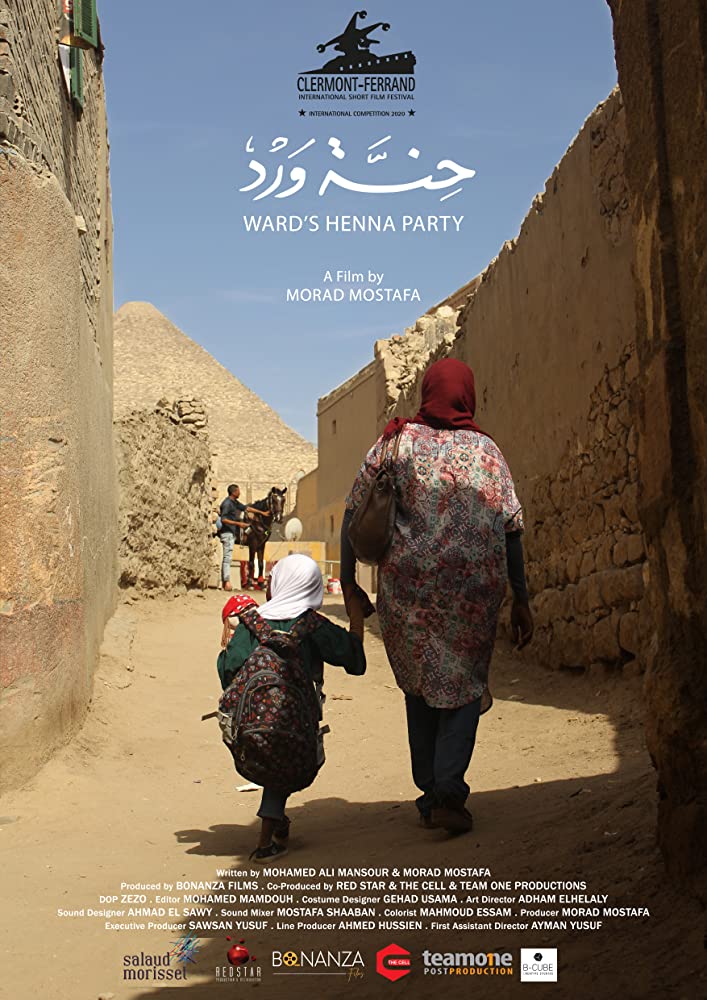

As she holds her young daughter’s hand firmly, Halima, a Sudanese henna painter living in Egypt, walks towards an Egyptian household to prepare a bride for her wedding. In a room full of cheering, dancing and chatter, she seems uncomfortably tense and silent as she waits to find a safe spot to work.

“The henna lady is here,” one woman says while she clears some space for Halima to sit down,”come on girls, leave the room so that the henna lady does her job.”

Without recognizing her presence in the room, the girls continue to tease one another as they clean out the mess in the room. Halima, on the other hand, stands watching.

Shot inside just one Egyptian household, the short film ‘Henet Ward’ honestly captures the struggles that refugees in Egypt experience in very private and intimate settings. It follows their footsteps throughout their journey, presenting a very raw and real visual experience that touches on the subtle and hidden undertones of racism and bullying.

Directed by Morad Mostafa, the film was recently announced as the only Egyptian film selected for the Palm Springs International ShortFest, as well as being picked among the Oscar qualifying awards, according to IndieWire.

Egyptian Streets spoke with Egyptian director Morad Mostafa on his inspiration and why this film is so particularly relevant today.

What is your main inspiration behind directing this film?

I wanted to place this character in a very simple Egyptian house, specifically inside a very secret and private world such as preparing a bride for her wedding, to capture the little details that happen during this event and the subtle tensions between the characters.

I wanted to highlight the realities of racism in Egyptian society, and also the increasing signs of anger, bullying and conflict, and how small conflicts may turn into major fights.

What is the main message you wanted to send across?

I wanted to look at the ordinary lives of simple people, and the hostility that they have among one another. But also more specifically on the lives of refugees in general and the Sudanese in particular.

I also wanted to present the incidents of racism and bullying between Egyptians and the Sudanese in popular neighborhoods through the eyes of Halima, and the sudden dramatic escalation that occurs. The film has neither rich nor poor; it is violence and tension between two similar classes, and how bullying and racism happens in these circumstances.

What was the process of directing like and how was it different from other films?

Working on this film was very different for me because I wanted to make a film with real people, so the casting process wasn’t very easy. From the first moment while writing this project I knew that I wanted real people who are not acting professionals, because they would be much closer in resemblance to the characters.

I wanted their feelings to be very spontaneous in front of the camera, not under control. This made the general atmosphere of the film closer to a documentary style, but in the form of a narrative.

Casting the Sudanese woman, of course, was difficult because I was looking for a Sudanese woman in her early forties with a young daughter, and works as a henna painter in Egypt. All this was very difficult. But, frankly, it was an enjoyable experience from the moment of casting her until the training process.

The film took about 6 months, from writing until post production, finishing last year. Specifically, we started writing in March of last year, but it is hard to make a film in Egypt these days due to the current economic conditions and the state of the industry. These days any director has to have somewhere to begin, and I wanted to begin this moment with Henet Ward. I decided to produce this film with my own money and not to depend on funds from any institution, as they consume time.

We filmed somewhere around mid-July. After the production stage, other companies joined in to help me, like Red Star Films, the Cell and Team One Productions. Because we had limited resources, we needed to spend the money on the basic and important requirements like locations and equipment and permits, and what helped me navigate all these difficulties was the crew that believed in the film and in me.

Most of the props were from my house and from my crew members’ houses or the residents of the area, so I want to thank them all greatly for this help.

Why do you think this film is relevant and deserves more attention today?

The film is considered to be a metaphor for Egypt today, specifically for post-revolution society.

Halima’s issue is also a global issue that exists in any country or society. But to mention Egypt, I will say that there is definitely existing racism between Egyptians and African refugees in particular, and this increased in post revolution society.

On the other hand, the situation of the Sudanese refugees in Egypt is also somewhat similar to the simple lives of Egyptians themselves, like Basma and her family. All have similar dreams and ambitions, and simple life needs like food, sleep, and getting married.

And this is what I’m most concerned about. As of 2020, the numbers of refugees in Egypt reaches around 40,000 according to UN Committee for Refugees. They came to Egypt to find a job and escape war and oppression. They don’t have the best situation in Egypt or other any country, and so I wanted to capture these struggles through camera.

Comments (6)

[…] “I wanted to look at the ordinary lives of simple people, and the hostility that they have among one another. But also more specifically on the lives of refugees in general and the Sudanese in particular,” Mostafa told Egyptian Streets. […]

[…] “I wanted to look at the ordinary lives of simple people, and the hostility that they have among one another. But also more specifically on the lives of refugees in general and the Sudanese in particular,” Mostafa told Egyptian Streets. […]