At a time when the state is committed to fighting a global pandemic, a hidden pandemic continues to rot Egypt from the inside: domestic violence.

The magnitude of the problem is far larger than what the government and political officials conceive. It demands more than just short-term responses or funding to emergency and support services, as U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres called for, but a forward-looking strategy that aims to redefine the way states should look at the domestic sphere.

Globally, there has been a surge in cases of domestic violence. In France, the police reported an increase of about 30 percent in domestic violence, and in Spain, the emergency number saw an 18 percent increase in just the first two weeks. Reasons for this have often been linked the ‘stay at home’ measures that have been imposed and the added stress that comes from loss of jobs or income.

However, even before the pandemic, domestic violence has been every country’s shadow terrorism. It is an issue that is rooted more deeply in how societies are structured along gender and power lines and how the household structure is perceived. Women’s role in the domestic sphere, for instance, has been constructed and defined by their husbands and children. For many women, it is their sole source of identity, putting them at greater risks of abuse and vulnerability.

What this global pandemic has shown is just how many can be left behind feeling more powerless in their own household structure. Excessive dependency on this traditional household structure to play the main role in providing support and survival for its members can risk and waste more lives than what official numbers reveal.

How can we define domestic violence?

According to the Egyptian constitution of 2014, violence against women is mentioned in Article 11 “…The State shall protect women against all forms of violence and ensure enabling women to strike a balance between family duties and work requirements…”

