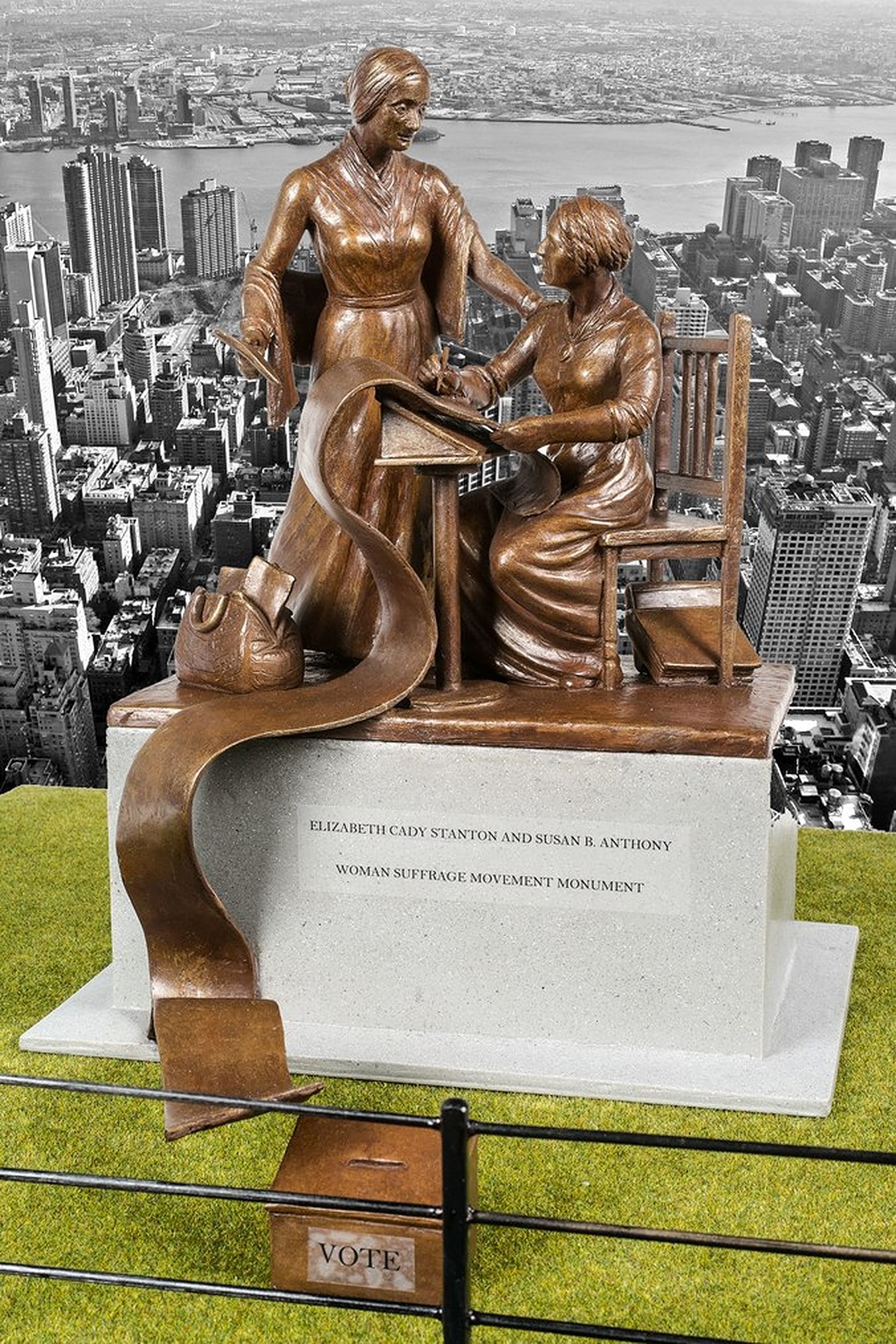

To combat this, a number of campaigns were launched to change that reality. One is #MonumentalWomen, which has recently won approval from New York’s Parks Department to build statues honoring women’s right pioneers Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton in Central Park. The iconic urban park only features fictional female statues on its grounds.

Another notable campaign is inVISIBLEwomen in the UK, which advocates for more public statues of women, arguing that “female figures are largely semi-clad, often reclining, and typically depict a maternal, saintly or sexualized image of womanhood, rather than worldly achievements.”

On March 7th, 2017, one day before International Women’s Day, Kristen Visbal’s Fearless Girl was initially installed facing the much older Charging Bull. Visbal’s bronze structure became an instant global sensation, earning a permanent place in Manhattan’s Financial District. “This statue has touched hearts across the world with its symbolism of the resiliency of women,” Democratic congresswoman Carolyn Maloney said in a statement.

A MAN’S WORLD IN EGYPT?

In Egypt, few women have been honored with such colossal monuments, such as Umm Kulthum, who is indisputably recognized as the Arab world’s greatest recording artist. With a career that spanned three decades, Umm Kulthum has more than earned the bronze statue immortalizing her across the street from the Umm Kulthum Museum.

