“Stories are what made people survive so far in history.”

This is what brought Mahmoud El Far, Egyptian engineer-turned-screenwriter, to the TV and Film industry.

“From gathering around campfires to reading books, seeing a play, and watching Netflix. Even [in] religions, people are mostly compelled by the stories they found in the Quran or the Bible. Stories give so much meaning to life, and TV and film let you share these meanings with other people,” El Far said.

Egypt has long had one of the strongest film industries in the region, with many of its classics being regional fan favorites for Arabic speakers. In 2013, the Dubai Film Festival curated a list of the Top 100 Arabic Films, 52 of which were Egyptian classics.

While Egypt’s Film and TV industry has historical roots to stand on, El Far, who has worked on TV sketch comedies, online shows, cartoons, adult animations and films, believes it should be far stronger than it is currently is.

“It should be [like] Hollywood or even better. But you can never compare Egypt to Hollywood. I believe that it’s not our fault that our content isn’t as good as it should be,” he said.

Egypt has one official film school, while there are hundreds in the U.S. and the U.K. and thousands around the world, he added, so there are fewer opportunities to pursue the profession.

“They have the money to do so. They colonized us and so many other non-white countries, and in a way, they still have an influence on third world countries that doesn’t let them unlock their full potential. They have kids making iPhones and Nike shoes in Africa and Asia so that white people could have cheaper phones and cheaper shoes,” he added.

El Far says that most Egyptian writers he meets are actually former engineers or doctors, as there are not many people in the country who study filmmaking or screenwriting at a university level.

He adds, though, that despite academic expertise and traditional education, almost any writing could become better with practice.

“Writing takes time and multiple drafts. And that requires more time and more money and we usually don’t get either of those, especially in Ramadan seasons where it’s always rushed,” he said.

El Far started pursuing the profession of screenwriting when he found an online ad asking for writers to join an Arabic version of a well-known American show.

“I applied with a couple of sketches and it turns out it was SNL Bil Araby,” he said.

Since he had not studied film at any point, he relied on reading books about writing and watching video essays to develop his craft. He’s currently pursuing a Dramatic Writing Masters of Fine Arts at New York University, but he always used to feel “imposter syndrome” calling himself a writer before formally studying it.

“Whenever I’m stuck I always ask myself, am I stuck because I’m having a usual writer’s block or is that just because I’m not really a writer? The words “artist” and “writer” feel like heavy and somehow pretentious words,” El Far said.

Imposter syndrome is a common experience, especially for those who work in industries where the path of entrance is unique for each person, rather than more traditional career paths.

“In time, you learn how to appreciate and enjoy the good moments and handle the bad ones like a working professional,” he added.

How Independent Can Independent Filmmakers be?

A fellow engineer-turned-writer is Abdallah Dnewar, who took several film courses during his time as an engineer and practiced both professions concurrently for a long time.

“Filmmaking can’t be a side job, but at the same time as an independent filmmaker, you don’t make much money. So, if I want to write a series or a film, that takes a long time; to write a story, characters, a backstory. It’s a very long process without payment in return. So to have the free time to do all this, to spend a year or more writing a film or series, how will I live? That’s the dilemma we live in,” Dnewar shared with Egyptian Streets.

He currently works as a freelancer in the video and filmmaking fields on more commercial projects.

“Of course it’s not what I wanted to do, but it’s so I can work on my writing projects in my free time,” he added.

Dnewar aims to add more diversity to the stories told in Egyptian media, bringing dimension to flat characters and adding value to the storytelling that tends to be repetitive or recycled. Part of the reason for that, he says, is because of there being many regulations in place for independent filmmakers in Egypt who aren’t graduates of the High Cinema Institute.

“We’re treated as if we don’t exist here, except for a few independent filmmaker festivals here and abroad,” he added.

From Self-Taught to Traditional Training

Ali Nasser is a screenwriter and actor who did study Film and Theatre early on at university as minors. He worked as a copywriter in Cairo where he was able to learn about scriptwriting and storytelling, as well as reading books and familiarizing himself with tools like Final Draft by reading scripts for his favorite films that were available online.

After moving to the US to pursue his passion, he is now attending a 2-year acting conservatory at the William Esper Studio in New York while maintaining a day job in advertising, and writing pilot scripts on the side.

“I’ve always been passionate about creating and telling stories. Even as a child playing with action figures, I remember creating these elaborate scenarios and imagining what a conversation between two of my toys would sound like,” Nasser told Egyptian Streets on his initial attraction to storytelling.

He grew to love filmmaking as an art form and specifically gravitated towards dialogue-heavy films from writer-directors like Quentin Tarantino, the Coen Brothers, and Mel Brooks. While he initially was interested in acting, his passion for screenwriting came out of a desire to write pieces for himself as he hardly saw stories in Egyptian media that reflected his comedic sensibilities.

“I knew I wanted to be part of that world (either as an actor or a writer) but I didn’t know my way into the industry in Egypt, so advertising seemed like a logical starting point,” he said.

Nasser observes that the film industry in Egypt is not delivering to its true potential, with movies and shows having recycled stories or plotlines, either from Western media or from previous Egyptian movies and shows that tackled similar topics.