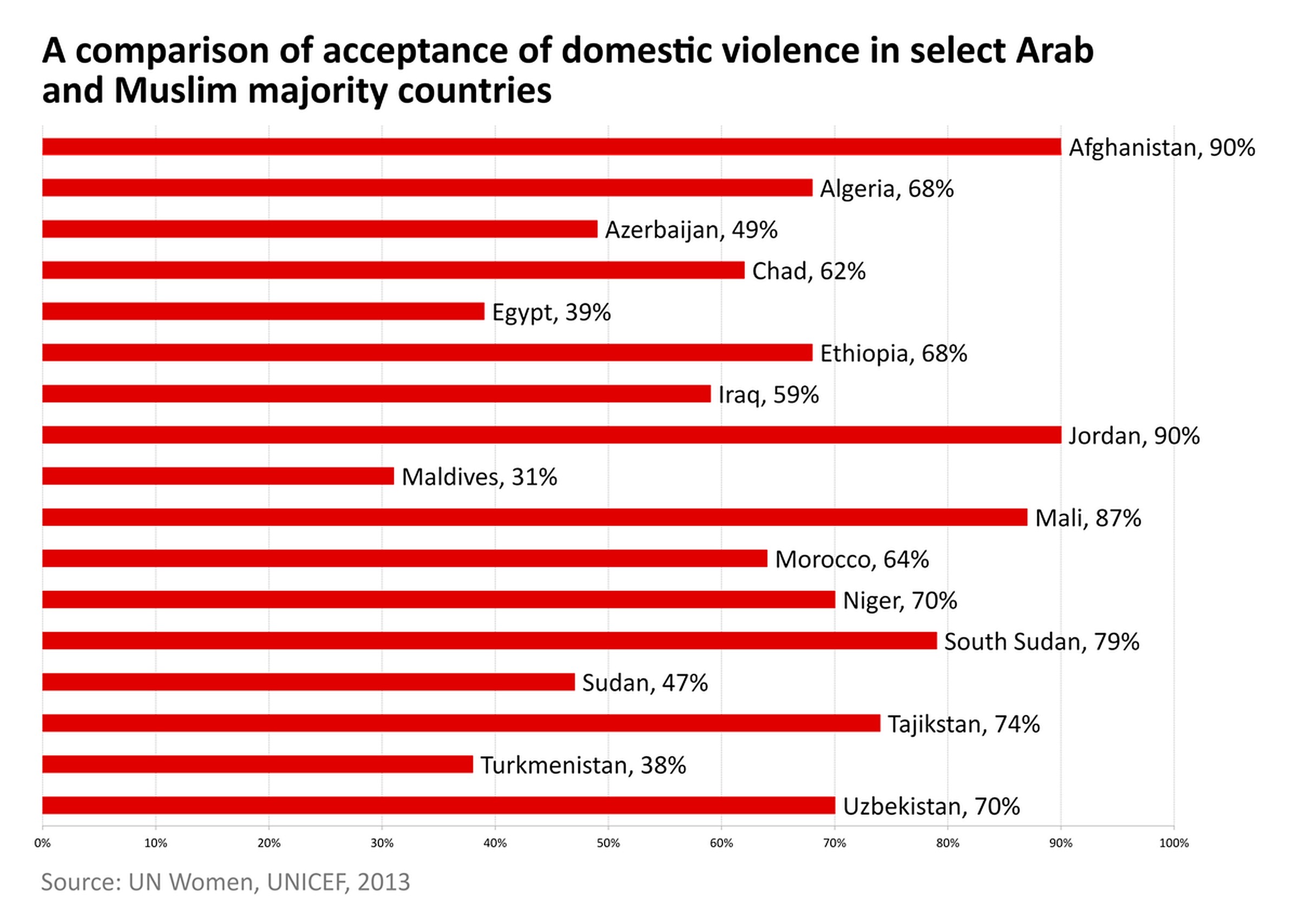

However, domestic violence is still tolerated by many in Egypt. According to the UNDP Gender and Justice report on Egypt, there is no law that explicitly refers to domestic violence. While some domestic violence offences may be punishable under the Penal Code and Law No. 6 of 1998, it is only if it is considered to be beyond “the accepted limits of discipline decided by the judge” and “if the injuries are apparent” when filing the complaint at the police station.

Article 60, for instance, can still be used by the perpetrator to be pardoned if he acted in “good faith”, which is regarded as “the husband’s right to discipline his wife.”

For that reason, it is important that the concept ‘domestic violence’ encompass the different interpretations coming from the legal context, policy context, service provision and the community itself. A more detailed definition is provided by the UNICEF, which defines it as “violence perpetrated by intimate partners and other family members” and is manifested through various forms: physical abuse, traditional harmful practices (such as female genital mutilation), sexual abuse, psychological abuse, and economic abuse.

It is also significant to note that while the term ‘domestic’ is meant to refer to the intimate relationship between the victim and the perpetuator, it can also include violence that is practiced after this relationship ends, such as ex-partners. This is vital as abusers can often weaponize the end of a relationship and use child contact as way to continue perpetuating abuse against their former partner.

Divorced from justice

With court trials suspended across the country, many have been abused relentlessly and deprived of their rights, fueling perpetrators to abuse their victims further. Since the beginning of the shutdown measures last month, Gender and Legal Expert House (GELEH) represented by senior lawyer Nehad Aboul Komsan, who is also the chairwoman of the Egyptian Centre for Women’s Rights, has seen a surge in family conflict and cases of violence, representing 43 percent of the total number of 1146 cases received, with over 70 percent of the complaints received by women. Another study revealed a 33% increase in family problems, 19% increase in violence between family members, and 11% of wives subjected to violence from their husbands.

“I endured everything for my children,” Salma* says, “He has been humiliating me verbally and beating me constantly, and a few days ago he beat me until I got an open head injury, and now he is telling me to get out of the house and that he would divorce me. But I don’t know where to go, there are no courts currently operating to get me my right from him.”

Suspension of courts has also hindered the implementation of previous rulings that were in favour of women’s rights, such as cases of inheritance, alimony, marital residence, and others, which further exacerbates violence against women. Hagar*, for instance, depends on her ex-husband’s alimony for support, though he refrained from paying them and asked her, in a threatening tone, to go “hit her head in courts” – an Egyptian expression to imply that she would not obtain her right. “How can family courts shut down? This was the only way I could’ve gotten my right, but now I have no other way,” Hagar* pleads in a message to the Gender and Legal Expert House.

Dependence on their husbands and children is a factor that is often mentioned in most of these stories, revealing the unequal nature of the relationship that characterizes abusive households, and the need to tackle this problem from its roots.

Lawyers are also left helpless with the delay and suspension of court sessions. “We ask them to report it to the police department along with a medical report, which is presented to the public prosecution and then sent to the court to determine a session, but unfortunately all court sessions have been suspended, so the matter is taking more time and we do not know what will happen,” lawyer Ahmed Eiz tells Egyptian Streets, “This delay puts a lot of added psychological pressure because there’s a lot of uncertainty.”

In other cases, where the woman is unable to bear the costs of cases and attorney’s fees, they are advised to go to the National Council for Women, which hears complaints through the hotline (15115) and the women’s complaints office.

