Over the past five years, the narrative has slowly shifted on Syria. Spring soon turned to winter as many countries across the Middle East and North Africa slipped back into their chains and the discourse surrounding the crisis in Syria quickly turned to fear-mongering and gabfests about the ‘collective good’.

Along came a new generation of Syrian filmmakers determined to carry the voices of their fallen countrymen and women out into the world and put Syrian voices in their rightful place: at the head of the table. It is largely thanks to these filmmakers that the war in Syria is documented through unembellished firsthand accounts and stories whose endings aren’t open to interpretation.

They are filmmakers who offer the world no absolution and don’t care very much for self-flagellation or savior complexes.

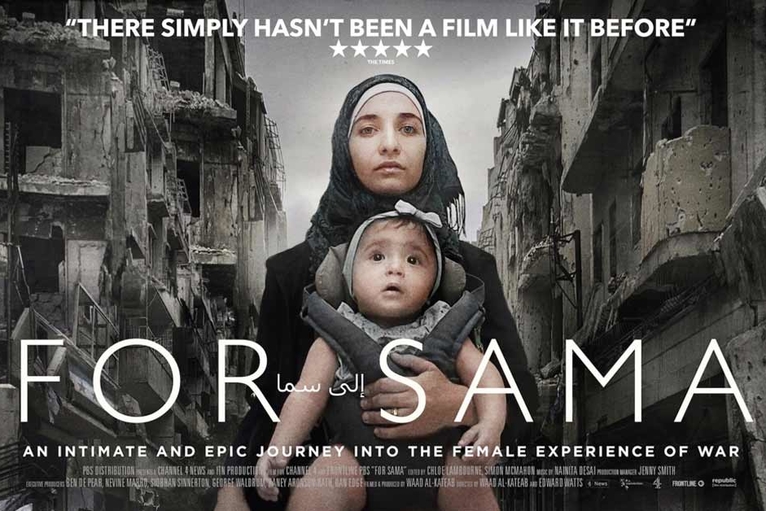

For Sama (2019)

This Academy Award-nominated documentary feature offers a glimpse into the female experience during Syria’s rebellion. For Sama started as an intimate project by Syrian journalist Waad Al Kataeb in which she retells Syria’s struggle for democracy, her part in it and her journey as she navigates these harsh realities as a woman and as a pro-democracy activist.

The documentary is a filmed message by Waad to her daughter Sama. As Russia and the Assad regime’s military offensive in Aleppo intensifies, Waad fears for hers and her husband’s longevity and starts working on the film to leave to her daughter in case they don’t make it.

It follows her story as an activist, as a woman in love and as a mother. Waad tells her daughter how she joined Syria’s protest movement as a student activist at the University of Aleppo in 2012, how she met, fell in love and eventually married her father, Hamza Al Kataeb.

Waad explains to her daughter why she and her husband, then a doctor at Aleppo’s last rebel-held hospital, doggedly refused to flee the city, even during the darkest moments of the Battle of Aleppo, and why they eventually did.

It is an emotionally overwhelming watch that attempts to piece together a generational narrative about Syria. Through Hamza and Waad’s story, the film offers viewers a glimpse into the trauma of parenthood in a war-torn city as the young couple shoulders the responsibility of leaving the world a better place for their daughter and her generation.

Directed by Waad and Edward Watts, For Sama made history earlier this year when it became the only documentary feature to ever be nominated for four BAFTA award categories.

Silvered Water, Syria Self-Portrait (2014)

Ma’a Al Fidda (Silvered Water, Syria Self-Portrait) is one hour and 30 minutes of raw, visceral scenes from life in the war-torn country.

Unbearable to watch at times, yet utterly engrossing, Silvered Water features videos from over 1,001 Syrians, according to Paris-based Syrian filmmaker Ossama Mohammad who co-directed the film with Kurdish activist Wiam Bedirxan.

The two began working on the project after Bedirxan, who was based in Homs at the time, sought Mohammad’s help to document life in the besieged city.

The film collates Bedirxan’s reels with amateur footage taken by Syrian activists, social media users and others who documented the conflict’s most surreal moments on their personal devices. The two filmmakers render a masterful and relentless audiovisual rhetoric of life in Syria.

Silvered Water is structurally hectic, casually macabre, and even rage-inducing. It captures Mohammad’s survivor’s guilt and the desperation and abject misery one might imagine of the conditions in Syria and then some.