“Many of the comedies are nothing but a series of poorly written jokes strung together by a threadbare plot, and the dramas are convoluted and overblown to the point of exaggeration,” he said.

That pattern is most clearly shown in Ramadan series, he adds, where stories that can be told in 10 episodes get unnecessarily stretched to 30, giving the productions exposition that is in his view useless.

“Many screenplays are being written as star vehicles as opposed to ensemble pieces, where the writing is optimized and catered to the headlining star in a way that amplifies their performance style and real-life persona,” Nasser added.

There is significant potential to explore new and different genres and formats of storytelling, Nasser adds, as he sees Egyptian media being limited to either slapstick comedies or social dramas, and not taking risks in telling non-traditional stories.

“Egypt is a country that is rife with amazing stories, whether it’s from our history, modern-day urban legends, or subcultures that aren’t represented on screen. I don’t feel we’re taking advantage of that because these stories aren’t mainstream or commercial enough for a general audience,” he said.

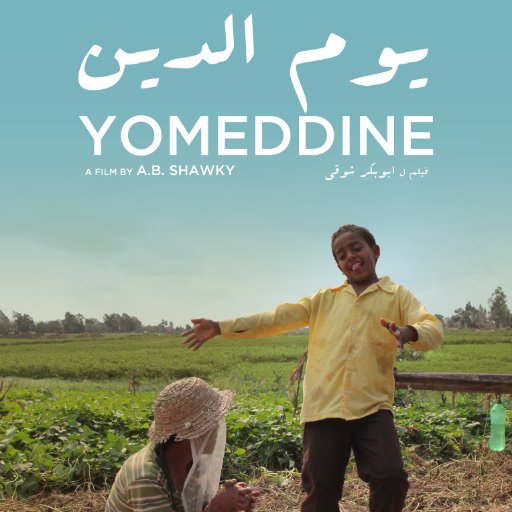

He used the film “Yomeddine” as an example of a film that took a risk in telling a non-traditional story of a community never represented before on screen. The film, directed by Abubakr Shawky, was selected to participate in the 2018 Cannes Film Festival, and compete for the Palme d’Or award. It was also Egypt’s official submission for the 91st Academy Awards.

Dnewar echoed similar statements, stating that a very small number of directors and writers break the theme and the cycle of the same stories and do something new.

“We have a lot of powerful directors here, but we don’t see them often because that’s not what the viewer is looking for. We consume junk films more than films of importance or impact, and we don’t see experimental or art-house films on TV,” Dnewar said.

The Future of Filmmaking in Egypt

Another issue the Egyptian Film and TV industry faces is censorship, which limits the types of stories that filmmakers are able to tell on a public forum. That is considered one of the uncontrollable variables that Egyptian filmmakers have to deal with. Multiple films are banned, or are on a long waitlist to be approved by the censorship board, according to a Cairo Review essay from 2018.

Despite that, there seems to be hope of better quality films from the budding filmmakers.

“In fairness though, the production value has improved tremendously in the last few years – TV shows are becoming more cinematic, and films are becoming more adventurous and experimental,” Nasser said.

He hopes that the onset of streaming services like Netflix or Amazon Prime and their desire to create content that caters to the Egyptian audience will be the shot in the arm needed for the industry to start competing on an international scale.

As opposed to Dnewar and El Far, however, Nasser is currently pursuing the profession as an Egyptian outside Egypt, which can be different in terms of the stories and subject matter that can be explored.

“Once I moved to the US, I became more driven to tell stories from our part of the world to a Western audience. I’m often baffled when I see American shows that tackle topics about Islam or the Arab World but the writers for the show have never even set foot in an Arab country or don’t understand the culture. As evidenced by Ramy Youssef’s success with his show “Ramy”, there has been an evident push from the industry to be inclusive of minority writers and to tell stories that are more diverse in nature,” Nasser shared.

He hopes his stories get to be among them. He has previously written a short film that tackles the experiences of a fish-out-of-water Egyptian immigrant in New York against the backdrop of the Trump presidency.

Nasser advises aspiring screenwriters to take acting classes, specifically ones that focus on improvisation, as the best way to determine the quality of written dialogue is to hear it performed out loud.

“It will also help you step out of your comfort zone, especially when you pitch your script to a studio or producer,” he said.

Despite saying that he does not believe in advising people no matter how successful he gets, he recommends for up-and-coming filmmakers to shed their ego.

“The process of filmmaking isn’t scientific like physics so there are no stable rules you can follow. Filmmaking is based on imagination. And imagination is different from person to person. Someone 10 years younger can write something better than me,” Dnewar said.

Regardless of where they’re based, these Egyptian filmmakers and storytellers have one thing in common: telling authentic stories that mean something to others. While the industry in Egypt is far from perfect, Dnewar, Nasser and El Far have hope in a future full of diverse stories and intriguing performances.

Comments (7)

[…] films are difficult to make, without large budgets and with little support for the arts. Multiple filmmakers have said that they need to take jobs next to creating their films to support themselves financially. […]

[…] films are difficult to make, without large budgets and with little support for the arts. Multiple filmmakers have said that they need to take jobs next to creating their films to support themselves financially. […]