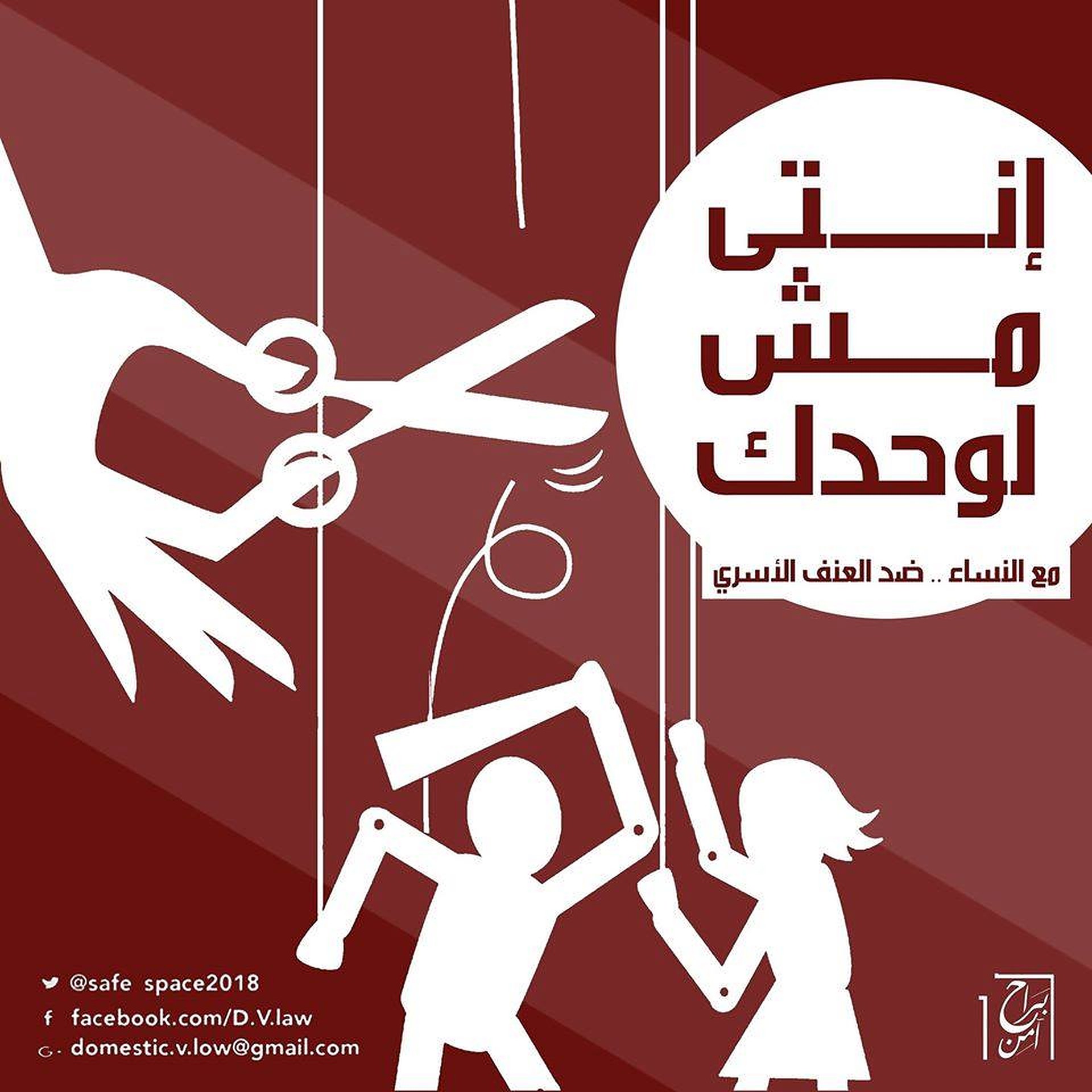

To respond to the needs of these women, GELEH has been providing legal consultations through multiple channels, whether hotline, on their website ‘Ask Your Online Lawyer’, or through their Facebook messages.

The Egyptian Centre for Women’s Rights also launched the online campaign, “Coronavirus Is Not An Excuse For Violence,” in which it shares several tips on how to ease tension inside households, spot an abuser, and how to protect one’s self from an abuser. To support them psychologically, Nehad Aboul Komsan has been posting daily short videos that combines messages of awareness and simplicity, addressing various topics such as gender roles, family and work balance, and how women should take care of their mental and psychological health.

Egypt’s Ministry of Social Solidarity also announced intensification of measures for children in foster homes and women shelters, as well as readiness to any potential cases of violence against women.

Pushing forward

The question remains to be asked: how can the wheels of justice keep turning during the COVID-19 and even beyond?

Victims of domestic violence need to be heard. The fundamental goal should be to ensure that victims are heard and are not overlooked due to a limited definition of domestic violence.

The need for radical actions and policies that take in consideration the deep-rooted cultural, social and economic conditions that brings rise to domestic violence cannot be underestimated. It should reduce the dependency on the household structure to provide the main source of support by increasing nation-wide places of child and elder care, with a primary aim to reduce women’s confinement and vulnerability in the domestic sphere.

Legislations should include a detailed and comprehensive definition of domestic violence, which stresses on coercive control that characterizes abusive relationships. The judicial landscape needs to also rethink ways of how to adapt to crises, respond to victims and prosecute perpetrators.

If the issue is not dealt with much more urgency, it can further add to the economic woes of the COVID-19 crisis. The cost of violence against women globally can reach around US$1.5 trillion, and in Egypt, around EGP 2.17 billion annually. These numbers will most definitely continue to increase during the pandemic, and create serious aftermaths later on.

*Names were changed to protect anonymity.

Comments (6)

[…] that were already deep rooted in societies have become ever more apparent, with a spike in domestic violence, sexual harassment and particularly online sexual exploitation and abuse of women and girls under […]

[…] Egypt’s Hidden Pandemic: Domestic Violence On The Rise During COVID-19 […]