Egyptian women are engaged in endless battles that surface on all levels of society: From a wave of arrests of young women on TikTok to constant discussion around the dangers of sexual harassment in its various forms, one cannot help but think that to be a woman in Egypt means constantly fighting to survive in a system seemingly designed to break you.

Living in Egypt means realizing that violent behaviour towards women is socially accepted and often justified despite attempts from the government, NGOS and the public to eliminate these attitudes. The majority of the Egyptian population seems keen on maintaining the overpowering patriarchal structure of society as a whole. The factors that make up this system cannot be addressed in isolation, and their interconnectedness needs to be explored.

As per a traditional definition, a patriarchal society is one where men hold power over women. Accordingly, it is impossible to deny Egypt’s patriarchal nature because it taints every aspect of Egyptian life, from educational, religious, and judicial institutions, all the way to families and households.

In a study conducted by UN Women in 2017, 86.8 percent of Egyptian men and 76.7 percent of women stated that a woman’s primary role in society is at home cooking and caring for the family, and according to the 2017 study conducted just three years ago, over 90 percent of Egyptian men and 58 percent of women believe that men should have the final say when it comes to major household decisions.

However, bringing about social change and transitioning to a more egalitarian society away from patriarchy is a complex and indirect process. In order to understand and eradicate social disparities rooted in gender in Egypt, we must understand how misogyny, a general dislike of women, or an ingrained prejudice against women, intersects with other forms of oppression.

While patriarchy refers to a system of society, misogyny itself refers to the attitudes perpetuated by this system.

When facing the realities of gender-based discrimination and violence in Egypt, it becomes clear that there is no single factor or culprit that threatens female existence, but rather a combination of actors that exude and uphold sexually aggressive and controlling narratives at all levels of society. More than controlling women, these legislative, religious, and social efforts perpetuate a culture of female silence and male complacency, which only serves to solidify and uphold misogynistic attitudes.

Where Poverty, Access to Education and Patriarchy Meet

A study carried out by UN Women in 2013 revealed that 99 percent of Egyptian women have experienced some form of sexual harassment or assault. Although all women in Egypt can attest to a general lack of safety within the country, gender dicrimination takes many other forms across different social levels.

One clear example of discrimination and violence is that girls in Egypt have less access to education than boys. Instead, many are pulled out of school before completing their secondary education or are denied higher education. Some young girls, victims of more radical beliefs in their communities, do not even reach advanced grades in schools and are married off as children. As such, there are more illiterate women, standing at 64 percent of the illiterate population in the country, than men. But how can distinctions be made between different individuals’ experiences?

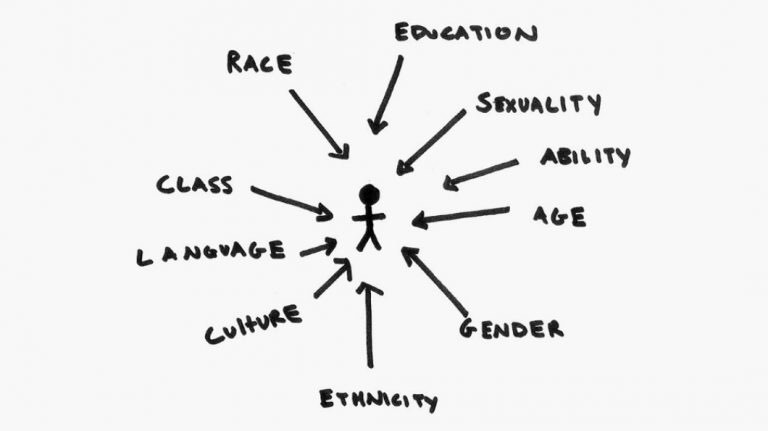

Intersectionality recognizes that one illiterate girl with no access to education is likely to be the same girl subjected to the trauma of female genital mutilation (FGM) then later married as a child bride. These three different characteristics of oppression are enabled by negligent schools, corrupt medical practitioners, lazy law enforcement, and dangerous family values, and they can easily meet in the life of one young girl.