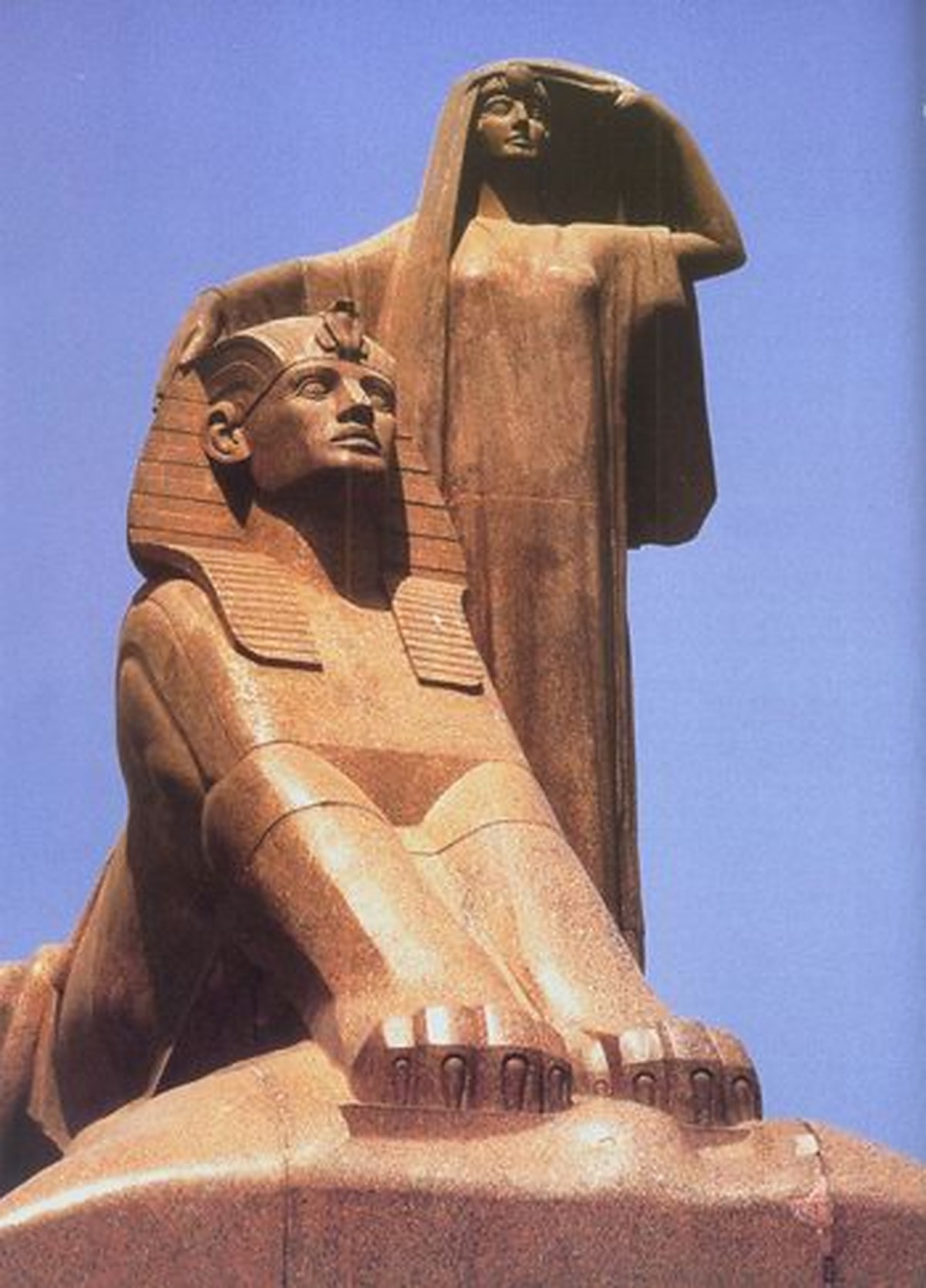

There is also the illustrious Nahdet Masr statue (Rising Egypt), which depicts a peasant woman standing next to the Sphinx to symbolize Egypt’s national aspirations during the struggle for independence from British occupation.

However, while the peasant woman seems to be symbolize emancipation, the full statue seems to co-opt her identity for the bigger purpose of nationalism. With no name, no history, and no background, the woman stands as a lifeless figure rather than a human being that relates and directly speaks to the onlooker, the way Umm Kulthum’s statue does. At best, the sculptures almost renders the woman invisible and incidental.

Another example of this kind of erasure and appropriation can be seen in the statue of Mustafa Kamil Pasha by Leopold Savine, which shows Kamil, a nationalist activist, with one hand on the head of a sphinx while a peasant woman below them is seen listening to his chants of freedom.

According to Lesley Lababidi in her book Cairo’s Street Stories, it was in 1872 when Ismail Pasha, the khedive of Egypt at the time, decided to adopt the European tradition of installing statues of heroic figures in public displays as a symbol of the continuing authority of the Muhammed Ali dynasty. One example being the Ibrahim Pasha sculpture, which stands at the Opera Square in Cairo, after Khedive Ismail asked French sculptor Charles Coedier to build a statue commemorating his father.

The tradition continued on in the 20th century when Egyptian sculptor Mahmoud Mokhtar began to pay tribute to several other political figures, producing the statue of Saad Zaghloul, located on the Qasr El-Nile Bridge. Out of all the statues mentioned in Lababidi’s book, however, only Umm Kalthoum stood out as a pioneering female figure in modern Egypt, next to men like Muhammad Farid, Talaat Harb, Ahmed Maher, Muhammed Abd El Wahab and many others.

This is unfortunate considering the number of notable and successful women who are never held in such high regard or afforded the same iconic status for their achievements, such as world-renowned Egyptian nuclear scientist Sameera Moussa, prominent Egyptian feminists such as Huda Shaarawi, Doria Shafik, and Dr. Nawal El Saadawi, and politicians like Hikmat Abu Zayd, the first female cabinet minister in Egyptian history, appointed in 1962.

Politics has always needed art to survive and grow. And just as politicians have used sculpture to bring life to their past achievements and authority, so too should Egyptian women make their marks on our streets. Egypt’s feminist movement deserves to be honored and recognized, and the longtime struggles and successes of its pioneering women merit a more visible presence in our streets.

Comment (1)

[…] SOURCE: EGYPTIAN STREETS […]