One such raw footage—believed to have been filmed by Syrian soldiers loyal to Bashar Al Assad—shows a teenage boy being humiliated, tortured and sodomized, other scenes depict the streets running with blood and murdered children in coffins.

It is devastatingly damning, triggering and exhausting to watch, but it is an honest testimony of the war in Syria that will haunt humanity for generations to come.

Last Men in Aleppo (2017)

Another groundbreaking film, Last Men in Aleppo made history when it became the first Syrian-directed documentary feature to be nominated for an Oscar.

Directed by critically-acclaimed Syrian filmmaker Feras Fayyad, Last Men in Aleppo follows three rescue workers, Khaled Omar Harrah, Subhi Al Hussein and Mahmoud Al Hattar, as they struggle to keep the city alive in the midst of Bashar Al Assad and Russia’s brutal and indiscriminate attacks during the Battle of Aleppo. According to Fayyad, Aleppo residents were bombed 15 to 25 times a day.

The three men are among the founders of the White Helmets (the Syrian Civil Defense), a group of first-responders founded in 2013 who pull bodies out of the heaps of rubble in the wake of each attack.

Throughout the documentary, we see the rescuers grappling with the desperate and overwhelming conditions in Aleppo and wrestling with the decision of whether or not to leave the city.

Torn between their love for their communities, their sense of duty, their survival guilt, and their all-too-human will to live, the documentary depicts the moral turmoil of heroism, altruism, and self-sacrifice. It is one of the most ambitious films of its genre because it masterfully and emotively deconstructs the moral oversimplifications about heroism in public imagination.

The Cave (2019)

Another Oscar contender, The Cave is Feras Fayyad’s feminist followup to Last Men in Aleppo. It follows the story of Dr. Amani Ballour, the first woman to ever head a hospital in Syria.

The documentary portrays the unique struggles women face in Syria’s revolutionary landscape and the multiple fronts they must fight on.

In The Cave, Dr. Ballour fights heroically to fulfill her duty as a medical professional amid one of the worst humanitarian crises of our time, while also battling sexist and misogynistic attitudes that seek to undermine her work and contributions to her community.

Dr. Ballour runs a makeshift subterranean hospital in Ghouta, a city recently retaken by Bashar Al Assad’s forces with help from Russia. At the time of filming, Ghouta, like Aleppo before it, suffered through a protracted siege and innumerable bombings that left countless dead and injured.

Throughout the documentary, we see the hospital’s staff and a group of female doctors, braving the incessant shelling to save lives using the limited resources at their disposal.

The Cave depicts the desperation of Syria’s last doctors and rescuers, and recognizes the unique challenges faced by women in the country’s humanitarian and revolutionary spaces.

The film presents a necessary, yet nuanced critique of Syria’s ongoing revolution as it dovetails with the larger conversation about women’s place in post-Arab Spring societies and their overlooked contributions to the regional protest movement and pro-democracy activism.

Of Fathers and Sons (2017)

Directed by Syrian Kurdish filmmaker Talal Derki, this Oscar-nominated documentary feature offers a glimpse into the life of an Islamist family in a village controlled by Al Nusra Front, a salafist jihadi militant group.

To shoot the documentary, Derki posed as a photojournalist sympathetic to the salafist jihadi opposition movement. The film follows the Osama family whose patriarch, Abu Osama, is one of the founders of the militant Islamist group.

The film delves into the family’s daily life and unearths predictable patterns—the father pulls his children out of school due to his ideological views on mixed-gender education, for example, but it also sheds light on the broader narrative, culture and philosophies of islamism and jihadism.

One such revelation was Abu Osama’s apocalyptic prophecy that the war in Syria will end with the advent of the Mahdi after a holy war between a newfound Caliphate and the Christian world.

Overall, the film explores the depth of the family’s convictions, which are not only passed down from one generation to the next through lore and tales of martyrdom, but also using forced indoctrination.

This becomes evident when Abu Osama sends his two young sons Ayman and Osama to a combat training camp in the hope that they will grow up to be Islamist militants in their turn.

The film leaves viewers uncomfortable and even despondent, but it is also an intelligent commentary on the rise of jihadism and terrorism in Syria’s anti-Assad movement. It seeks to not only understand what drives many into such an ideology in times of political upheaval, but also to examine how such a fate can, at times, appear preordained for many children in Syria today.

Comments (0)