Whether a young girl or a woman is being oppressed in cosmopolitan Cairo or rural Upper Egypt, it is crucial to adopt an intersectional lens to see how different forms of oppression can overlap to create one person’s struggle. It identifies the various unique outcomes of considering different types of inequality alongside gender, such as poverty, literacy, or physical ability, and others.

Varying Degrees of Privilege, Varying Degrees of Suffering

Issues such as FGM, child marriage, honour killings, domestic violence, and sexual violence all disproportionately affect women and girls. Still, they all stem from the belief of female honour, and the imposition of modesty and shame on women – what Egyptian journalist Mona El-Tahawy refers to as ‘purity and modesty culture’.

The unmotivated enforcement and obscurity of Egyptian laws regarding women’s rights, along with the cultural and religious obsession with female purity and honour, and the significant lack of economic access for women are all factors that shape the female experience in Egypt. These behaviours are enabled by various institutions that interact to form social structures, whether it’s through the media’s shallow representation of women, gender-biased education, or social values that seek to destroy female autonomy.

The problems that feminism aims to tackle are upheld by different social, economic, political, and legal contexts, and when gender discrimination intersects with poverty and its effects, different tools of female oppression come to light. It becomes clear that social attitudes towards class affect specific types of women on the economic spectrum, women with different levels of education. It becomes clear that within varying degrees of privilege lie various degrees of suffering.

Kimberlé Crenshaw developed the term ‘intersectionality’ in 1989 when examining the plight of Black women in the US by analysing the intersection of race and gender. The concept represented the acknowledgement that women’s struggle with racism is distinct from men’s. It highlighted the experience of being a Black woman in America and helped map out the different aggressions faced by different women, for being women as well as Black. It also identified and validated different identities within a marginalised group of people.

Breaking Down the Struggle Through Intersectionality

Intersectionality is a great lens through which to appraise the intricate nature of sexism in a country like Egypt, where violence against women is a shapeshifting tool embedded within our complex social hierarchies, used by institutions who pave the way for different forms of gender-based violence and control. For example, in 2005 security forces were accused of using sexual harassment as a weapon agaisnt female protesters, to discourage their political involvement. Women were targeted, sexually harassed, and groped by mobs of men, with videos circulating of authorities idly watching from the sidelines.

The various barriers women face are caused by the prevalence of gender-biased attitudes and norms adopted throughout society, becoming a defining factor at every stage of a woman’s life. It’s visible in the medical sector, where women are subject to various procedures and examinations with coercion or no consent – like Samira Ibrahim, who was subjected to a virginity test after being beaten and strip searched by soldiers at a Tahrir Square sit-in in 2011; or in religious institutions who may advocate victim blaming with candy wrapper analogies.

A Coptic woman in Minya could be facing a combination of religious and economic barriers that would force her to stay in an abusive marriage, and another woman’s life could be at risk from her own family threatening to kill her for honour.

The institutions involved in a woman’s life protect predators, shame victims, and if you are neither a predator nor a woman, ensure complacency. A woman in Egypt could be discriminated against in the workplace, regularly harassed by strangers on the street, medically violated, abused at home, or a combination of those things. By analysing the interrelatedness of gender and other inequalities, and how they each transform the gender experience; it becomes obvious that to be a woman or a girl in this country can birth different meanings for different women and girls.

The uniqueness of each situation makes an intersectional approach to feminism crucial to understanding gender aggression and how it is inflicted. It becomes clear that 17 percent of girls getting married before the age of 18 is caused by a combination of oppression rooted in religious practice, education, and economic realities. Intersectionality also helps to break down why 90 percent of women have undergone an FGM procedure when the practice was criminalised four years ago, and why it killed a 12 year-old girl this February. It illustrates how this is a result of combined, continuous, and most importantly collaborative institutional behaviours that cannot be tackled in isolation. It is how we begin to understand the breeding ground for a culture that is violent towards its women.

*The opinions and ideas expressed in this article do not reflect the views of Egyptian Streets’ editorial team. To submit an opinion article, please email [email protected].

Comment (1)

[…] Privilege and Suffering: Intersectionality as a Tool to Understand Women’s Struggles in Egypt […]